Contents

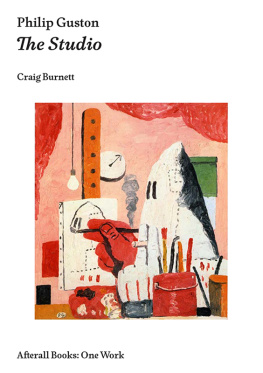

One Work is a unique series of books published by Afterall, based at Central Saint Martins in London. Each book presents a single work of art considered in detail by a single author. The focus of the series is on contemporary art and its aim is to provoke debate about significant moments in arts recent development.

Over the course of more than one hundred books, important works will be presented in a meticulous and generous manner by writers who believe passionately in the originality and significance of the works about which they have chosen to write. Each book contains a comprehensive and detailed formal description of the work, followed by a critical mapping of the aesthetic and cultural context in which it was made and has gone on to shape. The changing presentation and reception of the work throughout its existence is also discussed, and each writer stakes a claim on the influence their work has on the making and understanding of other works of art.

The books insist that a single contemporary work of art (in all of its different manifestations), through a unique and radical aesthetic articulation or invention, can affect our understanding of art in general. More than that, these books suggest that a single work of art can literally transform, however modestly, the way we look at and understand the world. In this sense the One Work series, while by no means exhaustive, will eventually become a veritable library of works of art that have made a difference.

First published in 2014

by Afterall Books

Afterall

Central Saint Martins

University of the Arts London

Granary Building

1 Granary Square

London N1C 4AA

www.afterall.org

Afterall, Central Saint Martins

University of the Arts London,

the artists and the authors.

eISBN: 9781846381409

eISBN: 9781846381416

eISBN: 9781846381423

Distribution by The MIT Press,

Cambridge, Massachusetts and London

www.mitpress.mit.edu

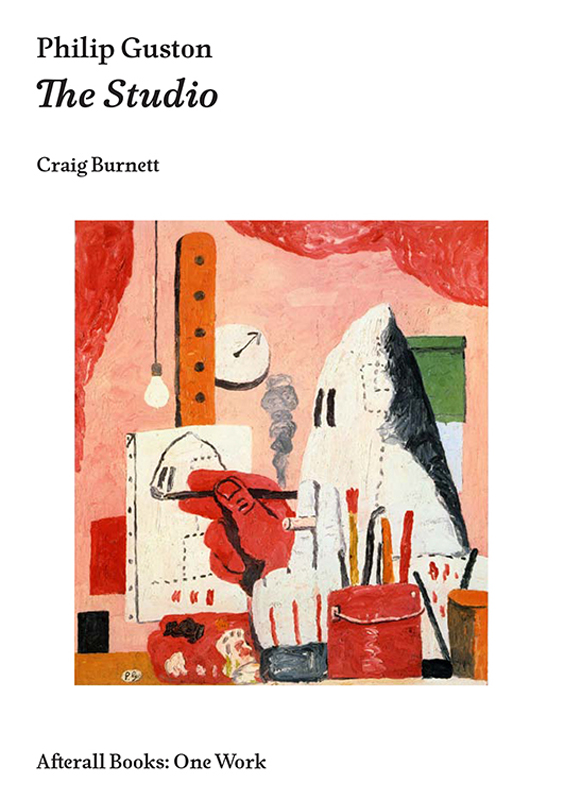

cover:

Philip Guston,

The Studio, 1969,

oil on canvas,

122 107cm

Private Collection

All works by Philip Guston and courtesy the Estate of Philip Guston and David McKee Gallery

Publication of this book has been aided by a grant from the Wyeth Foundation for American ArtPublication Fund of the College Art Association.

Enormous thanks to David McKee for his time and generosity, not only for arranging an extended viewing of The Studio but for his help with the McKee Gallery archive. Thanks to Clark Coolidge for his remarkable work on Philip Guston: Collected Writings, Lectures, and Conversations (2010); a boon for anyone interested in Guston, it had a huge impact on the direction of this book. Robert Slifkin, Annie Ochmanek, Stephanie Strasnick and Matt McAllester all supplied articles I couldn't get my hands on, for which I am grateful. An extra nod to Robert Slifkin for his superb Guston scholarship. For thoughts and conversation, I am indebted to David Anfam, Achim Borchardt-Hume and Tom Morton. For the dialogue between the hood's eyes and the puff of smoke, I stole many of the lines from poets and philisophers. Thanks, anonymously, to all of them. Finally, thanks to Eve and Lucas for the time and space, and to Elodie, for her enthusiastic love of pictures. The editors would like to thank The Estate of Philip Guston and David McKee for their generosity and support in providing material from the artist's archive during the production of this book.

Craig Burnett is a writer, curator and the author of Jeff Wall (2005).

1

Golla, all to a suddin I find out that Im all alone by myself alone would you rillze that?

George Herriman, Krazy Kat, 25 October 1925

Its 1969, it feels a bit like the end of the world outside, and a hooded thug slips into his studio for a quiet afternoon of painting. He sits down, squeezes out some black, white and orange paint onto a palette of primary red, puts on a dandyish white glove, lights a thick cigarette and gets t o work. He starts to paint what else? a self-portrait. He makes a few marks of red on the bottom of the canvas, a bit of blood, perhaps, from a bout of everyday brutishness, or maybe he just wants to test the red. He puts the red-tipped brush back into the bucket, takes out another brush and paints two black bars to indicate his eyes, some dotted lines for the stitching on the cloth of the hood, and then he starts to paint his hood. As he rounds the top of his head, he stops his brush in front of the two black bars of his eyes. The artist pauses. He seems stuck, lost in thought, mesmerised for a moment by the looming puff of smoke that obscures the space between the hood and his work.

What are we to make of this fat-fingered bozo? He paints, he smokes, he takes a break from murder and bigotry. Surely hes not worthy of our attention. Surely within an hour or two hell walk out of the studio and get whacked by a two-by-four or crash his jalopy. Maybe the implication here is that he wont taste a morsel of cartoonish justice, that even an everyday thug has the urge and the imagination to paint a self-portrait. But is the hooded figure even the subject of the painting? Although I began by describing the picture as a fragment of a story, as if it were a cell in a comic book, the painting is marked everywhere by a surfeit of suggestive, non-narrative details, formal red herrings, ghosts of abstraction. What is the black rectangle on the lower left? Does it depict a portal or an object, an abyss or a form? Why the fleshy red canopy, the overall pink glow, the red rectangle behind the canvas, the bulbous red hand, the clock with a single hand that points permanently to about two oclock? Its difficult to disentangle the artist himself from his subject, who seems to be in the process of creating the very picture he inhabits, of a homunculus with the power to conjure the monsters of his fancy. Something remarkable happens when this meathead is alone in his studio. Not only is he pretty good with the brush, but it looks like he can reflect, and reflect with wit, on the nature of his medium.

Philip Gustons The Studio (1969, Before the critics had even sharpened their hatchets, Guston knew that The Studio was a good painting, a turning point for him and, as it turned out, for the history of American painting.

Why has The Studio emerged over the past few decades as the icon of Gustons shift away from Greenbergian modernism and the New York School? Plenty of other candidates might serve the same purpose: Riding Around (1969, ), the long-running comic strip by George Herriman. The Studio is an ecstatic unleashing of everything Guston venerated, all bound together by a passage of supreme poetry: the totemic puff of smoke and the meatheads black-eyed apprehension of it at the centre of the picture. The work has grown in significance over the years because it might just be the best picture Guston painted in his life.

Few noticed at the time. Harold Rosenberg, informed by his friendship and conversations with the artist, responded with a long and thoughtful review in The New Yorker, And it is in The Studio, above all other works, where we see Guston sequestering himself and becoming that hero.

Lets imagine for a moment that Gustons career ended after his Recent Paintings and Drawings exhibition at the Jewish Museum in January 1966, where he showed austere black-and-white paintings (

Next page