Roussel, Raymond, 1877-1933.

[Impressions dAfrique. English]

Impressions of Africa / Raymond Roussel; translated [from the French] and with an introduction by Mark Polizzotti.

p. cm.

ISBN: 978-1-56478-624-1

1. Shipwreck victims--Fiction. 2. Captivity--Fiction. 3. Africa--Fiction. 4. Experimental

fiction. I. Polizzotti, Mark. II. Title.

PQ2635.O96168I513 2011

843.912--dc22

Partially funded by a grant from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Cet ouvrage, publi dans le cadre du programme daide la publication, bnficie du soutien du Ministre des Affaires Etrangres et du Service Culturel de lAmbassade de France reprsent aux Etats-Unis.

This work, published as part of a program of aid for publication, received support from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Cultural Services of the French Embassy in the United States.

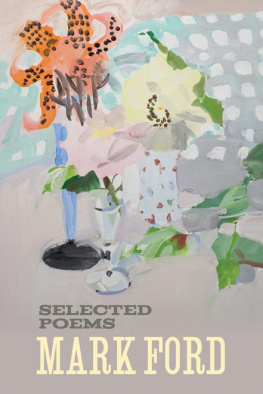

Cover illustration: Trevor Winkfield, Voyager IV . Acrylic on linen, 45 x 61 inches, 1997. Courtesy Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York.

I NTRODUCTION: A CHILDS GARDEN OF ECCENTRICITIES

K NOWNTO SOMEAS the Houdini of French literature, Raymond Roussel might also be its Peter Pan. The consummate verbal prestidigitator (Andr Breton dubbed him the greatest mesmerizer of modern times) carried in his bag of tricks enough material for at least ten times his actual output, and devised the sort of technological novelties that invite comparison both with his idol Jules Verne and with another of the twentieth centurys underrated oddballs, Nikola Tesla. In terms of compositional mechanics, his celebrated procd (method), though its full implications remain largely unexplored, has resurfaced in the writings of the Surrealists, the New Novelists, the Oulipo, and the New York School. But in many ways, Roussel was also the boy who never grew up. In page after page, the reader of his novels finds himself seated before a seemingly endless spectacle, staged, it would appear, for Roussels benefit alone. And as with many children of privilegewhich Roussel was in spadesany discomfort or damage suffered by the performer takes a distant backseat to the demanding tots enjoyment.

On the surface, in fact, Impressions of Africa , with its titular whiff of exoticism and H. Rider Haggard derring-do, would seem to appeal largely to an adolescents sense of thrill. On the Ides of March, somewhere at the dawn of the twentieth century, European passengers bound for Argentina survive a shipwreck and wash up on the shores of a fictive African nation. There they are taken captive by the vainglorious local potentate and held for several months, until sufficient ransom can arrive from Europe. So far we have the makings of a relatively standard adventure tale set in a far-off latitude where curious things can, and often do, occur. But these are no ordinary passengers, and this is no pastiche of King Solomons Mines (though Roussel, a fan of popular fiction, might well have read the book, judging by the similarity of the sovereign names Twala and Talou). In place of the intrepid Allan Quatermain, Roussel introduces a singularly gifted collection of castaways, ranging from circus freaks to inventors to scholars to theatrical prodigies, each, as luck would have it, a nonpareil in his or her specialty.

Indeed, very quickly the ostensible plot of African exile falls away, yielding to the authors real interest: a series of minutely described performances given by these castaways, as part of a gala they have devised to while away the time until deliverance. Theateror, more precisely, theatrical effect, the sense of marvel produced by magical and well-disguised artificeproves the most formidable protagonist of Impressions of Africa , and the novels various characters merely its instruments. The human plight of these characters, the suspense surrounding their release from captivity, ultimately takes on far less importance than the question of whether their performance will come off without a hitchand even that suspense is muted, for the true motor here is not whether the gimmick will work, but rather that it works and how it works. One can easily imagine Roussel, an avid theatergoer in real life, gaping with juvenile glee at the kaleidoscopic succession of wonders he has devised for his own amusement, each one following the last in a seamless and flawless procession, forming a world that is itself (as one critic put it) a theater in which people go to the theater.

The matter of performance is no idle conceit. Obsessed with fame, Roussel spent his adult life haunted by the alluring, and ultimately elusive, specter of public adulation. He described for his doctor, the renowned psychiatrist Pierre Janet, the sensation of glorious bliss he had experienced at the age of nineteen while writing his first long poem, La Doublure :

I was the equal of Dante and of Shakespeare, I was feeling what Victor Hugo had felt when he was seventy, what Napoleon had felt in 1811 and what Tannhuser had felt whilee musing on Venusberg: I experienced la gloire Whatever I wrote was surrounded by rays of light; I used to close the curtains, for I was afraid that the shining rays emanating from my pen might escape into the outside world through even the smallest chink; I wanted suddenly to throw back the screen and light up the world. To leave these papers lying about would have sent out rays of light as far as China, and the desperate crowd would have flung themselves upon my house.

Needless to say, when La Doublure was finally publishedat the authors expense, as its minute descriptions made it virtually unsalable, even for poetryit occasioned no such desperate flings, and Roussel sank into a depression from which he never fully recovered. Its lack of success shattered me, he wrote years later. I felt as though I had plummeted to earth from the prodigious summits of glory.

He nonetheless continued to write, in an unceasing bid for public acclaim. First he composed several more, equally hermetic, epics in verse; then, deciding that fiction was a surer road to bestseller-dom, the two novels that form his literary apex, Impressions of Africa (publishedagain at his expense, as ultimately were all his worksin 1910 ) and Locus Solus (1914). Finding the response to these books still rather lukewarm, Roussel set his sights on the theater as a more reliable audience magnet. He hired playwrights to adapt his two novels for the stage, financing the productions with dogged persistence, spendthrift profligacy, and the obliviousness to ridicule of a Florence Foster Jenkins; but his preference for long, abstruse monologues over discernible action put the shows beyond the pale of audience tolerance, and they fizzled after only a few performances. Undaunted, Roussel then turned to composing original stage works, starting with The Star on the Forehead (1925)its title a transparent metaphor for genius that figures in several of his writings, Impressions of Africa among themfollowed by The Dust of Suns in 1927. Like their predecessors, both were costly flops.