SPECIMEN DAYS AND COLLECT

Originally published by Reed Welsh & Co., Philadelphia, 1882

Copyright 2014 by Melville House

Introduction copyright 2014 by Leslie Jamison

First Melville House printing: November 2014

Melville House Publishing

145 Plymouth Street

Brooklyn, NY 11201

and

8 Blackstock Mews

Islington

London N4 2BT

mhpbooks.com facebook.com/mhpbooks @melvillehouse

Library of Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Whitman, Walt, 18191892.

[Prose works. Selections]

Specimen days; & Collect / Walt Whitman; introduction by Leslie Jamison.

pages cm (Neversink)

ISBN 978-1-61219-386-1 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-61219-387-8 (ebook)

1. Whitman, Walt, 18911892Diaries. 2. Poets, American19th centuryDiaries. 3. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Personal narratives. 4. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Hospitals. 5. United StatesCivilization19th century. I. Jamison, Leslie, 1983 II. Whitman, Walt, 18191892. Specimen days. III. Whitman, Walt, 18191892. Collect. IV. Title. V. Title: Specimen days and Collect.

PS3220.A1 2014

818 .308dc23

2014031520

Design by Christopher King

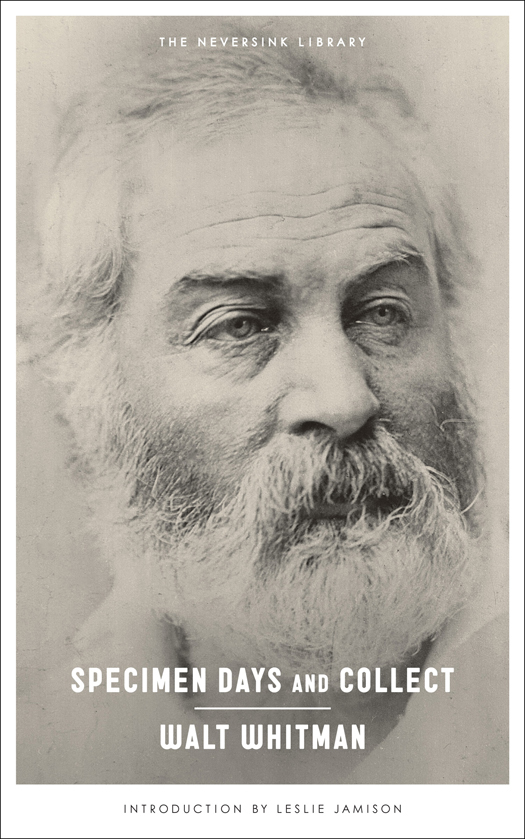

Cover photograph: Walt Whitman, 1863. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Divison.

v3.1

PRAISE FOR WALT WHITMAN AND SPECIMEN DAYS AND COLLECT

He is a great poet, our first, and it is unlikely indeed that his contribution to what it literally means to be an American poet will ever be equaled.

ROBERT CREELEY

I like or love Whitman unreservedly; he operates with great power and beauty over a very wide range.

JOHN BERRYMAN

Whitmans plan was to display an ideal democrat, not to devise a theory.

JORGE LUIS BORGES

I know no writer whose vision is as inclusive, as all-embracing as Whitmans.

HENRY MILLER

Whitman has gone further, in actual living expression, than any man, it seems to me.

D. H. LAWRENCE

Whitman was probably the first person in America who was not ashamed of the fact that he thought things that were as big as the Universe.

ALLEN GINSBERG

His discovery of himself is a discovery of America; he is able to give it to anyone who reaches his lines.

MURIEL RUKEYSER

I believe that long before Whitman came on the scene, ever since Milton in fact, poets writing in English unconsciously hungered for such a music as Whitman was to discover.

GALWAY KINNELL

SPECIMEN DAYS AND COLLECT

WALTER WALT WHITMAN (18191892) was born on May 31, 1819, in Huntington, New York. He left school at age eleven and went to work, first as an office boy, then as a printers devil and compositor at numerous newspapers in New York Cityhe even founded his own paper, the Long Islander, but sold it after ten months. His first publications were poems published anonymously in the New York Mirror. In the early 1850s, he began work on a collection of poetry, Leaves of Grass, which he paid to have printed at a local print shop. He would continue to revise the book over the course of his life, publishing by some counts nine different editions. The first edition was immediately polarizing: critics condemned it for its frankness about sexuality and its free-verse style. But others, like Ralph Waldo Emerson, saw in it a brilliant and uniquely American voicein a letter thanking him for the book, Emerson wrote, I greet you at the beginning of a great career. In 1862, in the midst of the Civil War, Whitman left New York and headed south to search for his brother George, who had been wounded at the Battle of Fredericksburg. Whitman found him safe and sound, but was so deeply affected by the sight of the devastation wrought by the war that he moved to Washington, D.C., and volunteered as a nurse in army hospitals. He also had a series of government jobs, including working for the Secretary of the Interiorwho subsequently fired Whitman on moral grounds, purportedly after reading Leaves of Grass. In the period after the war, Whitman published another collection of poetry, Drum-Taps, and the influential essay, Democratic Vistas. In 1873, he moved to his brothers house in Camden, New Jersey, to recover from a stroke. He would spend his final years there, surrounded by visitors and friends, among them Oscar Wilde and Thomas Eakins. When he died at the age of seventy-two, thousands followed his funeral procession.

LESLIE JAMISON is the author of a collection of essays, The Empathy Exams, and a novel, The Gin Closet. She is a regular columnist for The New York Times Book Review.

THE NEVERSINK LIBRARY

THE NEVERSINK LIBRARYI was by no means the only reader of books on board the Neversink. Several other sailors were diligent readers, though their studies did not lie in the way of belles-lettres. Their favourite authors were such as you may find at the book-stalls around Fulton Market; they were slightly physiological in their nature. My book experiences on board of the frigate proved an example of a fact which every booklover must have experienced before me, namely, that though public libraries have an imposing air, and doubtless contain invaluable volumes, yet, somehow, the books that prove most agreeable, grateful, and companionable, are those we pick up by chance here and there; those which seem put into our hands by Providence; those which pretend to little, but abound in much. HERMAN MELVILLE, WHITE JACKET

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

BY LESLIE JAMISON

What is Specimen Days? It doesnt sit easily in any genre. Its restless in its recounting. Structurally, its a collection of prose fragments written across two decades of Walt Whitmans life: his hospital visits during the Civil War; his recovery from a paralyzing stroke; his jaunts through the broad western states of America; his delight at trees and moths and glow-worms; his disappointment at the posturing of prairie women. In his own words, its a mlange of loafing, looking, hobbling, sitting, travelinga little thinking thrown in for salt, but very little wild and free and somewhat acridindeed more like cedar-plums than you might guess at first glance.

This is signature Whitman, deploying the rhetoric of explanation to make everything more mysterious: more like cedar-plums than you might guess at first glance. Hes right, of course: I hadnt imagined this book like cedar-plums at all. After helpfully describing what cedar-plums are (bunches of china-blue berries that grow along the cedars thick woolly tufts), Whitman explains that they resemble the book in their uselessness growing wild thin soil whence they cometheir content in being let alonetheir stolid and deaf repugnance to answering questions. Questions like the one that opened this introduction: What ARE you, anyway? We are invited to imagine the cedar-plums hanging there, blank-faced, refusing our inquiries.

Its a question perhaps best answered by way of list. The book is full of themlists of trees, lists of citiesand other accumulations, joyous and jarring: summer pleasures, urban streetscapes, bodies strewn across battlefields. The form of the list offered Whitman a kind of honesty in its refusal to imply any false totality or polish: it was just a rough accounting, a ledger of the war dead, a catalog of the world.