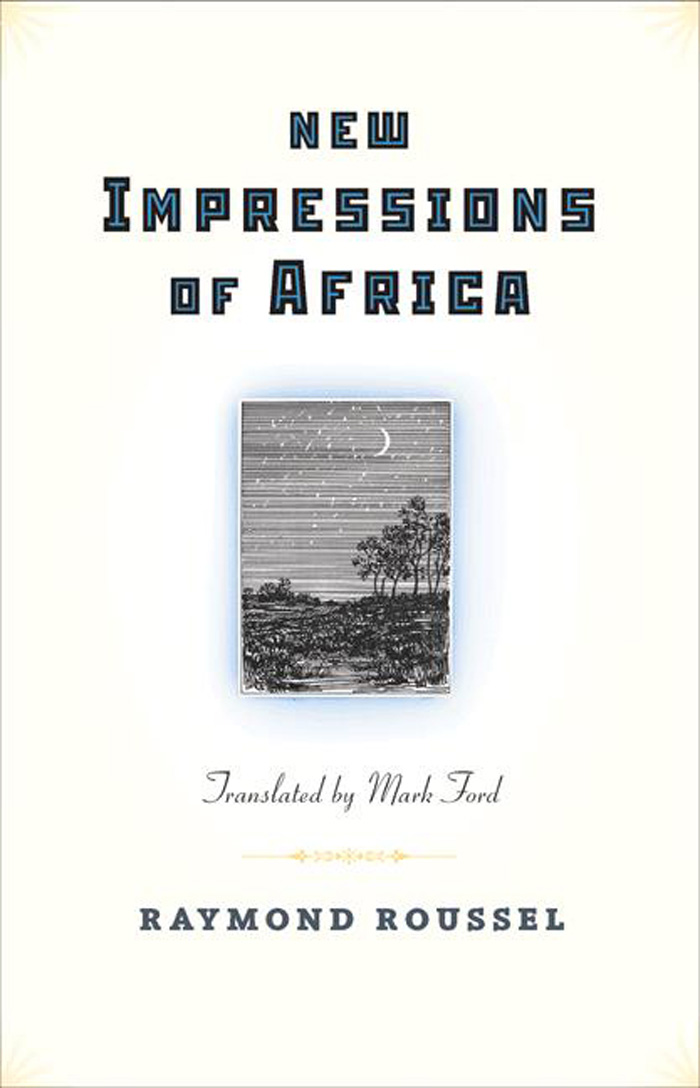

New Impressions of Africa

Nouvelles Impressions dAfrique

FACING PAGES

NICHOLAS JENKINS

Series Editor

After Every War: Twentieth-Century Women Poets

translations from the German by Eavan Boland

Horace, the Odes: New Translations by Contemporary Poets

edited by J. D. McClatchy

Hothouses: Poems, 1889

by Maurice Maeterlinck

translated by Richard Howard

Landscape with Rowers: Poetry from the Netherlands

translated and introduced by J. M. Coetzee

The Night

by Jaime Saenz

translated and introduced by Forrest Gander and Kent Johnson

Love Lessons: Selected Poems of Alda Merini

translated by Susan Stewart

Angina Days: Selected Poems

by Gnter Eich

edited and introduced by Michael Hofmann

Oranges and Snow: Selected Poems of Milan Djordjevi

translated from the Serbian by Charles Simic

New Impressions of Africa

by Raymond Roussel

translated with an introduction and notes by Mark Ford

New Impressions of Africa

Nouvelles Impressions dAfrique

R AYMOND R OUSSEL

I LLUSTRATIONS BY H ENRI -A. Z O

Translated with an introduction and notes by Mark Ford

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Princeton & Oxford

Copyright 2011 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Roussel, Raymond, 18771933.

[Nouvelles impressions dAfrique. English & French]

New impressions of Africa = Nouvelles impressions dAfrique / Raymond Roussel ; translated with an introduction and notes by Mark Ford.

p. cm. (Facing pages)

French with English translation on facing pages.

ISBN 978-0-691-14459-7 (cloth : alk. paper)

I. Ford, Mark, 1962 June 24- II. Title. III. Title: Nouvelles impressions dAfrique.

PQ2635.O96168N613 2011

841.912dc22 2010035414

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Adobe Garamond

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

this translation

is dedicated to

John Ashbery

Contents

Introduction

Nouvelles Impressions dAfrique is the last work that the French poet, playwright, and novelist Raymond Roussel published during his lifetime. He began drafting it in 1915, but the poem was not to appear until the autumn of 1932, less than a year before its author was found dead in his room at the Grande Albergo e delle Palme in Palermo, Sicily at the age of 56. On ne saurait croire, he observed in his posthumously published essay, Comment jai crit certains de mes livres, quel temps immense exige la composition de vers de ce genre (It is hard to believe the immense amount of time composition of this kind of verse requires).

The poem consists of four cantos of 228, 642, 172, and 232 lines respectively. Each is prefaced by a heading referring to a location in Egypt, and each begins with a few lines evoking the location in question. Rasant le Nil, opens brackets, removing us yet further from the cantos opening lines of description or meditation.

Each canto is, thus, grammatically, one enormously long sentence, and to complete its opening syntactic unit you have to turn forward to the lines that succeed the cantos final closing bracket.

I hope that what Roussel meant when he talked of the immense amount of time demanded by composition de vers de ce genre is becoming clear. The main text of each canto contains only one full stop, that which comes after the final line, although he does make frequent use of exclamation marks, question marks, and ellipses [...] as means of avoiding infringing this taboo. The only full stop allowed in a footnote, similarly, comes at its conclusion. Each single, vast, labyrinthine sentence hangs, therefore, from a single main verb: in it occurs in line 1: je voiswhich is the only time Roussel appears in person in the poem.

Like the vast majority of Roussels poetry, Nouvelless Impressions dAfrique is written in rhyming alexandrine couplets (i.e., twelve-syllable lines) that alternate masculine and feminine rhymes (in French, feminine rhymes end in a mute e, masculine rhymes dont). From the outset of his career as a poet Roussel established the habit of kick-starting composition by setting out a list of rhyming words down the right-hand side of the page, and in the very early Mon Ame, published in 1897, a poem that unequivocally and unabashedly celebrates his own extraordinary literary talents, he figures his creative soul as a factory in which a vast army of workers extract from the fiery gulf of his inner being numerous rimes jaillissant en masse (rhymes flying like masses of sparks). By the time Roussel temporarily abandoned verse in his late 20s, to write the novels Impressions dAfrique and Locus Solus, he had already composed around 25,000 lines in rhyming alexandrines; it seems to me likely that the ingenious constraints he imposed on himself when he took up verse again in 1915 were a practical way of disciplining his almost unstoppable poetic fluency.

, for instance, Roussel offers a list of the different ways in which various people make lots of money in America; one person does so by selling heaps of pictures to a snobbish stockbroker:

Soit que par stocks on vende lagioteur snob

(((Le rle du snobisme ((((au vrai qutait Jacob?1

1. Mme est-on sr que Dieu, quand il fit le snobisme

(Si lanimal ne sait pas plus percer un isthme...

Whether one sells in heaps to the speculator whos a snob

(((The role played by snobbery ((((in essence, what was Jacob?1

1. Can one even be sure that God, when he made snobbery

(If animals no more know how to build a canal across an isthmus...

(lines 5556 and footnote 1, lines 12)

This is the poems most accelerated series of transitions: the triple bracket introduces the assertion that snobbery will always play a major role in life, and the quadruple bracket the novel idea that Jacoband Esau too!were snobs in their wrangling over a birthright; the footnote launches the notion that God possibly made animals snobs as well as men, and the first bracket within the footnote ponders the relationship between men and animals, who may not be able to build a canal across an isthmus or do various other things that men can dobut arent we a bit like pigs, this particular parenthesis closes, or life-saving dogs?

Ne retrouvons-nous pas nos instincts chez les porcs?

Chez les chiens sauveteurs qui foncent la nage?),

Do we not rediscover our own instincts in pigs?

In life-saving dogs when they plunge into the water?),

(Footnote 1, lines 89)

Like much of Roussels best writing, Nouvelles Impressions dAfrique is extremely funny, and beautiful, but its humor and beauty are not easy to define. Reading through the vast collection of his manuscripts housed in the Fonds Roussel in the Manuscript Department of the old Bibliothque Nationale on Rue Richelieu in order to write my critical biography of him (Raymond Roussel and the Republic of Dreams [2001]), I occasionally wondered if he suffered from Aspergers syndrome, or a mild form of autism. He had, to quote Robert Desnos,