To Jake,

for igniting this journey and for being there

every step of the way... my inspiration.

You gain strength, and courage, and confidence by

every experience in which you really stop to look

fear in the face... you must do the thing

you think you cannot do.

Eleanor Roosevelt Not everything that is face can be changed, but

nothing can be changed until it is faced.

James Baldwin

CONTENTS

Guide

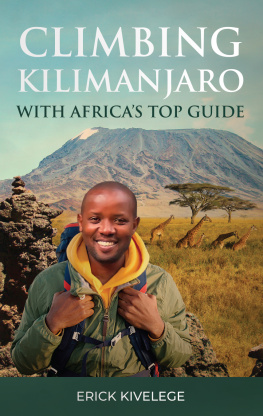

F orce away the pain. Fight your fight. One more step. You are an Ironman, Bonner Paddock. You are an Ironman.

I silently repeat it, over and over. You are an Ironman. The words are a promise. They are an aspiration. If I finishno, when I finishbefore the midnight cutoff, the announcer will shout them out to the world, and they will become fact. But right now I am running alone in the inky blackness of a Hawaiian island night, my headlamp is casting a small wobbling circle of light on the broken pavement ahead, and I am struggling.

Passing into my 17th mile, I know I am in trouble. Every inch of my body screams in pain. I want nothing more than to stop, collapse into a heap, and end this torture. With each troubled stride, my knees bend in, and my ankles flail out: my legs are breaking down. At some point, fast approaching, determination will no longer be enough to keep me moving.

One second I want to quit. The next, I force away the thought. I have battled these doubts throughout the 2.4-mile swim in swelling seas, on the 112-mile bike ride in devil-searing heat, and now during the final miles of the marathon run of the 2012 Ironman World Championship.

You are an Ironman. Force away the pain. Fight your fight. One more step. You are an Ironman. My mantra keeps me moving for another hundred yards, but then I slow down, almost to a walk.

Im running through the Natural Energy Laboratory property, just off the Queen Kaahumanu Highway. The government installation is the farthest point away from Kailua-Kona, home base. The Energy Lab is dark, cant-see-your-hand-in-front-of-your-face dark. Day or night, it is creepy too, with windowless sheet-metal buildings and huge black pipelines that snake through the grounds before plunging into the ocean. Worst of all, the lab boasts the reputation, confirmed many times by my coach, Ironman legend Greg Welch, for being the place that makes or breaks competitors. Top pros have entered this stretch, roughly Miles 1619 of the marathon, in the lead only to fall far behind by the time they emerge. Many other racers have left on stretchers. The heat, the absence of a breeze, the sheer haunting barrennessthey are often too much to bear.

Time is running out for me. Since 7 A.M., when the sun rose over the summit of Mount Hualalai, one of the Big Islands five active volcanoes, Ive been pushing my body. More than fourteen hours with no rest and no reprieve. My legs feel mashed to a pulp. My feet burn with every step, each foot a wet, bloody, swelling mess laced into its shoe. At any moment the race officialsGrim Reapers on scootersare going to sweep me up.

Too slow, Bonner. You wont make the cutoff, they will say.

No can do, theyll continue. Were sorry. You had a good race. At least you gave it your best.

No.

My best I have yet to give. I dig inside of myself, deeper than before. I quicken my pace slightly, but enough to bring the pain roaring back. So be it. Use the pain. Ignore the rest. Step after step. I head down toward the ocean, then bank right, going north now.

I worry that I am sweating too much. I worry that I am moving too fast. Then I worry that I am moving too slowly. I want to know the time, but I worry that if I look at my watch I will lose my balance and fall. I need to use my sight to keep my balance. I worry about the rising twinge in my ankles. I worry that my body is not keeping in any of the liquid I am drinking. I worry that I am hitting the wall, that Ill faint. I worry that I will stumble off the road into the lava fields and that nobody will know where Ive gone. There I will lie until they find me, and all that will remain will be the desiccated skeleton of Bonner Paddock. I am not thinking straight, havent for hours. I feel so isolated and so alone.

Keep the strides long, mate. Keep your pace even, Welchy says. Move your arms. I turn to find my coach jogging along beside me. Hes wearing flip-flops. How I would love to be wearing flip-flops. His wife, Sian, also an Ironman champion, is chugging down the road on a scooter. Why are they here? I left them back on the Queen K Highway before I turned into the Energy Lab. They said they would meet me at the finish.

Ill never quit, Welchy, I say.

I know, he says. Just remember to drink chicken broth at the next aid station and keep running your own race.

Okay, okay.

Theres a ton of big blue cowboy hats waiting at the finish for you.

My body trembles. My toes explode with each step. I stare down at the road. When I look back to my coach, he is gone, as is Sian. Poof. As if they were never there.

I am not alone, I remind myself. I never have been. My coach is with me. All my friends and family down at the finish line in big blue foam cowboy hats are with me. My brother Mike, who saw me through every bump and roadblock of this journey, is with me. Juliana is with me. Steve Robert and his family are with me. And Jake, dear Jakey, is with me, as he was at the very beginning when I knew absolutely nothing of myselfand accepted even less.

Ahead I see a bright white light. Its not heaven, but close enough. Its the Energy Lab turnaround. Once I reach it, I will be heading back toward the finish, toward home.

Force away the pain. Fight your fight. One more step. You are an Ironman, Bonner Paddock. You are an Ironman.

T he alarm buzzed. I hit the snooze button. The alarm buzzed again. I hit snooze again and turned over. On the third buzz, I sat up in bed. Time to get the day on. It was March 2005. Life was good. Life was normal. At twenty-nine, I finally had some money in my pocket and a dream sales job on a professional sports team. Yes, I had racked up some serious credit-card and student-loan debt, but who hadnt at my age, I figured.

I lived in Newport Coast, California, a mile from the ocean, in a one-bedroom, 850-square-foot bachelor pad. I had the big-screen TV, racks of CDs, a closet full of suits, an oversized couch, and a refrigerator with all the essentials: beer, mustard, ketchup, Tabasco sauce, and flour tortillas for bean and cheese burritos. The beige walls, which matched the beige carpet, were bare but for a black-and-white photograph of some hanging garlic taken by my grandfather. The apartment complex boasted a pool and a small gym. The silver Lexus parked in the garage was perfect for rolling to work and for getting to parties on the weekends (or even during the weekhey, I was young). Normal. Happy.

The fact of my having cerebral palsy? Only my family and close friends knew about thatand then not all of them did. Because the nature of my cerebral palsy allowed me to keep it a secret, that was exactly what I did. Sitting across from me at a meeting or over dinner, people saw a big guy, six foot four, with the wingspan of a basketball player and hair that was maybe thinning a little too early. I smiled a lot and talked fast and furiously. Nothing wrong with me. All was well.

That morning when I finally rolled out of bed and put my feet on the floor was like every morning. There was no avoiding the stiffness and pain. Try holding your hand tight in a fist for as long as possible. Really concentrate and push yourself. Feel that burn start in your fingers and then move down your wrist into your forearm. That is how my feet, calves, hamstrings, quads, glutes, and lower back feelall the time. There is no loosening, no release. Every morning it feels as though I hit the gym the night before for the first time ever, really pushing it to the limit, and now my body is mad at me, really mad.

Next page