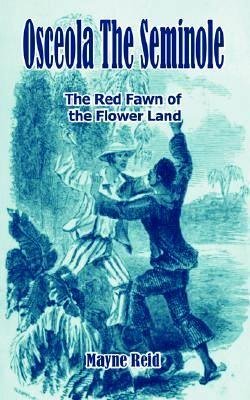

Seminole Chief Osceola

The Seminoles had lived peacefully with Spanish settlers and runaway slaves until Florida became part of the United States. When the U.S. government decided the Seminoles should be moved to distant reservations, Seminole Chief Osceola led his people into war.

Based on the words of Osceola and on other historical accounts, the author tells the real story of this fearless leader, in one of the longest struggles of the Indian War.

About the Author

William R. Sanford is the author of numerous books for young people. He brings many years of teaching experience to the books he has created.

This book tells the true story of the Seminole warrior Osceola. Many mistakenly think he was the chief of all his tribe. But his true fame rests on his leadership in war. He led the Seminoles fight against the U.S. Army. At the time the press rushed to print stories about Osceola. Some were made up, but others were true. The events described in this book all really happened.

Osceola has not been forgotten. Three counties, two mountains, and a national forest carry his name. There are also twenty towns named Osceola.

Image Credit: Clipart.com

Osceola stabbed the treaty that paid the Seminoles. They had taken money in return for agreeing to move out of Florida.

Wiley Thompson glared at Osceola. Would the young Seminole block his well-laid plan? Thompson was the Indian agent at Fort King, Florida. His job was to carry out U.S. government policy on the Seminole reservation.

Now, in 1835, Thompson had summoned the Seminole chiefs for a talk. The government wanted the Seminoles land. He told the chiefs they would have to move. They each made their mark on a treaty. Thompson gave the bands of these chiefs a nine-month delay. During this time the bands could harvest crops and round up cattle. They would arrive in the West in time for spring planting. Five chiefs did not sign. In anger Thompson slashed their names from the list of chiefs.

Thompson then looked to Osceola. The Seminole stood with his arms folded across his chest. At thirty-one he stood five feet, eight inches. His walk was firm. And he had a handsome open look. His eyes were calm; his nose, straight; and his lips, thin.

Osceola moved forward. He returned Thompsons glare. Drawing his knife, he stabbed it into the wood of the table. This is the only way I sign, he cried Then Osceola yanked out his blade. And with the stride of a hunter, he left the fort.

Thompson feared the Seminoles might fight rather than move. So he issued an order. The fort would sell the tribe no more lead, powder, or guns. Osceola was angry. A few days later he stamped into Thompsons office.

Osceola warned, I will make the white man red with blood.... Then [I will] blacken him in the sun and rain. The wolf shall smell of his bones. The buzzard [shall] live upon his flesh.

In June, Osceola came again to Fort King. With him was his wife Morning Dew, who was part black. A slave trader claimed that she was a runaway slave. He would take her away with him. Thompson listened to the argument. He said there was no proof the woman was not a runaway. The trader clapped her in irons and took her away. Osceola strongly objected. Thompson ordered soldiers to put Osceola in the fort prison. They put shackles on his ankles. He sat silently for two days.

In speaking to Osceola, Thompson revealed what lay behind his actions. Would the Seminole agree to persuade all the chiefs to move? If so he could go free. At the end of six days Osceola agreed to do what Thompson wanted. Once he was free he left the fort. When he reached the edge of the woods Osceola turned. He roared, Yo he e hee! It was the Seminole war cry.

The Seminole chiefs met. All agreed to resist Thompsons plan. They would kill any chief who agreed to move. Charley Emathla was among the chiefs who refused to move. But in November he changed his mind. Charley had agreed to take his band to Fort Brooke. There, ships were waiting to take his band west.

At Fort King, Emathla sold his bands cattle. He received a small bag of coins in payment. On his way home Emathla was surrounded by twelve warriors led by Osceola. Osceola asked Emathla to join in the fight against the whites. When Emathla refused, Osceola fired his gun twice. Emathla fell to the ground dead. Osceola then picked up the bag of coins. This is made of red mens blood, he cried. He threw the coins into the woods. With this murder, Osceola began the Second Seminole War.

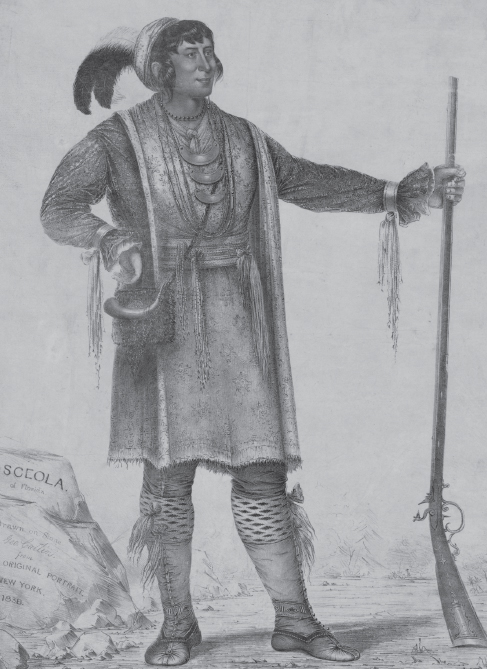

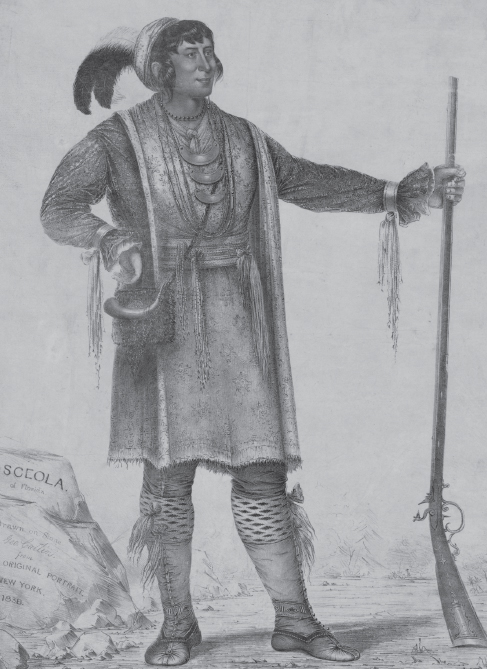

Image Credit: Library of Congress

This drawing of Osceola accurately portrays the Seminole leaders dress and weapons.

Osceola was born in 1804 in what is now Macon County, Alabama. His name at birth was Billy Powell. His mother, Polly was half Creek, half Scot. She told Billy his father was a Creek warrior. He had died before Billy was born. Around that time Polly married William Powell. Powell, a lean quiet Englishman, was a trader. He traded with the Creeks for skins and blankets.

The family lived in a square one-room cabin. Pine logs formed the walls, and pine bark thatched the steep roof. A few blankets separated, the living quarters from Powells trade goods that filled one end of the cabin. Billy slept on a wooden bench covered with deer skins. Near the house grew a few rows of vegetables, corn, and melons.

In 1812, the United States and England went to war. The Creeks divided their loyalty between the two countries. One branch, the White Sticks, sided with the Americans.

The other, the Red Sticks, aided the British. The Red Sticks killed three hundred settlers and soldiers at Fort Mims, Alabama. Two years later Andrew Jackson defeated the Red Sticks at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. Troops from Georgia surged through the region. They killed every Creek they found. The soldiers did not care which branch of the tribe a Creek belonged to.

One day Powell went into the woods with his musket. He never returned. Polly knew the white soldiers must be coming close. She crammed what little she owned into two packs. Then she and Billy joined a band of Red Sticks fleeing south. They all hoped to find safety in Florida, which was Spanish land then.

But mother and son could not keep up with the band. So they finished the five-hundred-mile trip alone. At last they reached the sand hills of west Florida. There they lived in the village of Peter McQueen, Pollys uncle. The village lay on high ground above a river. The river was full of fish, and the soil was fertile.

In 1815, McQueens band moved near the Spanish town of St. Marks. There they mingled with the Seminoles. The Seminoles were a branch of the Creeks. They once lived in the southeastern United States. By the mid-1700s, the Creek homeland was overcrowded. So the Seminoles moved south to Florida.

Troubles on the Florida border led to the First Seminole War. In 1818, Jackson invaded Florida. He attacked McQueens village, killing thirty-seven braves. Jackson captured Billy and his mother. When he released them, they went to a village on Tampa Bay. There Billy grew to manhood.

Each June the band staged a Green Corn Dance. At that time young men such as Billy went through a ceremony to become a warrior. Billy dressed in a blue breech clout. He wore leggings and soft moccasins. Quills and plumes trimmed his headband. Red paint covered his chest. Billys earlobes were slit and then lengthened with weights. A medicine man scratched him with a needle. Soon Billy bled from the arms, legs, chest, and back. Bleeding, the Seminoles believed, purified the blood. The medicine man handed Billy a bowl of Asi, the Black Drink. It contained ground snakeroot, willow bark, red bay, wild grapes, and roots.