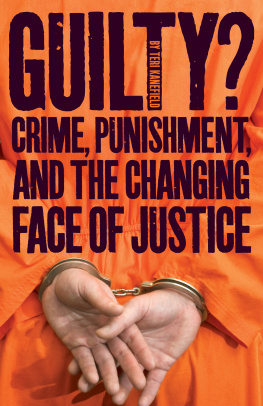

Copyright 2014 by Teri Kanefield

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhco.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Kanefield, Teri, 1960 author.

Guilty : crime, punishment, and the changing face of criminal justice / by Teri Kanefield. p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-544-14896-3

1. Criminal justice, Administration ofUnited StatesJuvenile literature. 2. Guilt (Law)United StatesJuvenile literature. 3. Judicial processUnited StatesJuvenile literature. I. Title.

KF9223.K29 2014

364.973dc23

2013042010

eISBN 978-0-544-46556-5

v1.1114

For Andy

Introduction

That ought to be a crime!

People should not be allowed to get away with that behavior!

We need to be tougher on crime!

Police officers need to get criminals off the streets so law-abiding citizens can live in peace.

Statements like these, often heard on television and elsewhere, represent the crime control model of criminal law. Under this model, law and order is the ideal. Preventing crime is the most important function of criminal law, becauseaccording to this theorywithout law and order, you cannot have a free society and people cannot feel secure.

The crime control model values well-trained and efficient police squads that know how to investigate a crime scene, preserve evidence, question suspects, and efficiently figure out who most likely committed the crime so the culprit can be brought to justice. The crime control model is based on the assumption that crimes are committed by bad people who belong in jail, which in turn is based on the belief that criminal laws represent absolute standards of right and wrong.

The crime control model is one with which almost everyone is familiar, and with which many people feel comfortable. But this doesnt mean the crime control model doesnt have problems and flaws. For example, ideas about what should be criminalized spring from ever-changing cultural beliefs, and thus change over time and across cultures. If reasonable people can disagree about what behavior to criminalize, how can we be sure that the behavior we are criminalizing is morally wrong? Or that the behavior we are not criminalizing is morally acceptable?

If defining crimes presents moral dilemmas, deciding when and how a government should inflict punishment presents even more difficult moral questions.

There is another model of criminal law: the due process model, which values individual liberty above crime control. Many of those who favor the due process model agree that there are dangerous people out there who need to be stopped, but they also believe that being too tough on crime causes more problems than it solves. The due process model embraces the idea that it is better for a guilty person to walk free than an innocent person to be put in jailso the due process model makes it more difficult for citizens to be arrested, tried, and punished.

Critics of the due process model point out that people should be accountable for their behavior and a system that might allow a guilty person to walk free is deeply flawed.

The two models offer different ways to think about the issues.

For some, the ideal system embraces the values from both models and seeks a balance between the two.

With criminal law, as with ethics in general, there are often no clear-cut answers.

Because legal reasoning is all about comparing cases, the material in this book will be introduced the same way as it is in law school: through real-world cases showing issues in their full complexity.

DECIDING WHAT BEHAVIOR TO CRIMINALIZE

People often use the word crime to mean something badbut the legal definition of a crime is an act that the law makes punishable. Nothing more, nothing less. If there is no law against a particular behavior, it isnt a crime, no matter how bad it is.

A crime is different from other forms of wrongdoing in that a crime is seen as harmful to society as a whole, which is why the police get involved and the government prosecutes and punishes people.

Human beings err, but not all bad behavior can be criminalized. In fact, criminalizing every bad or dangerous action would be impossible. Take smoking, for example. The National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion calls smoking the single most preventable cause of disease and death in the United States. Smoking is harmful not just to the smoker, but to others through secondhand smoke. Smoking causes harm to all society by creating large medical costs, but smoking has a history in our culture of being socially acceptable, and not too long ago was even considered glamorous.

A society has to decide which wrong and harmful behaviors to criminalize. But how do we decide what to criminalize? How do we know if we are right?

CRIMES OF OPPORTUNITY: THEFTOR GOOD LUCK?

James Rogers walked into a bank with a check for $97.82 made out to his brother. He gave the check to the teller and, following his brothers instructions, asked her to deposit $80 into his brothers bank account and give him the remaining $17.82 in cash.

The teller wasnt sure how to do this, so she asked another employee how to handle the transaction. Her colleague told her she could deposit a check in part, and cash the remainder. The math was easy: just subtract the $80 from the original $97.82 and give James the change.

James signed the check, writing the date, December 6, 1959, as 12 06 59. The telleraccording to the story that emerged laterconfused the date of the check with the dollar amount and thought the amount was for $1,206.59. She deducted $80, which she deposited into the account, and put the change on the counter: $1,126.59.

One thousand dollars in 1959 was the equivalent of almost nine thousand today. James picked up the money and walked out of that bank with a windfall.

At the end of the day, the tellers cash box was short $1,108.77the amount the teller gave James minus the $17.82 she was supposed to have given him.

James was arrested, charged with bank robbery, and brought to trial.

According to traditional definitions, robbery requires taking something of value by force or threat, or by putting the victim in fear. The federal bank robbery statute under which James was convicted, however, defines bank robbery as carrying away money belonging to a bank with the intent to keep the money. If the amount is over one thousand dollars, the crime is a felony, which is a serious crime. Carrying away less than one thousand dollars is also a crime, but a misdemeanor, which means a lighter punishment.

At his trial, James denied that the teller had given him the extra money. He said she gave him the $17.82 he was owed. The prosecutor submitted as evidence against James the tape from the tellers adding machine showing that she had accepted the check as having been written for $1,206.59.

The jurys task was to decide who was telling the truth.

Next page

![Laura L. Finley - Crime and Punishment in America: An Encyclopedia of Trends and Controversies in the Justice System [2 Volumes]](/uploads/posts/book/305562/thumbs/laura-l-finley-crime-and-punishment-in-america.jpg)