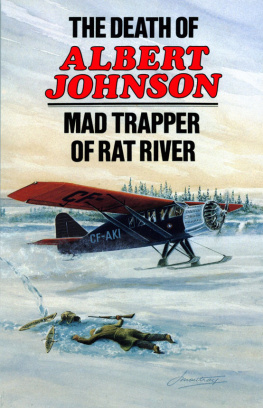

Not far out on a frozen lake, a tall, slim man was chopping at a water hole with an axe, his breath rising in a steady stream and hovering in a cloud above his head. He wore a toque, a heavy, red-and-black plaid wool shirt, wool pants held up by red suspenders, moccasins and long sheepskin mitts. He was remembering to be careful, to do things slowly, to hang on tight so that if the handle hit the rim of the hole, the axe wouldnt jerk out of his hands and disappear into the lake. He checked the axe head regularly, making sure it was tight.

We only got two of these, Joe, Bill had said. And the spare one aint so good.

A Newfoundland dog was standing on the ice nearby, watching, tail wagging slowly.

Behind Joe and his dog was a sod-roofed log cabin, huddled in snow. Smoke billowed from the chimney and disappeared immediately into the grey, low-hanging clouds. The cabins gabled end, with a tiny window, faced the lake. Joes snowshoes were propped against the wall, and a 45-gallon fuel drum with the letters DAL painted on its side sat near the trail leading from the cabin to the lake. Light, barely perceptible snowflakes were falling onto the lake and the spruce-furred hills around it.

Joe rested a moment, gazing toward the far end of the lake. Soon, Bill would appear there and cross the lake to the cabin. They would compare each others catches from their respective parts of the trapline.

A couple of hours earlier, Joe had come in with three marten, a fox and a wolverine, the last rare according to the boys in Fort Simpson, worth little at the trading post but saleable locally at a good price as parka trim. All of Joes catch was now hanging from the cabin ceiling, defrosting. Tomorrow, he would start pelting and scraping.

The wolverine had had his paw well in the set and hadnt been there for long, still jerking hard on the chain and gnawing on it and his own leg, scarcely even looking up when Joe appeared. A shot to the head finished it. It was the first time hed ever had to shoot something on the line, shells being expensive, as Bill had also pointed out. But there was no way he was going to try clubbing the thing to death.

Wolverine hardly ever got caught in traps. Maybe Bill would have some stories and theories about this one. It didnt look emaciated from sickness, old age or hunger; its coat glistened like silk. It might have been young and inexperienced. Some of the locals believed that the animal was subject to snow blindness. If so, it could have walked into the trap.

Joes recent catch, if he prepared the pelts right, was worth maybe $60 down at the post, more money than hed ever earned before over only three days. Five days altogether, if you counted preparation. And so far, after only three months, they had, Bill figured, over $1,000 worth of marten and lynx in the cache. Bill was obviously happy. It had taken a month, down along the Liard River, to bring in $100. Theyd put in almost three months there when the pilot suggested flying to the lake. Its the best marten country I know of, hed said. And theres no one working it. Im letting my camp below the hotsprings sit idle until next year. You guys will have the place to yourselves.

And the flight in cost only $100.

When Bill came across the lake with his catch, theyd cook some moose steak. Then, an evening at cards, trying to beat the unbeatable Bill Eppler. The prize, Bill had announced on their first night in camp, was the one bed in the cabin, a pole-box on four blocks of firewood. The box held spruce boughsthe beds mattress. There was a question of whether it was any more comfortable than the pile of boughs kept beneath it for spreading a second bed on the floor, but Bill always said that it was a spiritual thing, that the person in the official bed slept on a higher plane.

So far, Joe had spent only a couple of nights on the real bed.

Bills one of the best, Joes older brother, Jack, had said. Youll learn right from him, and hes an easy man to be with.

The young man resumed chopping, then took his bucket, got down on his knees and pushed it into the hole. To reach water, he had to get his head and shoulders below the surface of the ice. He rose again, slowly, the bucket full, then stood for a moment, his gaze at the far end of the lake. A breeze had come up; it was blowing into his face from the south.

Gettin warmer, he said. Gonna blizzard, maybe, Ghengis. The dogs tail wagged faster. Bill should be close.

He picked up the axe with his free hand and walked the path to the cabin. When he reached the door he leaned the axe against the frame and reached for the door handle, only to be startled by a loud growl and then a rush of frantic barking from Ghengis. As he turned to look, a gunshot exploded. Ghengis tumbled onto the snow a few yards away and lay still.

A man stood at the edge of the clearing, his rifle not shouldered but held at hip level, still pointed at Ghengis. He was tall, heavy and bearded, and clad in fura hat with ear flaps, a thick coat and leggings. His pack was topped with a bulky sleeping bag.

Joe scarcely looked at him. He was staring in disbelief at Ghengis. What the bloody hell did you do that for?

Your dog was coming at me.

I guess so! I woulda called him off. Whered you come from?

How long you been here?

Three months.

That your line back there?

The young man looked up and saw that his questioners rifle was now pointing at him, and this made him angry. Who are you?

You with a partner?

I said who are you?

Maybe you already know who I am. Maybe you been watching me.

Just tell me your name, if you can remember it.

A shot rang out, and Joe spun around and slumped silently into the snow, the water bucket tipping as he went down.

The man with the rifle walked toward the cabin and stood for a while examining the patch of blood spreading brightly through the young mans shirt. Then he said, Francis John Wade, Private, K-2558.

He turned, walked to the shore of the lake and stood scanning the shoreline carefully. Then he focused his attention on the fuel drum. The pilot, he said. He returned to the cabin and removed his pack and showshoes, propping them against the wall. Pushing the cabin door open, he disappeared inside, emerging a few minutes later with a tin of tobacco. He opened the tin, looked inside, pulled a lighter out of it, examined the lighter, turning it around in his hands, then dropped it back in the tin and stuck the tin under his arm. Seizing his snowshoes, he carried them into the trees behind the cabin.

The cache was uncovered, a ladder against its front and a white tarp hanging down from its back. A long wooden toboggan leaned against one of the support trees, a small tarp tucked into its tie-down rope. Wade mounted the ladder and examined the contents of the cache. He picked up a rifle and examined it.

Thirty-thirty, he said. He reached back into the cache and produced a box of shells. He descended the ladder, propped the rifle against a tree, placed the shells on the snow and ascended again.

Can of paint. Roll of canvas. Mustve been planning some improvements. Some food. I can use that. A bit of moose meat.

He reached farther into the cache. Good take of marten, he mumbled. Two bundles of pelts hit the ground.

Lynx. Another bundle hit the ground.

Wade came back down the ladder carrying a couple of small food bags, which he loaded into his pack. He laid the toboggan on the snow and piled the bundled pelts onto it, putting the rifle and box of shells in the middle of the pile. It was snowing more heavily, so he tied the whole load down with the small tarp and a rope that was already attached to the toboggans side.

Back at the cabin, he rolled his victim over and seized him under the shoulders, dragging him and the water bucket, now frozen in the dead mans hand, inside. He took the dog by a hind leg and dragged him into the cabin too. Then, moving faster, he walked toward the lake. He kicked the fuel barrel loose from the frozen ground, pushed it over and rolled it to the cabin door, where he stood it up. He used the axe to tap the spigot open and then threw the axe into the cabin and pushed the barrel after it.