Praise for Douglas A. Blackmon's

S L A V E R Y

BY ANOTHER NAME

"Vividly and engagingly recalls the horror and sheer magnitude ofneo- slavery and reminds us how long after emancipation such practices per sisted. Provides insights on how we might regard the legacy of slavery, reparations, and perhaps even our justice and correctional system, with echoes for our own time."

The Boston Globe

"A terrific journalist and gifted writer, Blackmon is fearless in going wher ever the research leads him."

Atlanta Magazine

"Personalizing the larger story through individual experiences, Blackmon's book opens the eyes and wrenches the gut."

Rocky Mountain News

"For those who think the conversation about race or exploitation in Amer ica is over, they should read Douglas Blackmon's cautionary tale, Slavery by Another Name. It is at once provocative and thought-provoking, sobering and heartrending."

-Jay Winik, author of The Great Upheaval:

America and the Birth of the Modern World, 1788-1800

"A powerful and eye-opening account of a crucial but unremembered chapter of American history. Blackmon's magnificent research paints a devastating picture of the ugly and outrageous practices that kept tens of thousands of Black Americans enslaved until the onset of World War II. Slavery by Another Name is a passionate, highly impressive and hugely important book."

David J. Garrow, author of

Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King Jr.

and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference

"Wall Street Journal Bureau Chief Blackmon gives a groundbreaking and dis turbing account of a sordid chapter in American historythe lease (essen tially the sale) of convicts to commercial interests between the end of the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth."

Publishers Weekly

DOUGLAS A. BLACKMON

S L A V E R Y

BY ANOTHER NAME

Douglas A. Blackmon is the Atlanta Bureau Chief of the Wall Street Journal. He has written extensively on race, the economy, and American society. Reared in the Mississippi Delta, he lives in downtown Atlanta with his wife and children.

www.slaverybyanothername.com

To Michelle, Michael,

and Colette

Slavery:that slow Poison, which is daily contaminating the

Minds & Morals of our People. Every Gentlemen here is born a petty

Tyrant. Practiced in Acts of Despotism & Cruelty, we become callous to

the Dictates of Humanity, & all the finer feelings of the Soul. Taught

to regard a part of our own Species in the most abject & contemptible

Degree below us, we lose that Idea of the dignity of Man which the

Hand of Nature had implanted in us, for great & useful purposes.

GEORGE MASON, JULY 1773

VIRGINIA CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION

CONTENTS

Introduction:

PART ONE:

I.

Fruits of Freedom

II.

"Niggers is cheap."

III.

"Day after day we looked Death in the face & was afraid to speak."

IV.

"The negro dies faster."

PART TWO:

V.

"I don't owe you anything."

VI.

"We shall have to kill a thousand

to get them back to their places."

VII.

"I was whipped nearly every day."

VIII.

"The master treated the slave unmercifully."

IX.

The South Is "an armed camp."

X.

"It is a very rare thing that a negro escapes."

XI.

"Cheap cotton depends on cheap niggers."

XII.

"This great corporation."

PART THREE:

XIII.

A War of Atrocities

XIV.

"Degraded to a plane lower than the brutes."

XV.

"Negro Quietly Swung Up by an Armed Mob All is quiet."

XVI.

"I will murder you if you don't do that work."

XVII.

"In the United States one cannot sell himself."

The Ephemera of Catastrophe

A NOTE ON

LANGUAGE

Periodically throughout this book, there are quotations from individuals who used offensive racial labels. I chose not to sanitize these historical statements but to present the authentic language of the period, whenever documented direct statements are available. I regret any offense or hurt caused by these crude idioms.

INTRODUCTION

The Bricks We Stand On

O n March 30, 1908, Green Cottenham was arrested by the sheriff of Shelby County, Alabama, and charged with "vagrancy"

Cottenham had committed no true crime. Vagrancy the offense of a person not being able to prove at a given moment that he or she is employed, was a new and flimsy concoction dredged up from legal obscurity at the end of the nineteenth century by the state legislatures of Alabama and other southern states. It was capriciously enforced by local sheriffs and constables, adjudicated by mayors and notaries public, recorded haphazardly or not at all in court records, and, most tellingly in a time of massive unemployment among all southern men, was reserved almost exclusively for black men. Cottenham's offense was blackness.

After three days behind bars, twenty-two-year-old Cottenham was found guilty in a swift appearance before the county judge and immediately sentenced to a thirty-day term of hard labor. Unable to pay the array of fees assessed on every prisonerfees to the sheriff, the deputy, the court clerk, the witnessesCottenham's sentence was extended to nearly a year of hard labor.

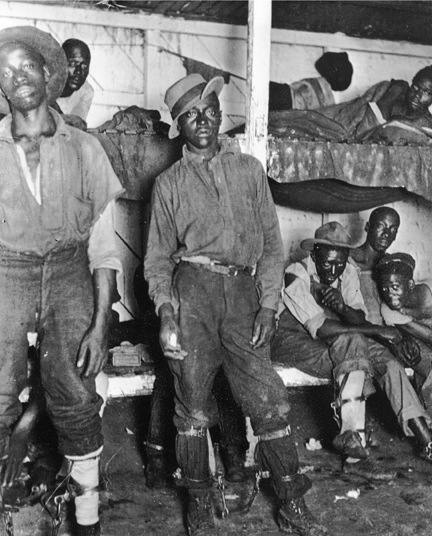

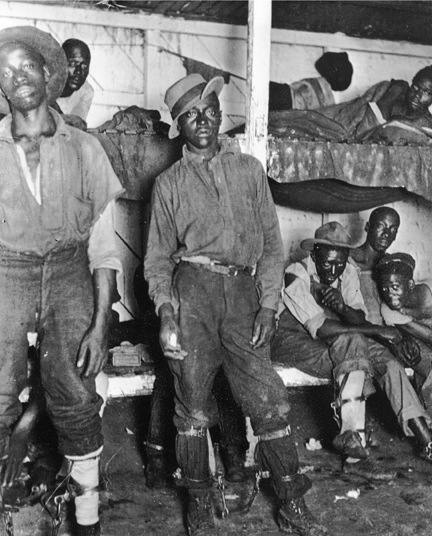

The next day, Cottenham, the youngest of nine children born to former slaves in an adjoining county, was sold. Under a standing arrangement between the county and a vast subsidiary of the industrial titan of the NorthU.S. Steel Corporationthe sheriff turned the young man over to the company for the duration of his sentence. In return, the subsidiary, Tennessee Coal, Iron & Railroad Company, gave the county $12 a month to pay off Cottenham's fine and fees. What the company's managers did with Cottenham, and thousands of other black men they purchased from sheriffs across Alabama, was entirely up to them.

A few hours later, the company plunged Cottenham into the darkness of a mine called Slope No. 12one shaft in a vast subterranean labyrinth on the edge of Birmingham known as the Pratt Mines. There, he was chained inside a long wooden barrack at night and required to spend nearly every waking hour digging and loading coal. His required daily "task" was to remove eight tons of coal from the mine. Cottenham was subject to the whip for failure to dig the requisite amount, at risk of physical torture for disobedience, and vulnerable to the sexual predations of other miners many of whom already had passed years or decades in their own chthonian confinement. The lightless catacombs of black rock, packed with hundreds of desperate men slick with sweat and coated in pulverized coal, must have exceeded any vision of hell a boy born in the countryside of Alabamaeven a child of slavescould have ever imagined.