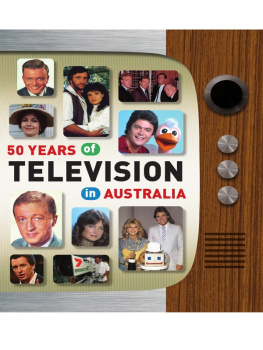

Edited by Nick Place & Michael Roberts

Published in 2006

by Hardie Grant Books

85 High Street

Prahran, Victoria 3181, Australia

www.hardiegrant.com.au

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers and copyright holders.

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Copyright Nick Place and Michael Roberts 2006

Cataloguing-in-Publication Data is available from the National Library of Australia.

Edited by Kerry Biram

Cover and text design by Phil Campbell

Typeset by Phil Campbell and Lisa Stothers

Printed and bound in China by SNP Leefung

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

FEATURES

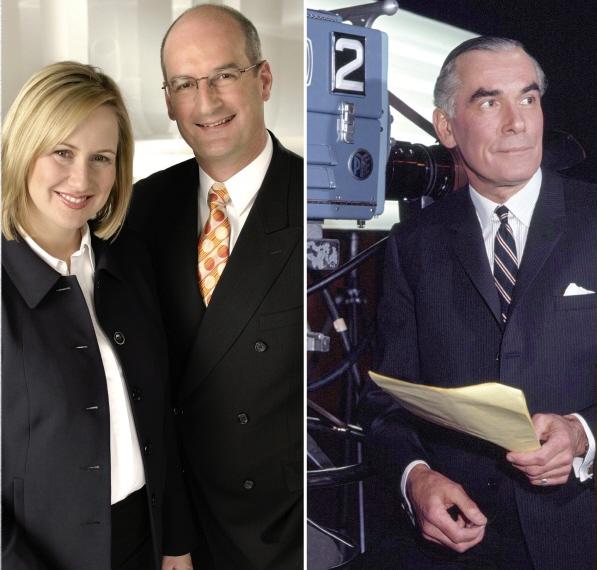

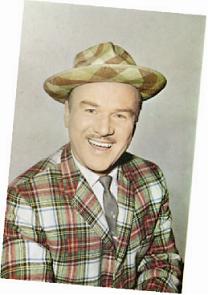

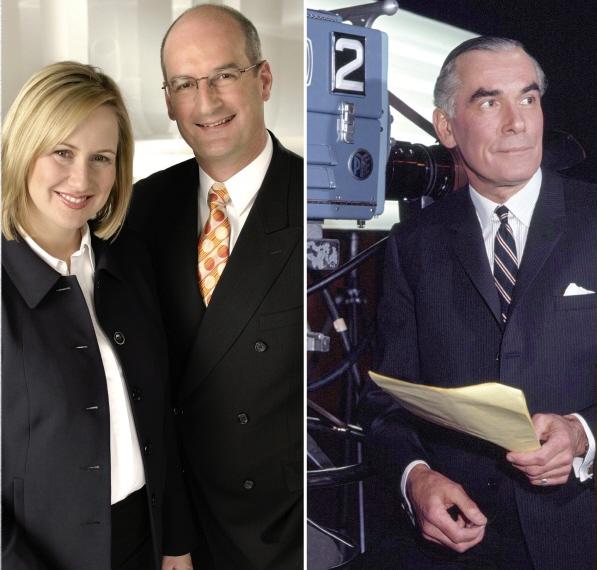

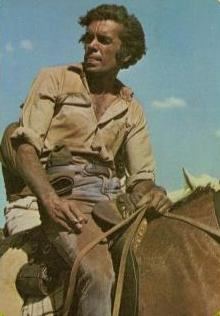

Bruce Gyngell during his staged welcome-to-televisionaddress.

Lets start on 13 July 1956, in Bells Hotel, Woolloomooloo, just near Sydney Harbour. A group of drinkers are gathered around the bar and it would be fair to say they are in a world of wonder that transcends even the alcoholic content of their glasses. These bar flies are watching the first-ever television test transmission in Australian history, as Channel 9, Sydney, experimentally flaps its broadcasting wings.

Three days later, in Melbourne, HSV-7 technicians would cheer as the first-ever signal successfully found its way from the South Melbourne station to Sevens Mount Dandenong receiver and back. Dick Jones was enjoying his first day as a techo in TV and wondered what all the fuss was about. Shortly after, images of a child standing at the Melbourne Shrine of Remembrance would be successfully screened. These technical baby steps all took place less than four months before three Melbourne start-ups planned to cover an Olympic Games.

You have to remember that this was only 27 years after audiences had heard Al Jolson singing in The Jazz Singer and marvelled at sound being added to motion pictures at the theatre. In other words, iPods were a long way away. In 1956, there was no such thing as videotape. If you wanted to tape something, you had to point a 16 mm camera at a blue image of the TV screen received directly from the studio camera. Sound was recorded separately, and had to be matched to the video later.

This is why there is no original footage of the day Australian television began. Bruce Gyngell was the man who famously said: Ladies and gentlemen, good evening and welcome to television at 6.30 pm on TCN-9 on 16 September 1956. He had enough sense of theatre to secretly recreate the moment three years later, when there was a way of filming it for history, but the real thing was transmitted to a few thousand television sets around Sydney, and then disappeared into the ether.

An early Channel 7 Outside Broadcast (OB) van.

If we could see that historic moment, the first thing we might wonder is why its shot at such a strange angle. That was because the Nine studios were still under construction (these were only the beginning of regular, freely available test transmissions the official launch of the station was still more than a month away) and were not ready for the big night, so Gyngell was forced to deliver his line from an engineering storeroom so small the massive camera could barely fit inside the door. Nine was so desperate to be first that such incidentals as a lack of studios simply could not get in the way.

All of which is a long way from mid-1954, poolside at the home of Consolidated Press newspaper tycoon Frank Packer. If ever you wanted a pure display of what makes a media mogul tick, then this is the date to revisit.

After a long and weighty Royal Commission into all matters to do with this newfangled idea of television, which had started on 23 February 1953 and ran for the rest of that year with evidence hearings in most states, Prime Minister Robert Menzies finally announced that bids would be taken for two commercial licences to run stations in Melbourne and Sydney, alongside the governments own intended service, a television version of the Australian Broadcasting Commission.

Around this time, a young radio broadcaster, 24-year-old Bruce Gyngell, was lounging in the sunshine, enjoying a pool party at the home of his mate, Clyde Packer, son of Frank.

Frank Packer came up to me and said, Oh, youre that announcer fellow, arent you? Im applying for a television licence, which Ill probably get, so maybe Ill need people with radio experience, Gyngell recalled in an interview years later. Two things stand out in that remembered conversation. Franks casual confidence which Ill probably get and the fact that his immediate reaction was that hed need some radio talent.

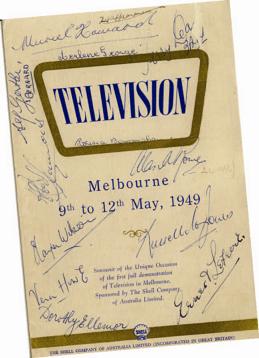

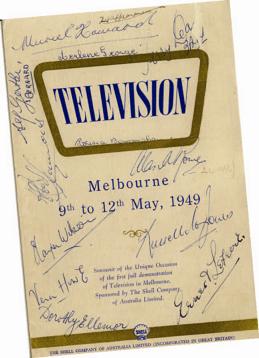

More than seven years before TV officiallybegan, the Shell Company sponsored severaldemonstrations of the new medium in Australia.

Those involved in the start-up of Packers television company never had any doubt about their employers motivation. It was not so much about being a visionary of Frank Packer somehow seeing the glorious and profitable television empire just waiting to unfold. It was about pure fear that television might somehow eat into the companys newspaper profits. So, better to keep the enemy close.

It says a lot about politicians, then and now, that the introduction of television came only after a Canberra-based Royal Commission had fussed and worried over the issue. Professor G.W. Paton, vice-chancellor of Melbourne University, was the chairman, while other members included Mr R.G. Osborne, chairman of the Australian Broadcasting Control Board, Colin Bednall, then a newspaper executive (and later a central figure at GTV-9), and Mrs Maude Foxton, President of the Western Australian branch of the Country Womens Association. Throughout 1953, they listened to 122 witnesses and eventually turned out a 251-page report.

Next page