1956

Nick Richardson is an author, academic, and journalist who has written for a range of publications in England and Australia. He has a PhD in history from the University of Melbourne and is adjunct professor of journalism at La Trobe University. He lives in Melbourne.

Scribe Publications

1820 Edward St, Brunswick, Victoria 3056, Australia

2 John St, Clerkenwell, London, WC1N 2ES, United Kingdom

First published by Scribe 2019

Copyright Nick Richardson 2019

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publishers of this book.

Cover images: Flags shutterstock; 3000m steeplechase Olympic final, 1956 Raymond Morris Collection, National Museum of Australia; Dancers George Marks; Mervyn Wood, source Daily Telegraph ; Robert Menzies National Library of Australia from Canberra, Australia; Olympic torch imagedepotpro; Suez Crisis Tank PA Images/Alamy Stock Photo; Betty Cuthbert INTERFOTO/Alamy Stock Photo; TV CSA Images; ABC logo, source wikimedia commons.

9781925322910 (paperback)

9781925938081 (e-book)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia.

scribepublications.com.au

scribepublications.co.uk

To my mum

Australia is only a young country and we are very proud of our achievements. But we are also fully conscious of our shortcomings.

Victorian Governor Sir Dallas Brooks,

November 1956

The Australians enthusiasm for sport is a consuming passion and it gives him high marks for intelligence. He is smart enough to prefer playing to working: he is jealous of his leisure and he makes use of it.

US sportswriter Red Smith,

December 1956

Contents

Prologue:

Summer 195556

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Autumn 1956

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Winter 1956

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Spring 1956

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Summer 195657

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Preface

One of the hardiest clichs in Australian history is that the 1950s was a dull decade, when conformity settled on the nations shoulders, not to leave until the dynamic 1960s. Yet even the slightest scratching of the historical record reveals that there was significantly more going on than this clich would have us believe. The decade was distinguished by drama, innovation, social change, a loosening of British ties, a big boost in migration, and the rise of consumerism. Australia was already on the path to being a different country by the time 1960 arrived. And the pivotal year in the preceding decade was 1956, when a series of important events some accidental, others years in the planning were critical in shaping the nation.

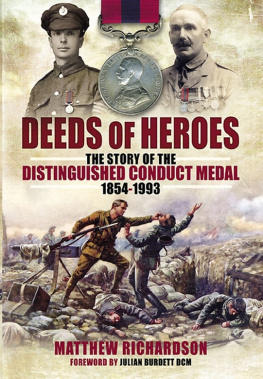

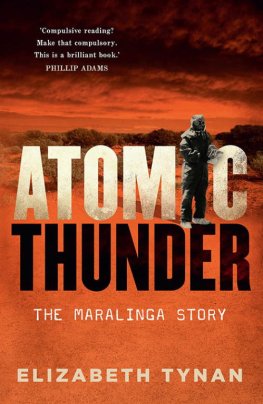

Most people will nominate the Olympic Games in Melbourne and the arrival of television as the nations best-known moments of the year, but, as important as these were, there were other events that revealed something else about Australia. There were the British atomic tests at Maralinga, the arrival of the Hungarian refugees in Sydney after the bloody uprising against Soviet rule, the success of Summer of the Seventeenth Doll , and the emergence of Barry Humphries comic creation Edna Everage. While Prime Minister Robert Menzies capitalised electorally on the split in the Labor opposition, he also walked the international stage, trying to solve the impasse at the heart of the Suez Canal crisis. These were all elements contributing to a shifting perspective on Australias place in the world how we saw ourselves and how other nations saw us.

How Menzies government handled Maralinga said much about our attitude to Indigenous Australians. How we embraced The Doll told us something about our cultural tastes and our desire to hear our own voices on stage. Our response to the Hungarian refugees affirmed our capacity to absorb others into what was an evolving multicultural society before the word was commonplace. And all of this was occurring during one of the most charged eras in world history, when the Cold War gave rise to suspicion and paranoia that inevitably spread to Australia. This is why the stakes were so high for many of the international events of 1956, and Australias proximity to some of those events brought it to the worlds attention.

There were subtle but distinct conflicts occurring across Australia by 1956: the rise of the energetic modernisers, who had a vision for the nation that elevated it to the international stage, and those who saw Australia as part of the Empires rich continuum, stable and safe. There was also, in the broadest definitions of the word, the conflict between the amateurs, those who believed in the happy accident of talent, and those professionals who saw the need for not only talent but also an organised and intelligent approach to sport, business, and the arts. And then there were those who felt that regulation and control was the right way for Australian society to proceed in an uncertain world, while some others saw the alternative as a means of freedom and a mark of maturity. All of them were caught up in the events of 1956.

This book has identified several characters who were part of the years events. In some instances they were not the main figures but their story helps illuminate the bigger picture. They move in and out of focus as the year progresses, commenting on their circumstance, telling us how they got there and, in some cases, what happened next. The books structure follows the chronology of the year, and culminates inevitably with the Olympic Games in Melbourne. The Games crystallised some of those shifts in Australian life, and underlined how the nation was in the worlds sight like never before. This is a book about a year when Australias gaze was pulled outwards, beyond the Empire and the old world, and towards a different future.

Prologue

April 1949

The Pan Am aeroplane touched down at Honolulu airport at 11.20 pm on Friday 14 April 1949. On board was a neat, spare 72-year-old Japanese man who was embarking on a mission that required a unique set of skills: diplomacy, discretion, patience, and the detachment, or perhaps imagination, to put international opprobrium to one side. Matsuzo Nagai was on his way to Rome to lobby the International Olympic Committee to re-admit Japan to the Olympic movement. World War II had ended less than four years earlier, and under the terms of the peace Japan was still under US occupation.

Dr Nagai was a long-term and ardent advocate of Japans return to the Olympic family. Before the war, he had been in charge of Tokyos bid for the 1940 Olympics; it took Japans war with China to end that dream. When the Games resumed in London after World War II, Japan and Germany were excluded, but later in 1948 Japan started organising itself for another tilt at hosting the Games. Dr Nagai told waiting reporters at Honolulu airport that he had been encouraged by a message from IOC vice president Avery Brundage that Japans application to rejoin the Olympic movement might be received favourably. And General Douglas MacArthur, running the Allied occupation of Japan, had sanctioned the nations participation in sports so why not the Olympics, the greatest sporting competition in the world? The time, Dr Nagai argued, was right for Japan to come in from the Olympic cold. I believe that through the medium of sports, nations can be brought closer to one another and a better spirit of understanding and friendship can be developed, he said.

Next page