Pagebreaks of the print version

SUEZ CRISIS 1956

END OF EMPIRE AND THE RESHAPING OF THE MIDDLE EAST

DAVID CHARLWOOD

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by

PEN AND SWORD MILITARY

an imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire S70 2AS

Copyright David Charlwood, 2019

ISBN 978 1 52675 708 1

eISBN 978 1 526 75 709 8

Mobi ISBN 978 1 526 75 710 4

The right of David Charlwood to be identified as the author of this work

has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or

mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system,

without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders of material reproduced in this book,

but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to hear from them.

Front cover image: A Westland Whirlwind helicopter taking off from HMS Albion

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword

Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military,

Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Social History, Transport, True Crime, Claymore Press, Frontline

Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen and Sword titles please contact

Pen and Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

email:

website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

or

Pen and Sword Books

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

email:

www.penandswordbooks.com

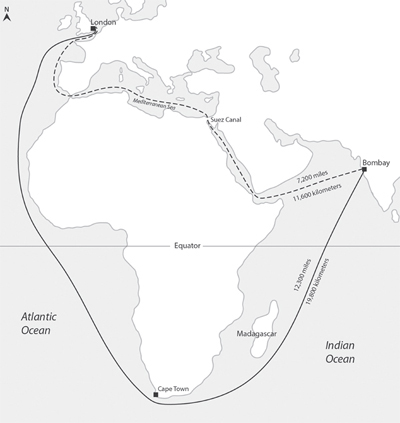

The two LondonBombay sea route options.

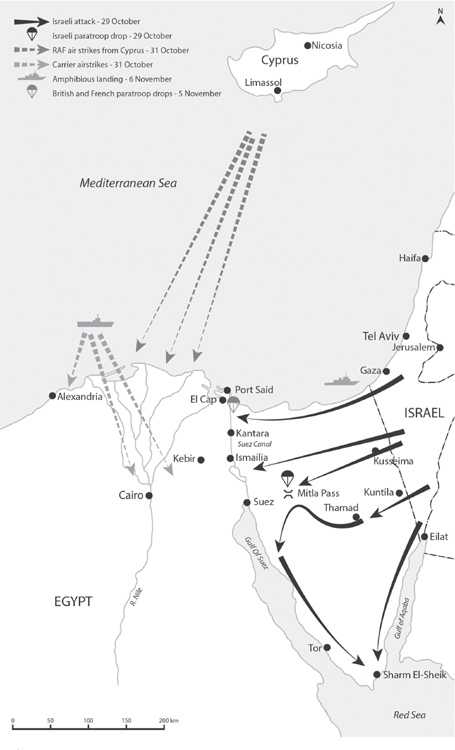

The Suez operation.

TIMELINE

| 1955 |

| September | Nasser agrees arms deal with Czechoslovakia for Soviet-made weaponry |

| 21 November | U.S., Britain and Egypt begin discussions over financing for the Aswan Dam |

| 1956 |

| 13 June | Last British forces depart from Suez Canal Base in line with the 1954 Anglo-Egyptian Treaty |

| 19 July | U.S. Secretary of State Dulles informs the Egyptian ambassador that U.S. will not fund construction of the Aswan Dam |

| 26 July | Nasser nationalizes the Suez Canal |

| 12 August | Nasser rejects invitation to attend the London conference |

| 18 August | Start of the Conference of London |

| 5 September | Nasser rejects Menzies proposals of internationalization of the Suez Canal |

| 15 September | European pilots leave the Suez Canal. Egypt maintains traffic using Egyptian, Russian and Indian pilots |

| 19 September | Start of second London conference to discuss American proposal for Suez Canal Users Association (SCUA) |

| 513 October | UN Security Council debates Suez Crisis |

| 14 October | Eden meets French representatives at Chequers who present the plan to use Israeli invasion as pretext for attack |

| 24 October | Britain, France and Israel sign Svres Protocol |

| 29 October | Israeli forces attack Egypt |

| 30 October | British and French issue ultimatum to Egypt and Israel |

| 31 October | Royal Air Force begins bombing of Egyptian targets |

| 5 November | French and British airborne troops land at Port Said |

| 6 November | British and French amphibious forces land at Port Said and that evening Eden agrees ceasefire; Eisenhower wins re-election |

| 7 November | Eisenhower messages Ben-Gurion demanding withdrawal of Israeli forces |

| 3 December | Lloyd announces intention to withdraw all British forces from Suez. |

| 20 December | Eden states in Parliament that he had no foreknowledge of the Israeli attack on Egypt |

| 23 December | Last British and French troops leave Suez |

| 1957 |

| 5 January | Eisenhower presents the Eisenhower Doctrine to U.S. Congress |

| 9 January | Eden resigns as prime minister |

| 13 March | Jordan pulls out of Anglo-Jordanian Treaty |

| 8 April | Suez Canal reopens |

| 13 July | Suez Canal Company reaches compensation agreement with Egyptian government |

The entrance to the canal at Port Said, 1869.

PROLOGUE

On Christmas Eve 1798, Napoleon Bonaparte stared out across the sea of sand between Cairo and Suez. Frances most famous general carried with him an order to begin an engineering project to open up new trade routes in the East. He was simply instructed to arrange for the cutting of the Isthmus of Suez.

The idea of carving a path through the strip of land that separated the Mediterranean and the Red Sea had been dreamed of as far back as the Pharaohs, but would consume the sleepless nights of emperors and engineers for another seventy years before it was finally completed at a cost of hundreds of thousands of lives and millions of dollars. The plaudits for the creation of the canal went to another Frenchman: Ferdinand de Lesseps.

De Lesseps was a bushy-moustached and indefatigable career diplomat who only began trying to build a canal after he had officially retired. He had no engineering qualifications. He did, however, have a diplomats ability to win friends and influence people, including Said Pasha, who ruled Egypt as viceroy, nominally under the auspices of the Ottoman sultan. De Lesseps returned to his old diplomatic haunt in 1854 and convinced Said Pasha to back the scheme by appealing to his sense of ego: What a fine claim to glory! For Egypt, what an imperishable source of riches! Somewhat inaccurately he added, The names of those Egyptian sovereigns who built the pyramids are forgotten. The name of the Prince who opens the great maritime canal will be blessed from century to century until the end of time. Said Pasha agreed and granted a concession to the newly created Compagnie universelle du canal maritime de Suez to control the planned waterway for ninety-nine years following construction, after which time ownership would revert to the Egyptian government. With the concession agreed, de Lesseps went off to find financial backers.

Ferdinand de Lesseps.

The concept was a potentially lucrative one. By cutting a canal between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea, vessels travelling between Europe and Asia would no longer have to sail around the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa and whoever was part of the concession would get a cut of the fee every vessel transiting the canal would be required to pay. The problem was not one of potential profit, however, but one of practicalities. Even though de Lesseps had the backing of a team of experienced engineers, it would still be a herculean task. Selling the project was not helped by the fact that Napoleons own engineers, when they had investigated the potential of a canal in the late eighteenth century, had wrongly calculated that the Red Sea was ten metres higher than the Mediterranean and that cutting a path between the two would result in catastrophic flooding across the Nile Delta and the manmade river becoming a raging, unnavigable torrent. Even though de Lessepss engineers were right and Napoleons wrong, it was hard to cast aside the notion that the scheme was liable to failure, but the British objections were primarily over security. Britannia ruled the waves in the nineteenth century and even though relations with France were cordial, the British in particular did not trust the French; as one minister told de Lesseps, in the event of war with France both ends of the canal would be closed to Britain and it would be a suicidal act on the part of England to support the venture.