THE

SUEZ WAR

PAUL JOHNSON

For copyright reasons, any images not belonging to the original author have been removed from this book. The text has not been changed, and may still contain references to missing images.

This electronic edition published in 2014 by Bloomsbury Reader

Bloomsbury Reader is a division of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 50 Bedford Square,

London WC1B 3DP

First published in Great Britain in 1957 by MacGibbon & Kee

Copyright 1957 Paul Johnson

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

The moral right of the author is asserted.

eISBN: 9781448214655

Visit www.bloomsburyreader.com to find out more about our authors and their books You will find extracts, author interviews, author events and you can sign up for newsletters to be the first to hear about our latest releases and special offers.

THIS BOOK IS

DEDICATED TO

MARIGOLD

Contents

Chapter 1

Prelude to Catastrophe

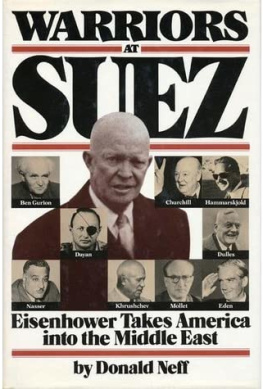

On the afternoon of Thursday July 19 1956, Mr John Foster Dulles, the American Secretary of State, asked the Egyptian Ambassador in Washington, Mr Ahmed Hussein, to come to his office in the State Department. When the Ambassador arrived, Mr Dulles handed him a letter, in which the United States Government announced the withdrawal of its offer to contribute $56 million towards the financing of the Egyptian High Dam at Aswan. Pale with anger, Mr Hussein hurried back to his embassy to telephone the news to his Foreign Minister, Dr Fawzi, in Cairo. He was too late; Fawzi already knew. Contrary to diplomatic practice, Mr Dulles had communicated the statement to the Press before delivering it to the country concerned.

The next morning, Sir Harold Caccia, Acting Permanent Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office, informed Mr Abdul Fetouh, the Egyptian Ambassador in London, that Britain too was withdrawing its loana matter of $15 million. The same evening, Mr Eugene Black, President of the World Bank, announced that, owing to the Anglo-American action, the World Bank was no longer in a position to advance the $200 million which it had promised Egypt the week before.

In his letter, Mr Dulles said the reasons for Americas withdrawal were Egypts failure to agree to various amendments to the plan for the dam, and doubts as to her ability to provide the sum of $700 million, which was to be her eventual share of its cost. On the first point, the letter was misleading: the American conditions had been stated in an aide-mmoire sent to Egypt in December; most of these had been accepted by Egypt in January, and only a week before the U.S. withdrawal the Egyptian Ambassador had returned to Washington from Cairo with instructions to accept the remaining ones.

On the second point, the letter was nearer to the mark. In the past ten months, Egypt had been buying ever-increasing shipments of arms from behind the Iron Curtain. In April, it was learned that she had mortgaged $200 million of cottonas yet unplantedin exchange for Czech-produced MIG 15s and 17s, and Stalin heavy tanks. On July 9, publication of the Egyptian budget revealed that military expenditure was to rise from 18 to 25 per cent of total appropriations. During 1957, it showed, Egypt would spend E54 million on arms and only E2.9 million on the dam. Egypt, it was clear to the State Department economic experts, must inevitably fall behind on its payments towards the project. But this fact, strangely enough, had not caused misgivings in the World Bank. On the contrary, on July 12 the Bank had come to a provisional agreement with Mr Hussein, which was awaiting signature when Mr Dulles made his announcement.

What, then, were the real reasons for Americas withdrawal? There were two. First, Mr Dulles was under severe pressure from Congress to cut foreign aid appropriations. The Senate, anxious to finish the business for the session and escape from the syrupy heat of Washington, was in an ugly mood. The week before, its Appropriations Committee had asked Dulles to abandon the Aswan project. He had refusedhesitantly. Then, on July 17, representatives of the Senate cotton lobby, which naturally wished to prevent the increase in Egyptian cotton production which the dam project would eventually facilitate, called on him and extracted from him the promise that he would reconsider the matter.

The fact was, Dulles was movingin his usual haphazard and unsystematic mannertowards a major policy decision. Ever since the war, America had supported Egypt, both as a counter to British colonialism in the Middle East and as a proof of its friendship for the up-and-coming nations of Asia and Africa. The U.S. Ambassador in Cairo, Charles Byroade, was a fervent Egyptophile and well disposed to the Nasser rgime. He was moreover, fully backed up by his chief in the State Department, Mr George Allen, in charge of the Middle Eastern desk. Allen, who disliked colonialism, was instrumental in preventing America from joining the British-sponsored Baghdad Pact, and in forging firm bonds of friendship with Saudi Arabia, Britains traditional enemy on the Persian Gulf. Together, these two men had succeeded in making support for Nasser the linchpin of Americas Middle Eastern policy.

But for some months before that fatal Thursday afternoon, Dulles had been eyeing Nasser with increasing dislike. Nassers decision, in September 1955, to buy Communist arms had allowed Russia, in one move, to leap over Britains ramshackle Northern Tier and to become, for the first time in her history, an effective Middle Eastern Power. Dulles disliked seeing MIG 15s unloading in Alexandria. He disliked even more hearing that the Russian Embassy in Cairo had increased its staff from forty to 150, and that Russian technicians were pouring into Egypt. He disliked also being prodded and nagged at by the British for backing Nasser. He disliked too the increasing improvidence and rapacity of Nassers Saudi Arabian allies, who were already two years overdrawn on their oil revenues, and who had, in May, suddenly decided to increase the rent payable for the American atomic bomber base at Daihran. Dulles had been brooding on these grievances for some time. But what finally made him change his mind was the news that Nasser was to take part in a meeting on the Yugoslav island of Brioni with Nehru and Tito. It was, the Press announced, a conference of the neutralist Powers, and it was taking place without Dulles consent or encouragement. He read the papers, crowded with photographs of the Brioni junketings, with increasing irritation. Within a few days, he had come to a decision, and his first act was to replace Byroade in Cairo and transfer Allen.

To the well informed, this was a clear portent of things to come, and the London Times made the changes its main lead-story the next day. But after seeing the cotton lobby men, Dulles decided it would be convenient to make the warning to Nasser even more explicit. The same afternoon he telephoned the President to get his agreement to scrap the Aswan project. Eisenhower, who was playing golf, and whose interest in the dam was, to say the least, dispassionate, told Dulles to go ahead. So the die was cast, and the first step taken towards the Suez catastrophe.

Next page