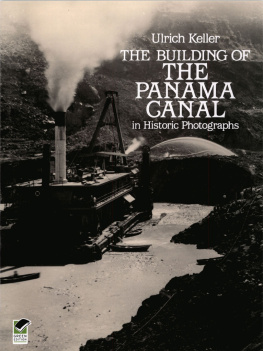

For a week, the vessels had been sailing into Port Said, Egypts newest harbor, which lay on the Mediterranean side of the Isthmus of Suez. On this day, it was crowded with ships - nearly eighty of them riding at anchor in the calm water of the roadstead.

Some were yachts, some were merchant vessels, and some were men of war, all freshly decorated and painted for the occasion. Colorful pennants streamed from every mast, and the decks were lined with sailors in dress uniform. The flags of almost all the seafaring nations of the world fluttered in the light sea breeze. It was a clear, sparkling day under an intense blue sky.

At the front of the great flotilla rode a sleek black yacht that flew the colors of France. A few minutes before eight oclock on this morning - Wednesday, November 17, 1869 - a beautiful woman appeared on the bridge of the yacht; with her was an older man in a black frock coat. Along the breakwaters and all around the curve of the harbor, the crowd began to cheer. At the same time, cannons sounded from shore batteries and from all the warships lying at anchor. The stately woman smiled and waved her handkerchief, and the crowd roared again.

She was Empress Eugnie of France, who had been invited by the Khedive Ismail, ruler of Egypt, to be the guest of honor at the opening of the new Suez Canal. The man with her was her cousin, Ferdinand de Lesseps, who had developed the idea of the canal and built it - against great odds. The canal was a reality at last, and this inaugural celebration promised to be one of the most splendid events of the nineteenth century.

Shielding her eyes against the bright Egyptian sun, Eugnie looked toward the shore. The cannons continued to fire, and the harbor was filling with smoke. But she could still make out the excited crowd.

There were Egyptian workers and soldiers, Bedouins and Turkish noblemen. There were Greek sailors and French engineers, merchants from Syria and veiled Tuaregs from the desert. There were black men from the Sudan and white men from all the countries of Europe. Some had even come from Russia and the faraway Americas. Now they were crowded together around the harbor of Port Said, all anxious for a place near the waters edge. The great celebration was about to begin.

Eugnies eyes sparkled. When she had left Marseilles almost two months earlier, she had not imagined that she would be sailing into an adventure out of The Arabian Nights.

But, during her journey, she ate strange foods and saw strange sights and heard strange sounds. She dined at Constantinople with the sultan of Turkey and his grand vizier. She lunched at a palace near the Great Pyramids with the Khedive himself. She saw Arab horsemen and Turkish lancers and savage tribesmen from the Congo. And she heard the cries of the bazaar and the Muslim prayers at sunset. Now, at last, she was beginning the most exciting part of her adventure. In a few minutes, she would lead all the ships at Port Said through the magnificent new canal. For the next few days, she would be at the center of all the mystery, magic, and glamor of the Middle East.

Just before eight oclock, an unexpected silence fell over the harbor. The cannons stopped firing, and the crowd no longer cheered. There was only the faint cry of a seagull; the clearest sound de Lesseps and the Empress could hear was the creaking of an anchor chain being raised. They nodded silently to each other, and de Lesseps took a watch from his pocket. The hands pointed to eight oclock.

Then the silence in the harbor came to a sudden end. The air was filled with the hissing of steam whistles and the wailing of sirens. The cannons sounded again and again, and the crowd cheered with wilder excitement than before. Sailors shouted from the yardarms, and on the warships, naval bands began to play. The stirring sound of military music filled the harbor.

With deafening blasts from her siren, lAigle, the yacht that carried de Lesseps and the Empress, started up. The ships paddle wheels churned the harbor water; then she moved ahead, veered slightly, and straightened out in order to enter the canal head on. The bands were playing a French military air called Partant pour la Syrie (Leaving for Syria) as the yacht passed through the entrance to the Suez Canal.

The incredible journey had begun. In front of the flotilla lay the 100 miles of silent desert of the Isthmus of Suez. But the desert had been conquered now, and the way was clear to the town of Suez itself - the new door that led to India and the riches of the Far East.

At fifteen-minute intervals during the day, most of the other ships in the harbor entered the canal. They kept their speed to five knots an hour, and the distance between them was three-quarters of a mile. In single file behind Eugnies yacht came the Greif, which carried Emperor Franz Josef of Austria-Hungary and his party, a frigate with the Crown Prince of Prussia, and at the appropriate interval, a Dutch yacht with the Prince and Princess of Holland on board. They were in turn followed by a Russian ship with the Grand Duke Michael and General Ignatiev, who came as representatives of the czar. The Psyche steamed by, and at the railing was the British ambassador to Constantinople. One after another nearly fifty of the ships in the harbor turned into the Suez Canal. Not since the days of the pharaohs had so much activity been seen on this barren isthmus in a remote corner of Egypt.

The day passed, and lAigle steamed slowly through the canal at the head of the great international procession. The desert was astonishingly beautiful. A British colonel, watching from the deck of one of the merchant ships, said later that it was an enchanted scene. And surely it must have seemed like some fantastic mirage, with silent ships floating on the desert and white-robed Bedouins watching from the banks of the canal.

By five in the afternoon, less than ten hours after leaving Port Said, the first ships were approaching Ismailia. Just before six oclock in the evening, the yacht carrying de Lesseps and the Empress steamed into Lake Timsah.

This lake forms a perfect natural harbor, and while the canal was being dug, workmen had built a handsome town on the lakes northwest shore. They called it Ismailia in honor of the Khedive of Egypt. It marked the approximate half-way point between Port Said on the Mediterranean and Suez on a gulf of the Red Sea and was an ideal place to regroup and prepare for the rest of the journey.

More than this, Ismailia was an ideal place for the Khedive Ismail to give a party. He had turned his namesake into an elaborate stage setting of Eastern splendor. It was a fairyland of flowers and lights and ornate buildings that might have come from the pages of an Oriental adventure story. The Khedive was a grandiose ruler who loved nothing better than luxury and ostentation. This was the great moment of his life, his chance for immortality, and he spared no expense on the decoration of Ismailia. The cost of his fabulous party, in fact, came to some $7.5 million. On Wednesday night, while his guests slept on their yachts in the harbor, the Khedive roamed the many rooms of his magnificent palace, arranging the last details of the next days festivities. All through the night, torches flickered along the docks and in the streets of Ismailia, and the lights in the palace burned until dawn.

On Thursday morning, November 18, the good weather held, and the sky was bright and clear once again. The harbor of Ismailia presented an even more vivid spectacle than Port Said had the day before. All along the shore, flagpoles had been set up, and the banners of crimson and gold - some with crosses and others with Muslim crescents - furled and unfurled in the soft breeze. The Khedives palace, gleaming in the sunlight, stood near the lake and dominated the town. There were flowers everywhere and triumphal arches and green trees. Early in the morning, the warships began firing their cannons, and the sirens and the whistles began again. The harbor, like Port Said, was a sea of masts, flags, and drifting smoke.