Multiple transliterations exist of Russian, Chinese, Arabic, Hebrew, Persian, and other place and personal names. Gamal Abdel Nasser may be written as Gamal Abd el-Nasr, Gamal abd-an-Nasir, and further variations. It is Jamal Abdul Nassir in some texts, though Jamal is misleading for English speakers: the Arabic letter jm (), pronounced like an English j by many Arabic speakers, is pronounced in Egypt as a hard g (as in get). Places in Israel or the Palestinian territories often have different transliterations reflecting usage in Arabic and Hebrew: Qibya/Kibbiya, Kafr Qasim/Kfar Kassem.

It is impossible to be entirely consistent, so the transliterations most common in 1956 English-language sources have been preferred. Some of these have now fallen out of usefor instance, Peking is now universally known as Beijing. It is hoped that the forms used, even if outdated, reflect the tone of the time and are more consistent with the sources quoted. Where quotes use a different spelling, it has not been changed.

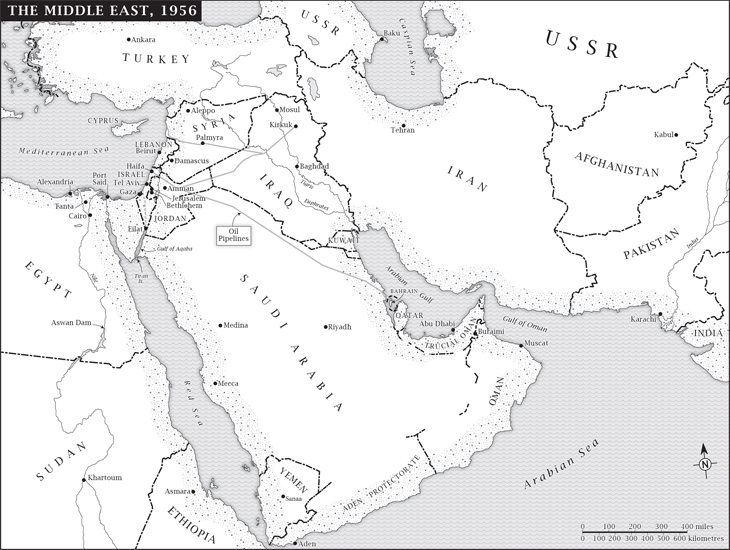

The Arabs and Arab world referred to in this book are defined as they commonly were in 1956, though many people living in those areas then and now are not Arabs. The Arab world was broadly defined linguistically but formed a diverse cultural and political entity. It included the Arabic-speaking territories of North Africa and the Middle East. Iran and Turkey, where Persian (Farsi) and Turkish are spoken respectively, are not and were not Arab, though they do comprise part of the Middle East. Pakistan is neither Arab nor part of the Middle East, but joined the regional defense alliance known as the Baghdad Pact along with Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and the United Kingdom.

Hungarian names are written with the surname before the first name: Nagy Imre rather than Imre Nagy. When writing in English, Hungarians usually reverse this to conform with Western conventions. This book follows their lead.

When researching a book that covers history one day at a time, it soon becomes clear that sources disagree on the precise dates and times of events. Wherever possible, the dates given in this book have been verified with archival documents and daily newspapers, but sometimes different witnesses have conflicting memories that are impossible to resolve.

March 1956 // Savoy Hotel // London, United Kingdom

It had been a busy Monday for Anthony Nutting. As part of his ministerial duties at the British Foreign Office, he had completed a plan for a United Nations police force takeover of British military positions on Israels border. At the same time, Britain would increase military and ecaonomic aid to its Arab allies.

As the spring day shaded into evening, Nutting left his Whitehall office for the more sumptuous surroundings of the Savoy Hotel on the north bank of the Thames. He was to dine with a visiting American member of the United Nations disarmament commission.

Halfway through dinner, they were interrupted. Nutting was told there was an urgent telephone call for him on the hotel switchboard. He excused himself. Out of earshot, he took the call.

Its me, said the agitated voice at the other end. Whats all this poppycock youve sent me? I dont agree with a single word of it.

Caught flat-footed, Nutting explained that the plan he had submitted earlier that day was designed to rationalize Britains position in the Middle East. The aim was to reduce the influence of Gamal Abdel Nasser, the president of Egypt and the most irritating of all the thorns in the British side.

But whats all this nonsense about isolating Nasser or neutralising him, as you call it? shouted the voice. I want him murdered, cant you understand?

The threat shocked Nutting, but he kept his cool. Nasser could not be removed, he said, unless a preferable alternative were ready to replace him. Otherwise, Egypt might descend into anarchy.

But I dont want an alternative. And I dont give a damn if theres anarchy and chaos in Egypt, snarled the voice, which belonged to the prime minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. There was a click on the line, then silence. Sir Anthony Eden had hung up.

July 26, 1956 // Alexandria, Egypt

The thermometer hit 110 Fahrenheit as Gamal Abdel Nasser stepped up to speak in Alexandrias Mansheya Square. He was thirty-eight years old, broad-shouldered, confident, and ambitious. Since the beginning of the decade, he had been a rising star in Egypts military. He had won important admirersmost notably inside the American Central Intelligence Agency (CIA)s operation in Egypt. Nasser made it clear he was open to American overturespotentially to the cost of Britains longs-tanding influence in Egypt: America can win our friendship by acting in accordance with the principles of the American liberation revolution, he said.

Nasser had already overthrown a king and a president. He had been behind the dethroning of King Farouk in 1952. He had ousted Farouks successor, President Mohamed Neguib, in 1954. This was not a man who would quail at taking on an empire, or even two.

In another age, Nasser could have been the sort of Arab leader favored by the West. He was pro-American, anti-Communist, and secular, yet blessed with almost unlimited credibility throughout the Middle East. He was, according to one CIA agent, a magnificent-looking man, witty and personable, with an excellent command of English. He was fiercely opposed to Israel, but so were all Arab leaders; the CIA believed he had more potential for making peace than most of them. Though Egypt and Israel had engaged in an arms race against each other, he had consistently tried to avoid open war. With American encouragement, he had even allowed secret channels for communication to open between Cairo and Tel Aviv. He could be ruthless with his own people, but much of his ruthlessness was directed toward fighting the Muslim Brotherhoodwhose leading ideologue, Sayyid Qutb, would go on to become the intellectual father of al-Qaeda. Less than two years earlier, Nasser had been speaking on the same spot in Mansheya Square when a Muslim Brother had slipped through the crowd and, from a distance of just twenty-five feet, fired eight shots at him. All eight had missed. Nasser had enhanced his public image by appearing unruffled.

The estimated quarter of a million people filling the elegant park of Mansheya Square on July 26, 1956, were crammed in under the palm trees between neoclassical facades leading down to the Mediterranean Sea. Nassers speech was broadcast over his Voice of the Arabs radio station to listeners throughout the Arab world and was simultaneously translated into English and French for those farther afield. For half an hour, he described imperialist crimes committed over the centuries by Britain and France, andin a comic, knockabout style that the crowd enjoyedhis own recent negotiations with Eugene Black, the president of the World Bank. Mr. Black suddenly reminded me of Ferdinand de Lesseps, he said. He seemed to get stuck on this theme, and conspicuously mentioned the name several more times. De Lesseps, he kept repeating. De Lesseps.