CONTENTS

PART I

Two Men and a Ladder

PART II

Vermeer and the Irish Gangster

PART III

The Man from the Getty

PART IV

The Undercover Game

PART V

In the Basement

JUNE 2004

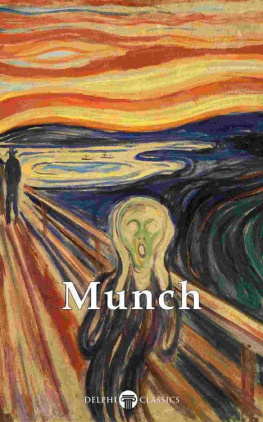

T he mismatched pictures stare down from the wall of the tiny office: Vermeer, Goya, Titian, Munch, Rembrandt. Ordinary reproductions worth only a few dollars, they are unframed and of different sizes. Several dangle slightly askew from tacks jammed in the wall. The originals hung in gilt frames in the grandest museums in the world, and tourists made pilgrimages to see them. Each was worth millions, or tens of millions.

And, at some point in the last several years, each was stolen. Some were recoveredthe tall man who arranged this small display is the one who found themand some are still missing. The curator of this odd collection dislikes anything that smacks of statistics, but he is haunted by a melancholy fact: nine out of ten stolen paintings disappear forever.

In the world of art crime, one detective has an unmatched rsum. His name is Charley Hill. The aim of this book is to explore the art underworld; Hill will serve as our guide. It is odd and unfamiliar territory, dangerous one moment, ludicrous the next, and sometimes both at once.

We will look at many tales of stolen paintings along the way in order to learn something of the territory in general, but the story of one world-famous workThe Scream, by Edvard Munchwill serve as the thread we follow through the labyrinth. A decade ago, Hill had no more connection with that painting than did any of the millions who recognized it instantly from reproductions and cartoons.

On the morning of February 14, 1994, a phone call changed all that.

PART I

Two Men and a Ladder

1

Break-in

OSLO, NORWAY

FEBRUARY 12, 1994 6:29 A.M .

I n the predawn gloom of a Norwegian winter morning, two men in a stolen car pulled to a halt in front of the National Gallery, Norways preeminent art museum. They left the engine running and raced across the snow. Behind the bushes along the museums front wall they found the ladder they had stashed away earlier that night. Silently, they leaned the ladder against the wall.

A guard inside the museum, his rounds finished, basked in the warmth of the basement security room. He had paperwork to take care of, which was a bore, but at least he was done patrolling the museum, inside and out, on a night when the temperature had fallen to fifteen degrees. He had taken the job only seven weeks before.

The guard took up his stack of memos grudgingly, like a student turning to his homework. In front of his desk stood a bank of eighteen closed-circuit television monitors. One screen suddenly flickered with life. The black-and-white picture was shadowythe sun would not rise for another ninety minutesbut the essentials were clear enough. A man bundled in a parka stood at the foot of a ladder, holding it steady in his gloved hands. His companion had already begun to climb. The guard struggled through his paperwork, oblivious to the television monitors.

The top of the ladder rested on a sill just beneath a tall window on the second floor of the museum. Behind that window was an exhibit celebrating the work of Norways greatest artist, Edvard Munch. Fifty-six of Munchs paintings lined the walls. Fifty-five of them would be unfamiliar to anyone but an art student. One was known around the world, an icon as instantly recognizable as the Mona Lisa or van Goghs Starry Night. In poster form, it hung in countless dorm rooms and office cubicles; it featured endlessly in cartoons and on T-shirts and greeting cards. This was The Scream.

The man on the ladder made it to within a rung or two of the top, lost his balance, and crashed to the ground. He staggered to his feet and stumbled back toward the ladder. The guard sat in his basement bunker unaware of the commotion outside. This time the intruder made it up the ladder. He smashed the window with a hammer, knocked a few stubborn shards of glass out of the way, and climbed into the museum. An alarm sounded. In his bunker, the guard cursed the false alarm. He walked past the array of television screens without noticing the lone monitor that showed the thieves, stepped over to the control panel, and set the alarm back to zero.

The thief turned to The Screamit hung only a yard from the windowand snipped the wire that held it to the wall. The Scream, at roughly two feet by three feet, was big and bulky. With an ornate frame and sheets of protective glass both front and back, it was heavy, tooa difficult load to carry out a window and down a slippery metal ladder. The thief leaned out the window as far as he could and placed the painting on the ladder. Catch! he whispered, and then, like a parent sending his toddler down a steep hill on a sled, he let go.

His companion on the ground, straining upward, caught the sliding painting. The two men ran to their car, tucked their precious cargo into the back seat, and roared off. Elapsed time inside the museum: fifty seconds. In less than a minute the thieves had gained possession of a painting valued at $72 million.

It had been absurdly easy. Organized crime, Norwegian style, a Scotland Yard detective would later marvel. Two men and a ladder!

At 6:37 A.M . a gust of wind whipped into the dark museum and set the curtains at the broken window dancing. A motion detector triggered a second alarm. This time the guard, 24-year-old Geir Berntsen, decided that something was wrong. Panicky and befuddled, he thrashed about trying to sort out what to do. Check things out himself? Call the police? Berntsen still had not noticed the crucial television monitor, which now displayed a ladder standing unattended against the museums front wall. Nor had he realized that the alarm had come from room 10, where The Scream hung.

Berntsen phoned his supervisor, who was at home in bed and half-asleep, and blurted out his incoherent story. In midtale, yet another alarm sounded. It was 6:46 A.M . Fully awake now, Berntsens supervisor hollered at him to call the police and check the monitors. At almost precisely the same moment, a police car making a routine patrol through Oslos empty streets happened to draw near the National Gallery. A glance told the tale: a dark night, a ladder, a shattered window.

The police car skidded to a stop. One cop radioed in the break-in, and two others ran toward the museum. The first man to the ladder scrambled his way to the top, and then, like his thief counterpart a few minutes before, slipped and fell off.

Back to the radio. The police needed another patrol car, to bring their colleague to the emergency room. Then they ran into the museum, this time by way of the stairs.

The policemen hurried to the room with the ladder on the sill. A frigid breeze flowed in through the broken window. The walls of the dark room were lined with paintings, but there was a blank spot next to the high window on University Street. The police ducked the billowing curtains and stepped over the broken glass. A pair of wire cutters lay on the floor. Someone had left a postcard.