Dedicated to my mother, brother Ian and grandson Oliver

All photographs are the work of Richard Brown. The photographic work of Richard Brown can be found at www.arjaybeephotography.co.uk

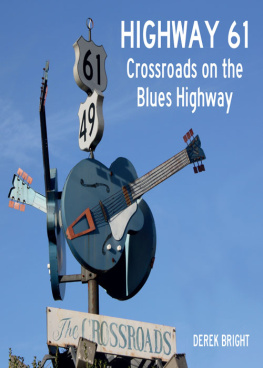

Front cover image: The Crossroads, Clarksdale. (beccasaucier.wordpress.com)

T he author would like to thank the following people for their help, time and encouragement during the research and production of this book.

In particular I would like to acknowledge the support and friendship of Susanna Ernst and Frank Suerth, who gave so much of their time as well as their enthusiasm and passion for the history of Chicago, and without whom much of this book could not have been written.

I would also like to thank those that have shared the journey down Highway 61 with me and have in various ways contributed towards shaping this book. These include Phil Sugden, who undertook the road trip to the Mississippi Delta with me in 2007; my eldest son Jack Bright, who undertook the journey to Chicago and Memphis with me in 2013; and my good friend Richard Brown, photographer, whom I undertook the journey from Chicago to New Orleans with in 2012, upon which this book is based. I am grateful for both his time and patience during the course of our journey, and for his style and expertise, reflected in the numerous photographs that support the text.

I am also indebted to the many kind people we met along the way, who took the time to discuss the themes explored in the book and responded to my enquiries during the course of researching and writing the book. These include: Marc Borms, Luc Borms, Peggy Brown, Brad Cobb, Keith Dixon, David S. Dreyer, Joe Edwards, Bridgette Gray, John Gray, Paul Garon, Bruce Iglauer, Steve LaVere, Bill Lester, Bill Luckett, Carol Marble, Malcolm Mills, James Moss, De Shunn OBray, Steve Pasek, William Patton, Sunshine Sonny Payne, Frank Ratliff, Mickey Rogers, Caneal Rule, Willie Seaberry, Mike Stephenson, Roger Stolle, Don Wilcock and Darrell White.

I am immensely grateful to Johnny Green for kindly contributing the foreword in his own inimitable style, as well as his encouragement and advice during the course of writing the book, which kept me focussed on the journey ahead and stopped me exploring too many by-ways.

Also deserving of my thanks is my wife, Mandy Lowe, who devoted a holiday to undertaking the initial proofread and spent days getting the manuscript into a semblance of order. Thanks must also go to Viv Hotten for his help and constructive criticism on the draft manuscript.

Finally I would like to thank all the blues musicians both alive and dead, who are the subject matter of this book and who have, through their art, immeasurably enhanced my life in so many ways.

W hat could possibly persuade a bright British boy to wind up on Main Street, USA, an exile in Mississippi? Why, an odyssey, of course, to discover not only the birth of the blues but to quench his own burning sense of injustice.

Derek Bright is a driven man on these subjects. So hes made the blindingly obvious move. Hes swung the hired motor down Highway 61 in search of, well, the source of it all. This book continues his theme of inner yearning, a pilgrimage, if you will.

I am entranced. Bright has rewound the tape. This book allows the reader to open the passenger door, climb into the front (preferably bench) seat next to our driver, guide n courier and peer through the windscreen. All the time, Derek tunes the car radio to the very best black music that America has to offer. It is some purposeful road trip.

Yet, you may wonder, what insight does an Englishman have to offer about the blues? The lineage of rediscovery is solid. Ask Keith Richards. English musicians have been flagging up the blues right back to the birth of rock n roll. Lonnie Donegan adapted the genre into homespun skiffle in the 1950s, turning on a generation. The Stones took it all back home, like coals to Newcastle, in the 1960s. Wilko Johnson, in the seventies, referenced Dr Feelgoods music as being from the Thames Delta. During these decades, many great blues men, such as Muddy Waters, had to play in the UK for recognition when they couldnt get a decent gig in their own homeland.

The blues was always there for us. When The Clash first toured the USA in 1979, our support of choice was Bo Diddley. The white punk rockers in the crowd barely knew him. We stood on the side of the stage every night mesmerised like gauche schoolboys and sat at his feet like acolytes on the tour bus. Re-education to his beat was the essential order of the day.

I, like many another youth, learnt in the clubs and the back rooms of pubs from the white acts. I first heard Alexis Korner playin bottleneck guitar, singin gruffly with Victor Brox on pocket cornet in the dingy basement of Les Cousins, off the Charing Cross Road in the mid 1960s. It was a revelation, not a history lesson. John Mayalls Bluesbreakers, featuring Eric Clapton, came to a boozer in my provincial town and blew the place apart with Double Crossin Time. The flood gates opened for Peter Green with Fleetwood Mac and so, so many others. It took an excavation of specialist record shops in London to unearth Robert Johnsons King of the Delta Blues Singers

I was inspired. The tunes directly linked up with my growing radicalism. First time I hit Chicago, I went out on a bar crawl with Joe Strummer. Through good fortune and local guidance, we ended up in some dodgy joint to celebrate ecstatically the birthday of Sunnyland Slim. We criss-crossed that route eastwest, westeast. Bright goes for the jugular, northsouth, back to roots, defiantly peering around the next corner.

But it aint just musical style. Derek comes from a fine tradition of political struggle that makes perfect sense within the blues framework. He never forgets the long battle for emancipation and equality within this supposed sophistication of civilisation. For those of us yet to make this trip into a still-so-relevant psycho-geographical culture, he is our eyes, ears and conscience.

A change is gonna come?

Plenty of folk are still waiting and, in the meantime, still singing their songs of woe n joy.

Johnny Green

Road Manager, The Clash

December 2013

T here are two great American road trips. One is immortalised by Nat King Coles version of the Bobby Troup song Route 66. The highway crosses America from east to west and for many once symbolised the promise of new frontiers and ever-expanding possibilities of the American Dream. For others the route is the epitome of the rock n roll road trip, sassy and chrome-plated.

There is, however, another great highway that cuts across the United States. Designated for much of its length as the Great River Road, Highway 61 runs south for 1,400 miles from Wyoming, Minnesota, to New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico. It doesnt stray far from the banks of the Mississippi River as it drills down into the heart of Americas troubled past. It passes south through towns steeped with the history of modern America; towns inextricably linked with cotton and slavery, civil war and the struggle for civil rights. Alongside these histories one can find the story of Americas most important indigenous musical form, the blues.

Highway 61, also known as the Blues Highway, is followed by those in search of the music created by the black population of the American South. Blues pilgrims are drawn there in search of authenticity in the landscape and its people that is the essence of the blues. As blues harmonica player Sugar Blue said, it is from this crucible the blues was born, screaming to the heavens that I will be free, I will be me. Yet today, the music holds limited interest for Americas black population, but through imitation and incorporation has an immense following worldwide from a largely white male audience of blues enthusiasts.

Next page