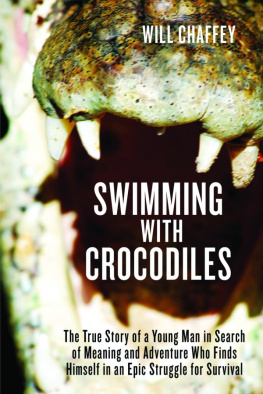

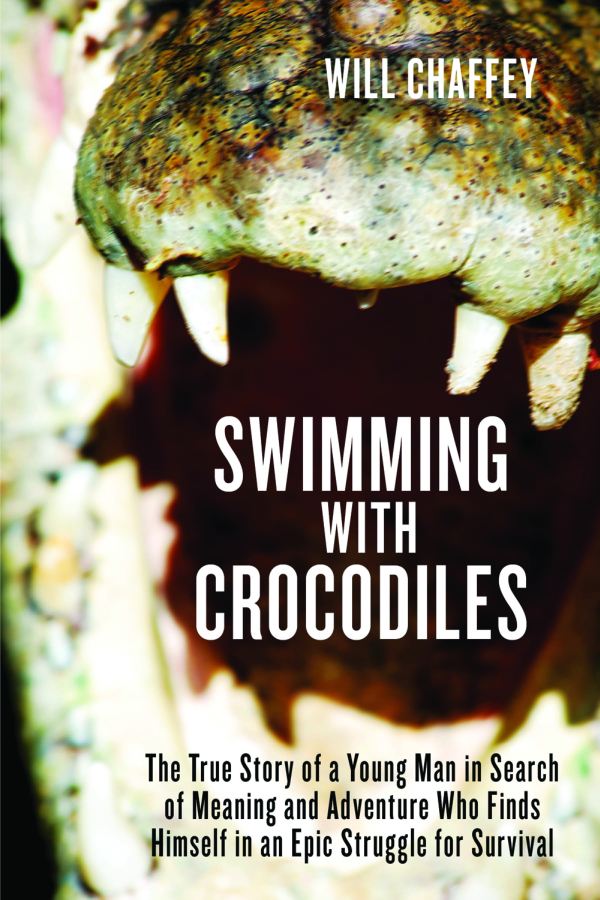

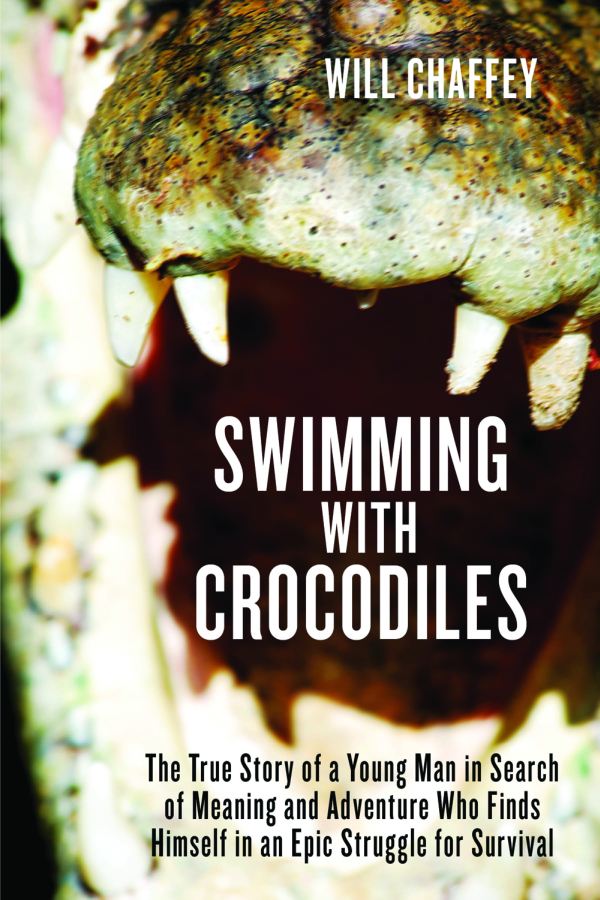

SWIMMING

WITH

CROCODILES

SWIMMING

WITH

CROCODILES

The True Story of a Young Man in Search of

Meaning and Adventure Who Finds Himself

in an Epic Struggle for Survival

WILL CHAFFEY

Arcade Publishing

New York

Copyright 2008, 2011 by Will Chaffey

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Chaffey, Will.

Swimming with crocodiles : the true story of a young man in search of meaning and adventure who finds himself in an epic struggle for survival / Will Chaffey.

p. cm.

Originally published: New York : Arcade Pub., c2008.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-61145-021-7

1. Prince Regent River (W.A.)--Description and travel. 2. Prince Regent River Region (W.A.)--Description and travel. 3. Chaffey, Will--Travel--Australia--Prince Regent River Region (W.A.) 4. Adventure and adventurers--Australia--Prince Regent River Region (W.A.) 5. Wilderness survival--Australia--Prince Regent River Region (W.A.) 6. Crocodiles--Australia--Prince Regent River Region (W.A.) 7. Chaffey, Will--Travel- -Australia--Western Australia. 8. Americans--Travel--Australia--Western Australia. 9. Western Australia--Description and travel. I. Title.

DU380.P75C47 2011

919.414--dc22

[B]

2011002133

Printed in the United States of America

To every person who picked me up beside the road

CONTENTS

SWIMMING

WITH

CROCODILES

CHAPTER 1

THIRST

Let him live under the open sky, and dangerously.

Horace

T he four-wheel-drive track to Port Warrender on the northwest coast of Australia was not frequently traveled. The thin wheel ruts cut past narrow canyons and across palm-studded plateaus of orange sandstone. Termite mounds sat solid as concrete in the middle of the track. As we turned up a hill of yellow grass, a faded sign warned of abundant crocodiles and mosquitoes near the coast. The radio in our jeep picked up nothing but static from one end of the dial to the other.

We had crossed a desert continent to arrive here rattled west from the rain forests hugging the eastern seaboard across the dry flat interior with its roadhouses and isolated towns, through Queensland, the Northern Territory, Western Australia, the Tanami, Gibson, and Great Sandy Deserts, the Durack and Leopold Ranges, and over the rugged basalt, shale, and sandstone plateaus of the Kimberley in a tiny Daihatsu jeep averaging no more than twenty miles per hour.

In the back of the jeep I had a loaf of hard bread, tomatoes, cheese, some spicy sausage, a few cans of sardines, rice, a knapsack with a few spare clothes, a camera, boots, a manual typewriter, and not much else. My traveling partner, Jeff, had brought ten gallons of water and ten gallons of extra fuel in jerry cans. There would be no one to help us here should the jeep break down.

The engine growled in compound low down a final ridge, and the road, such as it was, ended. Jeff and I stepped out into the quiet heat.

North of us, huge inlets of gray mud spread away from the coast. Outcroppings of maroon sandstone rose above the tides, interspersed with green pockets of vegetation. Through all pervaded an intense heat and the vast eternal silence on the edge of outer space.

It was early in the month of May and the beginning of the dry season in the far north. The dry begins with the end of the rains in April or May, and already Crystal Creek was no more than a trickle. In a few more weeks water would evaporate from all but the deepest pools between the rocks. By November the wild dogs and cockatoos would linger by their dwindling waterholes, waiting for rain.

The creek trickled through a fissure in the fractured sandstone a hundred yards away. Jeff stood beside the jeep cutting slices of sausage and cheese onto bread for breakfast.

I walked to the edge of the creek, studying the intersection of blue sky and orange coast under the sun. These rocks may have been the first to emerge from an ocean that covered the entire planet 2,000 million years ago. A white finger of beach jutted into the azure waters of the Timor Sea in the distance.

Having crossed the continent, I wanted to touch the sea.

Pockets of green behind the beach meant mangrove swamps, home of the estuarine or saltwater crocodile, Crocodylus porosus, a creature virtually unchanged since the days of Tyrannosaurus rex and its ilk. In retrospect, I brought with me a great deal of inexperience. The sun shot like a kite into the sky.

Hate to come all this way and not reach the beach.

Not me, Jeff said, chomping on the sandwich under his beard. Watch out for crocs.

My first enduring image of the crocodile was a picture in black and white of a foot and the lower half of a leg rising out of a cardboard box: the remains of a Peace Corps worker attacked near Lake Turkana, Africa, in 1962. He had been twenty-six years old and all that remained of him was a foot and a few pieces of flesh. In the Top End, often all that remains are a few buttons, some fingernails, or a rifle propped against a tree near an innocent-looking billabong, or water hole.

Judging the land from this height, the journey to the beach looked to be no more than two hours walk.

Ill stay here, Jeff said, declining my invitation to walk to the coast, but you go ahead.

Standing beside the jeep, I held my compass at arms length and sighted down the needle to the spit of beach in the distance: a bearing of 300 degrees.

See you in a couple hours, I said and set off, trying to follow the compass heading in a straight line over the broken terrain.

Jeff called after me, Drink plenty of water before you go. At the thin fissure of Crystal Creek I filled my stomach and my canteen with water.

The jeep, a white speck in an immensity of orange stone, disappeared behind me. My eyes moved often from the compass needle to the fractured landscape of boulders and spinifex grass.

Captain Phillip Parker King was the first to systematically chart parts of this thirsty coast back in 1818. He had written of the landscape: The surface of the ground was covered by spinifex, which rendered our walking both difficult and painful; this plant diffuses a strong aromatic odour. The sharp spines poked into my ankles above my boots, but King was right, the fragrance was delightful.

The needle of the compass did not deviate from the symbol N on the face of the dial: magnetic north. I walked carefully, not wanting to tread on a snake, or twist an ankle. Jeff had reminded me how far we were from civilization before I set out: 1,300 miles from Perth, and more than 1,800 miles from Brisbane, Sydney, or Melbourne.

Next page