About the author

Trish Nicholson is a writer and social anthropologist, and a former columnist and feature writer for national media. After an early career in regional government in the UK and Europe, she was for fifteen years a development aid worker in the Asia Pacific, including five years in West Sepik, Papua New Guinea, where she was also Honorary Consul for the British High Commission. For three years she directed the Voluntary Service Overseas (VSO) operations in the Philippines where she later completed a doctoral degree. Further research, on indigenous tourism initiatives in the Philippines, Vietnam and Australia, was partially funded by a grant from the UK Department for International Development. A shifting lifestyle she survived with a sense of humour. Her other works include books of popular science, travel, management, and writing skills. She lives in New Zealand.

www.trishnicholsonswordsinthetreehouse.com

Inside the Crocodile

The Papua New Guinea Journals

Trish Nicholson

Copyright 2015 Trish Nicholson

Photographs copyright 2015 Trish Nicholson

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers.

Matador

9 Priory Business Park

Kibworth Beauchamp

Leicestershire LE8 0RX, UK

Tel: (+44) 116 279 2299

Email:

Web: www.troubador.co.uk/matador

ISBN 978 1784626 150

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Matador is an imprint of Troubador Publishing Ltd

To Clarkson Dikinsep of Ankem village,

whose service to his country was cut tragically short.

And to the many women and men of Papua New Guinea

committed to the welfare of their people.

Note:

All the characters you will meet in this narrative are real people and in a few cases, names have been withheld or changed to preserve their privacy. There are others I knew or worked with who are not mentioned here because to include everyone and every event would make it an impossibly long read.

Contents

List of illustrations

Introduction

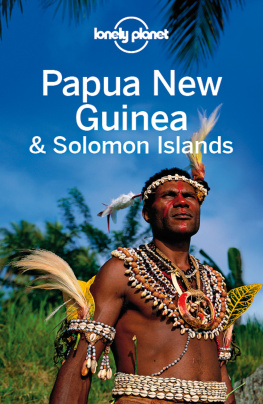

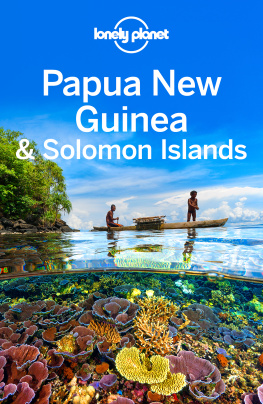

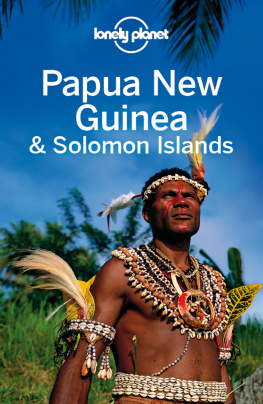

Papua New Guinea is the most diverse nation on earth, rich in resources, natural environment and cultures 800 indigenous languages have been identified and others may exist, spoken by peoples not yet known a complexity that has developed over some 60,000 years of human habitation. The country is an enigma that defies consistent description and there are still white patches of unknown on maps and flight charts that not even Google Earth has penetrated. Like the bird of paradise, just when you think you have it fixed in your camera lens, it flits to another branch in the canopy.

While isolated tribes sustain themselves with their taro gardens and jungle hunting grounds, largely disengaged from the rest of the world, their sons and daughters may be young graduates in the cities, using Facebook and Twitter accounts to participate in a global society. Epitomized as the land of the unexpected, most peoples idea of Papua New Guinea goes little beyond sensationalised travellers tales of cannibalism. A single book cannot explain this extraordinary and exciting country and this is not an attempt to do so. Inside the Crocodile shares my roller-coaster ride of five years living and working in the remote border province of West Sepik Sandaun and travelling to other areas and islands of Papua New Guinea. And it is not only my tale, but that of the Papua New Guineans who became my colleagues and friends. I arrived in Vanimo in 1987, twelve years after independence, to work as a member of the local administration, implementing a development project with World Bank funding.

Of all the countries I might have chosen in which to participate in rural development, this was probably the ultimate test, yet at the time, it seemed the most natural step to take.

I suppose it was inevitable that I would one day work in some far flung corner of the globe. For four generations my forebears had left their roots in the Isle of Man to travel the world. Great-great-grandfather went to Kansas before getting a place in a covered wagon and following the Oregon Trail to San Francisco in the 1800s. His son also went out to Kansas, and was ordained in Topeka. Later generations made extended visits to China, India, Africa and South America. My parents didnt travel, but my handed-down childhood toys included a ball of raw rubber from the Amazon, a single wooden clog from Japan, and a fierce Chinese deity with an arm missing.

While the ancestors had been missionaries, my interests were quite the reverse: I was studying anthropology, I wanted to understand other ways of life and alternative cultures, not convert anyone, but their influence created in me an image of the world as a place to be explored, a curiosity to see what was there, and an attitude that anything was possible.

But interest is not enough. To survive as an alien in unforgiving environments and other cultures one has to be flexible, to accept discomfort and uncertainty. In some cockeyed way, my chaotic childhood in what would nowadays be called a dysfunctional family had prepared me for my future. Constantly moving from one place to another in a state of perpetual insecurity financial and emotional working part-time to pay off household debts while still at school, I was an adult before my teens. But those were the days of education grants in the United Kingdom, not just to stay on at school, but to attend university. Inspired by a teacher to aim beyond my reach, I studied for a joint honours course in anthropology and geography at Durham University.

Armed with a masters degree, I began a career in Scottish regional government, starting as a junior administrator where the skills of filing and tea-making were finely honed. Working up to senior positions and broadening out to management, training, and some freelance consultancy, I was seconded for three years to work on an EEC (now the European Union) exchange programme for young workers. In the cracks of all this work, I became a part-time tutor in the Open Business School and wrote a column for a management magazine and articles for the press. It was all very haphazard; none of it had been planned, things just happened and opportunities arose. But by imperceptible steps, I developed a stronger sense of self with the realisation that I could, and should, create the next phase of my story myself.

In a classic example of Sods Law, the same morning my boss handed me the fax confirming my job in West Sepik, I heard that a publisher had accepted my proposal for a book on staff development. In a final burst of gung-ho everything is possible, and fitting in a night shift to my programme, the book was written in the three months while I waited for a contract from Papua New Guinea. I sent off the manuscript. Whatever happened next would have to follow me to the other side of the world.

The contrasts with Scotland were extreme: from historic cities, snow covered hills and twinkling trout streams, to mountains and ravines smothered in tropical forests two degrees south of the equator, and an average of five people to every square kilometre.