PAPUA NEW GUINEA

Thomas H. Booth

Hunter Publishing, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form without the written permission of the publisher.

For all inquiries, contact Michael Hunter at michael@hunterpublishing.com.

INTRODUCTION

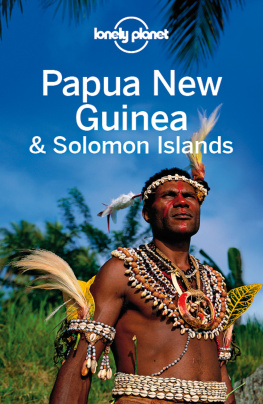

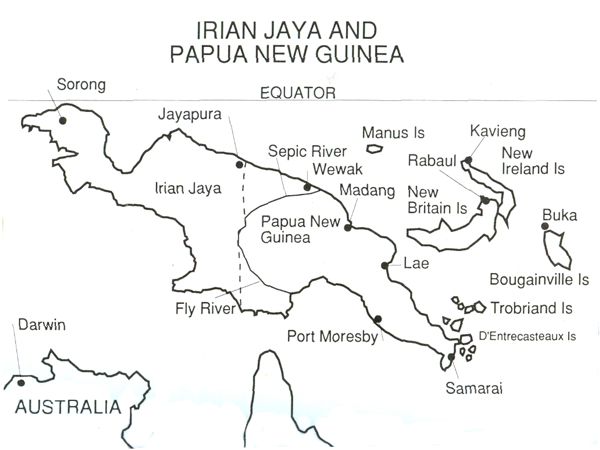

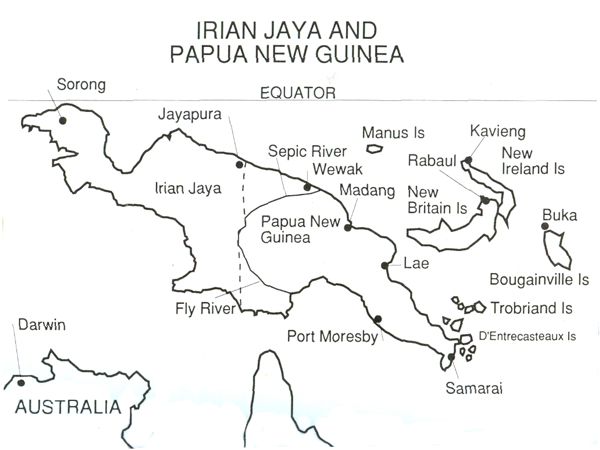

Papua New Guinea, the eastern half of the second largest island in the world, includes a cluster of islands off its northeast coast New Britain, New Ireland, Bougainville, Manus, the Trobriands, and scores of smaller islands.

The other half of the island, the western part-Indonesian Irian Jaya is another story and, other than brief remarks about it, this chapter is confined to Papua New Guinea. However, when you put both halves of the island together, notice how in profile it resembles a huge bird t<;lking off. The head of the bird, a place the Dutch called Vogelskopf (bird's head) is on the Indonesian side. The other end, given no anatomical name by the Australians, is in newly independent Papua New Guinea.

The Dutch left their half of the island after World War II, and things have changed. Vogelskopf is called Manokwari and the town Pacific veterans knew as Hollandia is called Jayapura.

In 1944 when I first saw Hollandia it was suffering from the excesses of war. Seen recently, the same town still suffers, but now it's from Indonesian neglect and a curious military problem on its border.

The eastern half has changed too and as of 1975 Papua New Guinea, calling itself Niugini and its airline Air Niugini, became independent. Fortunately the Australian presence lingers and in a generous way controls the purse-strings. Without Australia Papua New Guinea would probably fall apart. And you're sure to hear commentary on all of this moments after stepping off the plane in Port Moresby, the usual port of entry-particularly if, with an icy South Pacific lager in mind, you go directly across the street and enter the public room of the Gateway Hotel.

There, standing at the bar, you'll almost certainly find a clutch of Aussies, many of them smartly turned out in Aussie gear-shorts, white shirt, and knee-length white stockings. They're sociable people, particularly when they're drinking, and being a newly arrived Yank is apt to get you a slap on the back, a "Good on ya mate;' and another beer.

Then, attended by appropriate ribaldry without which Aussie drinking cannot be sustained, you'll hear a mixed bag of remarks. You may hear that, while matters aren't going flat out for the new government, there's hope, even progress. Perhaps too, you'll hear the other point of view-the Aussie who'll say what bloody cheek the United Nations had to suggest independence for this lot, some of whom a generation ago were stealing each others' pigs and wives and blipping each other on the head.

For a newly arrived American this is a time for listening.

Our point of view is neither required nor recommended. In time someone will sum up all points of view by offering, "But don't get us wrong, mate, this is a good country, and we wish them the very best of luck."

We once fell in with such a group, and in time they asked why we were in Papua New Guinea. I explained that World War II nostalgia drew at me a little, but mostly we wanted to see the Sepik River, the Trobriands, the Highlands, maybe the Kokoda Trail. They approved with noisy enthusiasm, but one of them added, "You're just scratching the surface of this country, mate. There are other rivers to be seen, trails to be walked, mountains climbed, some snow-clad, and with valleys so remote that Stone-Age people live in them. There are jungles with birds of paradise in them, cassowaries, wallabies, little pigmy blokes too. And don't forget the hundreds of islands in the Bismarck Sea off the North Coast that are like little jewels. Remember too that over 700 linguistic groups and cultures share this country."

Someone else broke in, "If it's the Kokoda Trail you're interested in, you'd better come home with us. We're doing a mixed grill, we've got plenty of grog, and Bert here has done the Trail."

We went. It was a fine happy evening, and we awoke the next morning feeling delicate, but enthused about what we'd heard. And our Aussies were right. Two subsequent trips convinced us that New Guinea has everything an adventurer or escapist froz:n the usual could want. But, on balance, Papua New Gumea has far better amenities and transportation facilities than Iri~n Jaya, the western half. The 1987 World Status Map and theIr Official Advisories for International Travelers does advis~ that, "Papua New Guinea has continuing crime problems m both urban and rural areas." They recommend travel with in-country tours instead of independent moving about. ThIS we admIt IS cause for concern, but it has never stopped us from traveling independently. We've done it with caution but happily and safely.

Near Madang, Papua New Guinea

History in Brief

Most of the early people were hunters and gatherers who used stones, bones, and wood for tools and weapons, as some still do. Each group was self contained, about 700 separate and exclusive groups who spoke 700 different dialects, and often knew as little about each other as they knew about the existence of England or Holland.

The first European probably came ashore on the western end of the island, in. what is now Indonesian Irian Jaya. That honor goes to a Portuguese sailor, Jorg de Meneses, who arrived in 1526. Then a few years later the name New Guinea was bestowed on the island by a Spaniard, Ortiz Retes, who thought the natives similar to those on the Guinea coast of Africa. It's now thought that some of these early Europeans introduced the pig and sweet potato to these and other South Pacific Islands.

The cast of foreign visitors continued with Dampier, Bougainville, Schouten and, of course, Cook. They came to chart the coastline and rivers of this very large island, but it wasn't until 1939 that the interior of New Guinea was fully charted. Even now there are areas where no white man has yet stood.

In 1828 the Dutch annexed the western half, leaving the eastern part in a state of colonial confusion. Finally in 1883 England took over the part not claimed by Holland-today's Papua New Guinea. Then there were problems with Germany which, in 1885 after talks with Britain, took over the northeast part of New Guinea.

When World War I broke out in 1914, the Australians made a landing at the German administration center at Kokopo on New Britain and the Germans, who had more pressing matters in Europe, surrendered quickly.

In 1920, the League of Nations gave England the mandate to govern the former German colony. At this point the entire eastern half was under the British-Australian flag and was administered by Australia. The southern part was called Papua, the northern part, New Guinea.

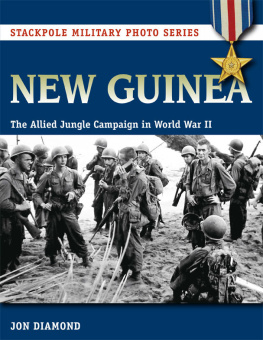

It was in January of 1942 that Japanese troops and their navy landed at Rabaul on New Britain island, capturing 300 civilians and 900 soldiers. Tragically, most of them later lost their lives when their prison ship en route to Japan was torpedoed and sunk.

From Rabaul, Japanese troops moved south to the main island of New Guinea and fanned out, attempting to cross the Owen Stanley mountains and take Port Moresby. They nearly did so, but were halted by Australian-American forces in the Kokoda area. The Japanese then withdrew and were pushed all the way back to Rabaul where they had started. There they dug in and remained until the war's end.