Contents

Guide

Page List

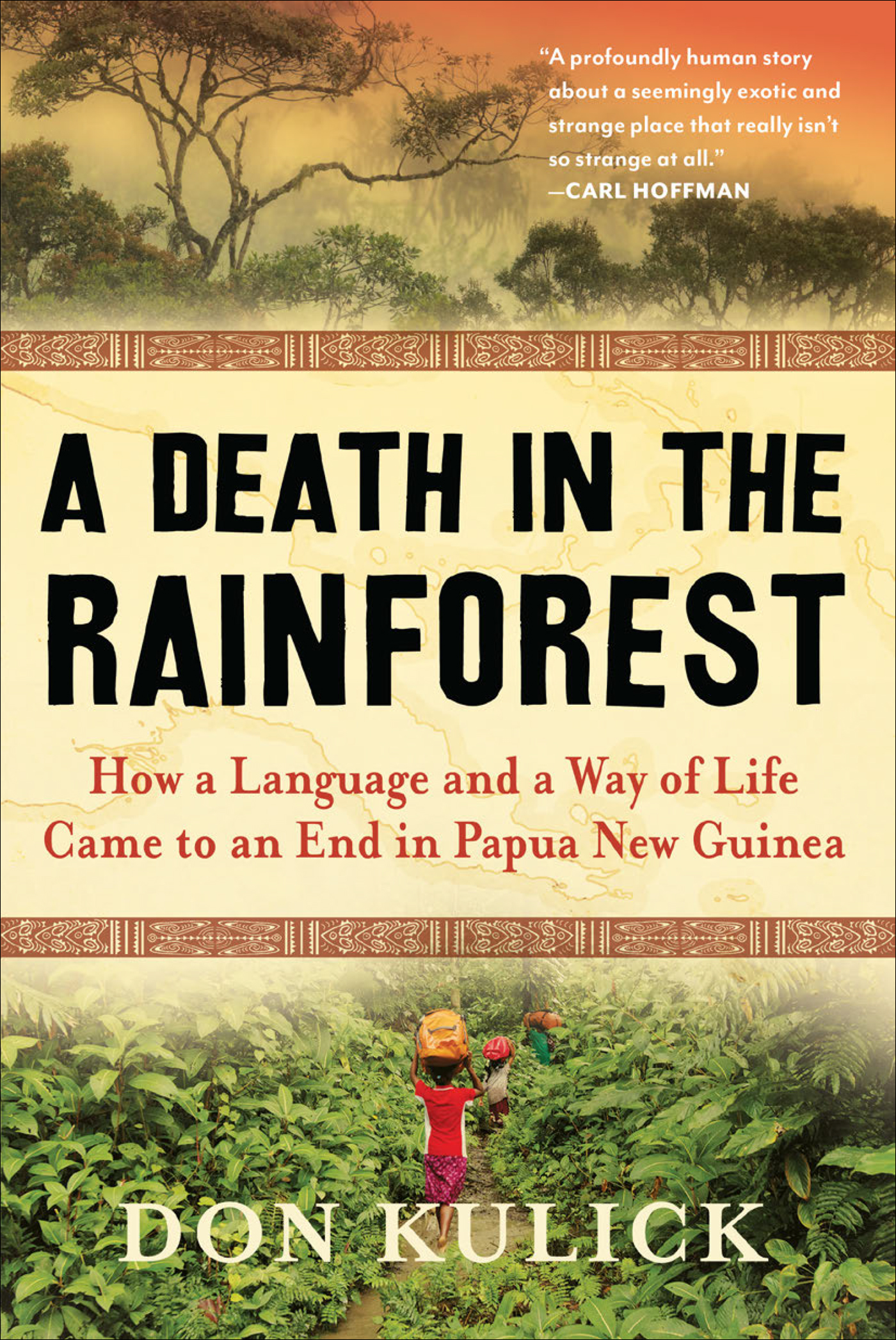

A Death

in the

Rainforest

How a Language and a Way of Life

Came to an End in Papua New Guinea

don kulick

ALGONQUIN BOOKS OF CHAPEL HILL 2019

contents

foreword

F or over thirty years I visited a small village deep inside the rainforest of Papua New Guineaa country that lies not in Africa, as people often believe, but in the Pacific Ocean, just north of Australiato discover how a language dies. The village I came to know during the course of those years is called Gapun. The people who live there all used to speak a unique language that they call Tayap. For all we know, Tayap may be as old as Greek, Chinese, or Latin. But the coming decades will see Tayap die: currently, the language has fewer than fifty active speakers. Soon, all that will be heard of Tayap ever again are the recordings that I have made over the years. They will linger on like ectoplasm, long after the speakers are gone and the language is forgotten.

I first went to Gapun as a graduate student in anthropology in the mid-1980s, and I spent over a year living there then. I wrote a book about what I discovered. It is a good book, a solid study still well worth reading. But it is an academic book, aimed at professional anthropologists and linguists, and university students. Its eye-numbing title, Language Shift and Cultural Reproductionwhich I attribute to an unhappy combination of eager youthful ambition to appear scholarly, and terrible editorial advicesays it all.

This time I am writing from hindsight. A different kind of book: one that tells a story about what has happened in Gapun in the years since I first visited, and about how the Tayap language is fizzling inexorably to its end.

But this book also tells the story of my work in the village, and why that, too, has come to an end.

Both endings are bound up with violence. On the one hand, there is the material and symbolic violence that the coming of white men to Papua New Guinea has wrought on the people there, their cultures, and their languages. On the other hand, there are local acts of violence, perpetrated by villagers themselves and their neighbors, that harm the villagers, and that have harmed or threatened to harm me too. All these forms of violence course like subterranean flows of magma that occasionally gush up and burst through the surface of the stories I tell here. Those stories are about what it is like to live in a difficult-to-get-to village of two hundred people, carved out like a cleft in a swamp in the middle of a tropical rainforest. They are stories about what the people who live in that village eat for breakfast and how they sleep. They are stories about how villagers discipline their children, how they joke with one another, and how they swear at one another. They are stories about how villagers romance one another, how they worship, how they argue, how they dieand also how they made sense of a white anthropologist who appeared one day out of nowhere, saying he was interested in their language and asking their leave to stick around for a while.

A while that ended up extending over three decades.

C an one speak for another? Since I wrote my first book about Gapun twenty-five years ago, a sometimes rancorous discussion has erupted both inside the academy and outside it, about the legitimacy of writing about a group of people to whom one as a researcher does not, oneself, belong. Long gone are the magisterial days of departed anthropologists like Margaret Mead, whose attitude about the people she worked with was neatly summed up in an article she published in 1939 in the professional journal American Anthropologist. Mead wrote in response to one of her colleagues claims that for anthropological work to be believable, anthropologists needed to learn the languages spoken by the people among whom they did fieldwork.

Margaret Mead thought that earnest counsel like that was nonsense. She waved it away like an irritating housefly. All the fuss about learning native languages was intimidating to anthropology students and just plain wrongheaded. It wasnt necessary.

To do their job, Mead insisted, anthropologists dont need to know a language. They just need to use a language. And to use a language requires only three things.

First of all, you need to be able to ask questions in order to get an answer with the smallest amount of dickering. (What you were supposed to make of those answers if you didnt speak the language in which they were delivered was not something that Mead seemingly bothered herself about.)

The second thing Mead thought that an anthropologist needed to use a language for is to establish rapport (Especially in the houses of strangers, where one wishes the maximum non-interference with ones note taking and photography).

The final thing you need to use a language to dothis is my favoriteis to give instructions. Invoking an era when natives knew their place and didnt dare mess with bossy anthropologists, Mead offered this crisp advice: If the ethnologist cannot give quick and accurate instructions to his native servants, informants and assistants, cannot tell them to find the short lens for the Leica, its position accurately described, to put the tripod down-sun from the place where the ceremony is to take place, to get a fresh razor blade and the potassium permanganate crystals and bring them quickly in case of snake bite [wouldnt you love to know how she barked that in Samoan?], to boil and filter the water which is to be used for mixing a developer,he will waste an enormous amount of time and energy doing mechanical tasks which he could have delegated if his tongue had been just a little bit better schooled.

Since Meads time (she died in 1978), and partly in response to the imperious hubris with which she and other anthropologists of her era presented the people they wrote about, scholarsas well as some of the women and men who provided anthropologists with the material about which they wrotehave raised the thorny issue of speaking for others. Can one do it? Should one?

I am a white American/European middle-class male professor writing about largely moneyless (which is not the same as poor) black villagers who live in a backwater swamp in a faraway Oceanic country. The immense differences between me and the people whose lives I describe here mean that all the triggers are present from the outset. The ground is strewn with easily visible mines.

Like most card-carrying anthropologists, however, I remain committed to the spirit of Margaret Meads conviction that we not only can, but we shouldindeed, we have a responsibility toengage with and represent people who are very unlike ourselves. If anthropology as a way of approaching the world has a single message, it is that we learn from difference. Difference enriches. It disquiets, it expands, it amplifies, it transforms. Engaging with difference respectfully always necessarily entails risks: political and epistemological risks (you might get it all wrong), representational risks (how do you describe peopleincluding their idiosyncrasies or shortcomingsin a dignified manner without being patronizing, hagiographic, or sentimental?), and personal risks (encounters with difference are frequently transformative in unpredictable and sometimes even undesired ways. Plus, you incur responsibilities and long-term, often unrequitable debts).