Douglas W. Jacobson

THE KATYN ORDER

Courage is the first of human qualities because it is the quality that guarantees all others.

Winston Churchill

I have heard it said that the most difficult book for an author to write is the second one. I have, indeed, found that to be true. The story that finally came to fruition as The Katyn Order took many twists and turns along the way, as well as several false starts. As with my first book, this effort could not have succeeded were it not for the help of many people.

At the top of that list is my editor, Jackie Swift, of McBooks Press. Were it not for her seemingly inexhaustible patience, sound advice, and flat-out awesome skill as an editor, this book never would have happened. Jackie knew what story I wanted to tell and was determined not to let me off the hook until I told it.

Many thanks to Swalomir Debski, who again served as a valuable reference, particularly on the background of Katyn and Soviet-Polish relations during this time period.

My friends and fellow authors at Redbird Writers Studio in Milwaukee continued to provide their usual candor and constructive critique, which was extremely helpful in developing the relationship between Adam and Natalia.

My friend Krystyna Rytel, of Elm Grove, lived through the occupation of Poland and the Warsaw Rising as a child. In sharing her experiences, Krystyna helped provide an emotional understanding of those unimaginable times.

I also want to thank the real Tim Meinerz for his generous donation to the Multiple Sclerosis Society Scholarship Fund. It was a privilege to name a character in this story after him.

And, as always, I am eternally grateful for the patience and encouragement of my wife, Janie; Kevin and Mary; Kerri and Filip; and our seven grandchildren who, once again, put up with my absence while I burrowed away for countless hours.

KATYN FORESTNEAR SMOLENSK, RUSSIAAPRIL, 1940

THE POLISH OFFICERS knew they were in trouble when the train stopped.

At first they were quiet. After a time some began to pray, some cursed. But most stood in silence in the dark interior of the boxcar, waiting. They were officers, their pride untarnished in defeat. And they waited.

From outside, heavy boots marched on the gravel rail siding, dogs barked and soldiers shouted orders in Russian.

The doors of the boxcar were pulled back, grinding and scraping on rusty tracks. The officers filed across the rail yard as instructions in Polish blared over loudspeakers.

Autobuses arrived, their windows blackened, their rear doors open wide like the jaws of serpents. Inside the buses were cages: one Polish officer per cage, thirty officers per bus. The doors slammed shut.

Darkness.

A rutted road led deeper into the forest, out of earshot, away from prying eyes away from everything.

The officers hands were bound. Names were recorded in books that would never see the light of day.

A narrow path disappeared into the trees, still deeper in the forest.

It was a crisp, clear April morning. Tree sparrows flitted about, crocuses were budding, the forest awakening. The ferns were wet with morning dew, the air heavy with the dank odor of mossand the stench of death.

A Russian major stood near an open pit, a gaping hole, an obscene scar on the pristine landscape.

The major barked a command, and Russian soldiers shoved a Polish officer to the edge of the pit. The Pole stared into the carnage, then looked at the major. Their eyes met for an instant. The major turned away.

A Russian soldier put a pistol to the back of the Polish officers head. It was easier if he didnt have to look them in the eye.

A gunshot echoed through the silent forest.

The sparrows flew away.

The major made a check in his log. There would be more than twenty thousand checks before it was finished.

According to the Order.

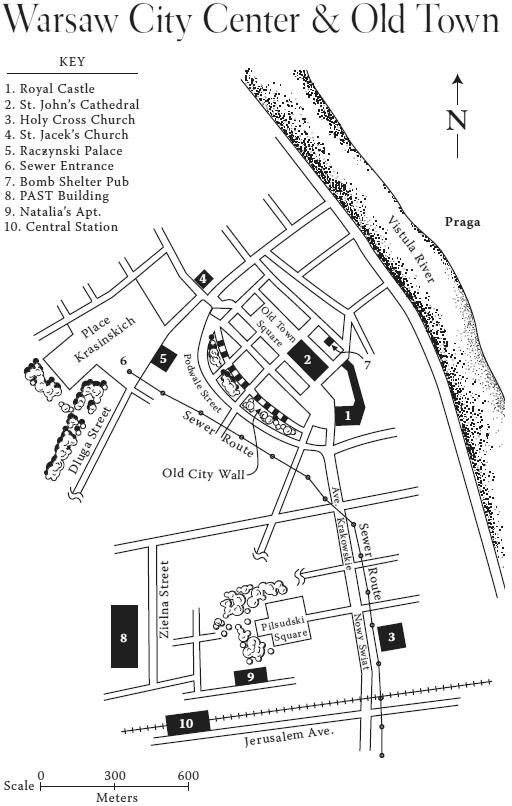

5 AUGUST 1944

THE ASSASSIN STOOD IN THE SHADOWS of an alcove and watched the activity on the other side of the street. The lamps along Stawki Street, just west of Warsaws City Center, had been shot out during the first days of the Rising, but the night sky was illuminated with brilliant, yellowish-white flashes. German artillery units were pounding the Wola District two kilometers to the west, and an acrid, smoky haze hung in the air. The ground trembled beneath his feet with each jarring concussion.

But he waited.

And watched.

A few minutes earlier, two canvas-covered trucks had pulled up in front of the deserted three-story warehouse, and several prisoners wearing black-and-white concentration camp uniforms had jumped out and begun unloading wooden crates. Two German SS troopers with automatic rifles watched over them, glancing at the western sky whenever a particularly loud burst of artillery echoed through the streets, shattering the last unbroken windows. The SS troopers appeared nervous, though this neighborhood was still under German control.

The assassin checked his watch. It was almost time. He brushed the dust and specks of ash off the front of the uniform hed taken from the dead Waffen-SS trooper the night before. He had made sure it was a clean shot to the head so as not to soil the jacket with blood. He wanted to look his best for SS-Sturmbannfuhrer Karl Brandt.

At exactly 2200 hours, a flash of headlights swept through the gloom as a long, black auto wheeled around the corner and screeched to a stop behind the trucks. The driver jumped out and opened the rear door of the powerful German-built Horch. The assassin watched as SS-Sturmbannfuhrer Brandt squeezed out of the backseat like an over-ripe melon and tugged on the bottom of his uniform tunic in a futile effort to cover his sagging beltline. The obese officer barked a command to the SS troopers and plodded toward the warehouse.

The assassin stepped out of the alcove and marched across the boulevard, his right hand resting lightly on the holster strapped to his waist. As he approached the automobile, he shouted loudly enough to be heard over the bursts of shelling, Guten Abend, Sturmbannfhrer! With his right forefinger, he flipped open the strap of the holster.

SS-Sturmbannfuhrer Brandt stopped and turned toward the street, a bewildered look in his eyes. Ja, was ist

The assassin drew the Walther P-38 from the holster and in one smooth motion fired a single shot into Brandts forehead, then a second into the chest of the driver. He stepped over Brandts body and fired two quick shots at the SS troopers, who stood staring at him in frozen astonishment. One of them went down instantly. The other required another round.

The striped-uniformed prisoners dropped the crates and stood ramrod stiff, arms in the air, their faces white with fear. An instant later, a group of men wearing red-and-white armbands bolted from the shadows of a building across the street. Brandishing an assortment of weapons, they charged past the stunned prisoners and barged into the warehouse.

From inside, shouts in Polish and German

Gunshots

Then it was quiet.

The assassin calmly approached the quivering prisoners and holstered his gun. From his pocket he withdrew a red-and-white armband, emblazoned with the Polish eagle, and slipped it on. Were AK, he said. Armia Krajowa, the Home Army. Get inside.