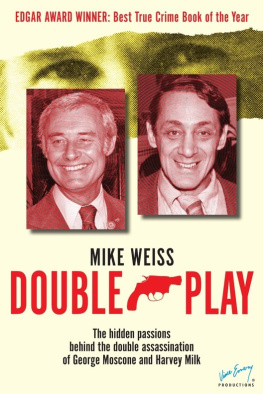

M IKE WEISS covered the trial of Dan White and its aftermath the White Night riots for Time Magazine , Rolling Stone , and the Los Angeles Times .

In addition to his Edgar Award-winning true crime thriller Double Play (1984 and 2010 editions), Mr. Weiss is the author of the nonfiction books Living Together: A Year in the Life of a City Commune (1974) and A Very Good Year: The Journey of a California Wine from Vine to Table (2005). He also wrote the acclaimed Ben Henry mystery novels No Go on Jackson Street , All Points Bulletin , and A Dry and Thirsty Ground. His work has appeared in Esquire, Mother Jones , the Guardian, the San Francisco Chronicle , the Village Voice, and other publications.

Mr. Weiss was raised in New York City, educated at Knox College and Johns Hopkins University, and worked for many years as a reporter in San Francisco. He lives in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Authors Note

I T WAS WHILE COVERING DAN WHITES murder trial (for Rolling Stone and Time magazines, as well as writing opinion pieces for the Los Angeles Times) that I began to consider writing a book about the incident at San Franciscos City Hall on November 27, 1978. The trial became my obsession, a sharply-etched recurring nightmare. So much that could and should have been said was not. The courtroom, for all that it was starkly lit, was a dark and awful place. Political and psychological passions were suppressed, for reasons that were themselves political and psychological. 1 understood that passion had no place at a trial, which after all is a kind of societal prophylactic protecting us from vengeance. And yet the absence of passion, when it is so deeply felt in the blood of the acts, creates a pornographic atmosphere. The less we know, the more circumscribed our emotions, the more lurid things seem.

At first my guiding feeling was that Dan White was a reactionary punk, a man whose own much-invoked moral code should have prohibited him from hiding behind psychiatric doubletalk and his wifes heartbreaking tears. One moment it was easy to despise Whites lawyer, Doug Schmidt, for being so cunning in such an unworthy cause, but the next it was impossible not to admire his cleverness on behalf of his client. I wanted theprosecutor to prove the case for first-degree murder and was dismayed by the ponderous ineptitude of Thomas Norman and contemptuous of the selfish, politically-motivated trial strategy endorsed by his boss, District Attorney Joseph Freitas. In the final analysis, Dan Whites light sentence was their failure. But as the trial proceeded, my anger, which had been severe enough to make me physically ill, gave way to a grudging acknowledgment of what a trial is and what it isnt. What I slowly came to see was that both lawyers cases were partially valid and yet neither was entire of itself. Whatever happened on November 27, 1978, was more subtle and more complex than would be revealed by the trial. Lawyers are paid to employ only as much of the truth as benefits their clients.

The trial ended. The law triumphed over justice. I felt cheated, my curiosity wasnt satisfied. The citys leaders, and most of the rest of us, consigned the events at City Hall to a limbo of partially absorbed forgetfulness. Life went on. When what had happened was mentioned, it was usually with a murderous bitterness (in 1982 Supervisor Carol Ruth Silver told me that if she ever bumped into Dan White on a street corner, I would kill him), or else with a mocking glee by people who had hated Moscone and Milk as viscerally as White had (Gina Moscones better off with him dead, said an anonymous caller to a radio talk show). But most San Franciscans kept their own counsel. Mention Whites name and a shamed, angry silence descended. No other single event of our time more acutely reflected the terrible divisions in our city, those divisions which the Chamber of Commerce and most politicians papered over with civic-minded Babbittries.

White was sentenced to seven years, eight months in Soledad Prison for his two manslaughter convictions and related gun charges. With time off for good behavior (he has been a model prisoner and has received no psychiatric or psychological treatment), plus the time he served in city jail before and during his trial, he was due to be released on January 6, 1984. It is his hope to emigrate to Ireland. When he regained his freedom he was thirty-seven years old.

As the time for his release drew nearer there were several attempts to keep Dan White in prison. The Governor was asked to revoke Whites parole; the U.S. Department of Justice was asked to prosecute him for violating the civil rights of Milk and Moscone. The newspapers speculated that he would be killed if he returned to San Francisco. There was a steady drumbeat of stories. The fury provoked by his most perverse acts and his lenient sentence lingered. It still lies just below the surface. Still and all, most people here in San Francisco chose to turn away from the memory. Icould not. Understanding is no panacea, but it can be a bridge over which we can move forward. This book is my bridge.

I didnt begin to work on Double Play at once; other things kept me from it. As time went on, occasional stories in the newspapers brought back the pain of loss. George Moscones widow Gina was awarded a pension and the story itemized the benefits that came to her and her children. The total was more than $700,000. It was a grim irony that because her husband had been slain she was financially secure for the first time in her life. Another story reported that a child had been born to Mary Ann White after a conjugal visit with her husband at Soledad. The newborn child was afflicted with Downs syndrome.

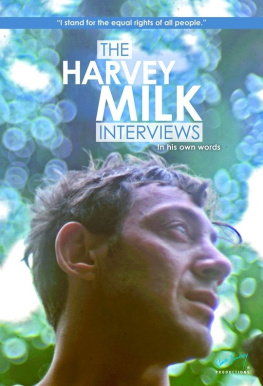

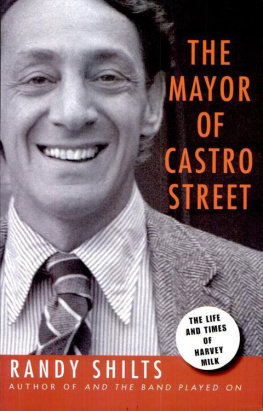

I finally decided to write this book after being interviewed by Randy Shilts, who was researching his biography of Harvey Milk. As I answered his questions a beehive of thoughts and memories came swarming back and could no longer be avoided. As luck would have it, just a few days later I was called by Dianna Waggoner, who at that time was an editor for Addison-Wesley Publishing Company. She asked if I wanted to do a book for them. I did.

In the course of conducting more than two hundred interviews, and while examining tens of thousands of pages of public and private documents (trial and hearing transcripts, reports and testimony from six psychiatrists, minutes of Board of Supervisors meetings, newspaper coverage, personal diaries, police reports, and the likemany of which were never available to any other investigator), I began to piece together the facts about the two dead men and their killer. White turned down my request for an interview, as he did all other interview requests. Once the trial was over his wife also stopped talking with me. I was left with very little choice in my method. Because the principal characters in this drama were not available to be interviewed, I had to work more like an historian than a reporter, interpreting as well as recording. I have taken every care to recreate events as faithfully and accurately as possible.

Gathering, checking, confirming, organizing and filing facts and recollections was a necessary first step. But making them add up to a story which revealed the truth about these three men and their city was, and had to be, a labor of informed inquiry.