EROTIC CITY

EROTIC CITY

Sexual Revolutions and the Making of Modern San Francisco

JOSH SIDES

Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further

Oxford Universitys objective of excellence

in research, scholarship, and education.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Copyright 2009 by Oxford University Press, Inc.

Published by Oxford University Press, Inc.

198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016

www.oup.com

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sides, Josh, 1972

Erotic city: sexual revolutions and the making of modern

San Francisco / Josh Sides.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-19-537781-1

1. Sex customsCaliforniaSan FranciscoHistory. I. Title.

HQ18.U5S543 2009

306.77097946109045dc22 2009002743

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

For Rebecca

EROTIC CITY

INTRODUCTION: FRED METHNERS STREET

Beginning in the mid-1960s, the spectacle of sexuality appeared on the streets and in the public places of large cities throughout the United States in ways that had been unimaginable at any other moment in the nations history. The increasingly public nature of sexualitya critical dimension of a larger moment in history that we call the sexual revolutionwas rapturous for sexual revolutionaries. It was empowering for gays, lesbians, and bisexuals who could finally express their affection, though never truly free from fear; it was liberating for unmarried women and men who shacked up before marriage, often to the wagging consternation of their older neighbors. It was ecstatic for the young men who crowded aroundand even occasionally paid to enterthe thousands of strip clubs, sex shops, and massage parlors that dotted the urban landscape like a neon constellation. And it was profitable for the small armies of female and male prostitutes who swarmed from the hinterlands to the nations big cities, recognizing that sexual freedom need not be free. Sharing their profits in the highly sexualized metropolis were legions of pornographers, whose wares, once relegated to the back rooms of only the seediest skid row stores before the sexual revolution, were now displayed prominently in storefront windows throughout the cities, and even in the suburbs. For so many, the sexual revolution was an extended engagement with, and celebration of, the human libido.

But Fred Methner was definitely not celebrating. Since assuming the role of Secretary and official spokesman for the East & West of

Since the early sixties, Methner had made regular excursions to meetings of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors and the City Planning Department to complain about small assaults to the character of Noe Valley. In fact, this parochial districtwhich had emerged in the late nineteenth century as a streetcar suburb tied to the downtown, waterfront, and South of Market areaswas largely unscathed by the sweeping economic and social transformations taking place in San Francisco during the 1960s and 1970s. But even small infractions warranted Methners attention. He had lobbied the board to criminalize the posting of advertisements on telephone poles and, failing in that, went around tearing them down himself. He fought for, and won, a zoning ordinance forbidding the opening of any new liquor stores in Noe Valley, as well as a very sensible ordinance outlawing dog waste on sidewalks. In 1970, Methner rallied over five hundred Noe Valley residents in a protest against the San Francisco Department of Public Health (SFDPH), which sought to build a mental health clinic on Twenty-fourth Street near Church Street. He derided what he personally considered would be a glorified drug center catering to the weakness and lassitude of hippie culture. Hippies, Methner insisted, were not only drug addicts but also the ones who are causing the VD epidemic. He and his supporters ultimately convinced the SFDPH to abandon the plan.

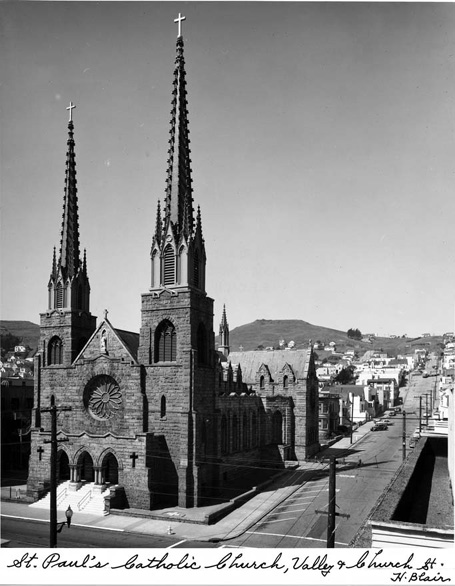

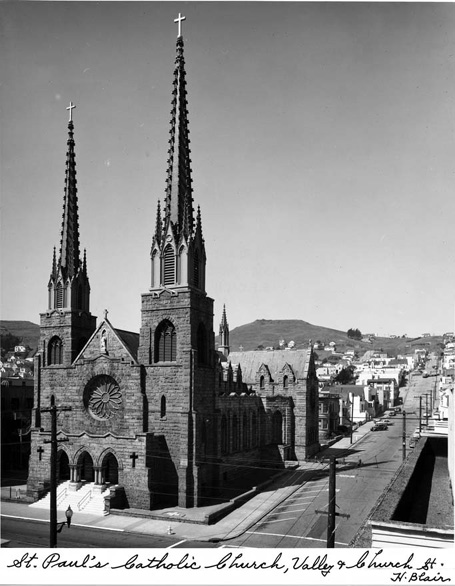

FIGURE 1.1. St. Pauls Catholic Church, the spiritual and cultural heart of Fred Methners Noe Valley neighborhood. Courtesy: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.

By the late seventies, Methner was a seasoned veteran of neighborhood defense, but few of his battles prepared him for what he saw one morning across the street from the St. Philips school at Diamond and Twenty-fourth

As he had so many times before, Methner won the battle: an extremely ambitious city supervisor named Dianne Feinstein had been working for almost a decade to reverse the visible cues of the sexual revolution in San Francisco, and she finally secured passage of an ordinance restricting adult entertainment businesses in 1978, shortly after Methners heated protest at the Planning Department. But he was losing the war. Feinstein had conceded as much when she grudgingly admitted to a New York Times reporter in 1971 that San Francisco had become a kind of smut capital of the United States.

Methner and his neighbors were part of what was increasingly being calledoften disparaginglythe old San Francisco. But there was absolutely no love lost: Methner and his embattled peers wanted nothing to do with the new San Francisco, a city whose skyline was being transformed by massive new skyscrapers, whose factories were closing, and whose neighborhoods were flooded with men and women who worked not with their hands but with their heads, others who seemed to work not at all, and still others who brazenly flaunted their unwholesome sexuality. Indeed, Methner and his neighbors likely saw themselves as victims of two simultaneous revolutionsone economic and one social. Once a city of roughnecks, craftsmen, and financiers, San Francisco was becoming a white collar corporate center par excellence. Manhattanizationas critics called itbrought thirty-one new skyscrapers to the downtown in the late 1960s, and a construction boom in downtown hotels and convention centers followed quickly in the 1970s.

Although there were certainly exceptions to this rule, Caen had it about right. The results of a 1974 survey conducted by San Francisco Focus magazine, for example, revealed that 74% of respondents under thirty years of age felt that adults who wished to see pornographic films should be allowed to do so, while only 25% of respondents over sixty believed this. Similarly, 77% of respondents under thirty disagreed that homosexuality should be a crime, but only 29% of those over sixty did.

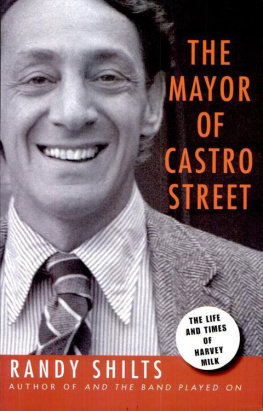

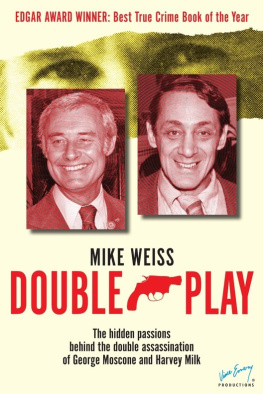

Fred Methners crusade is an easy one to overlook when considering the cultural history of a city that became famous in the 1960s and 1970s for producing silicone-enhanced topless dancer Carol Doda, fratricidal pornography impresarios Jim and Artie Mitchell, and supervisor Harvey Milk, one of the nations first openly gay politicians. Yet an understanding of the reactions of Methner and those like him illuminates essential dimensions of the history of both the sexual revolution and the postwar American metropolis that have been invisible in most accounts. The sexual revolution is remembered as an era in which the individual pursuit of higher consciousness and physical ecstasy became part of the zeitgeist, and a time in which millions of personal sexual revelations, as well as countless experiments in erotic communalism, permanently shattered sexual taboos in the United States. Famed participant-observer Todd Gitlin remembers that the sex was ethereal and that the point of the sixties cultural revolution was to open up a new space, an

Next page