Publication of this book was made possible in part by

THE DONALD R. ELLEGOOD INTERNATIONAL PUBLICATIONS ENDOWMENT

and a grant from the

CHIANG CHING-KUO FOUNDATION FOR INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARLY EXCHANGE

2015 by the University of Washington Press

Printed and bound in the United States of America

Composed in Warnock, a typeface designed by Robert Slimbach

18 17 16 15 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

www.washington.edu/uwpress

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Clark, Anthony E.

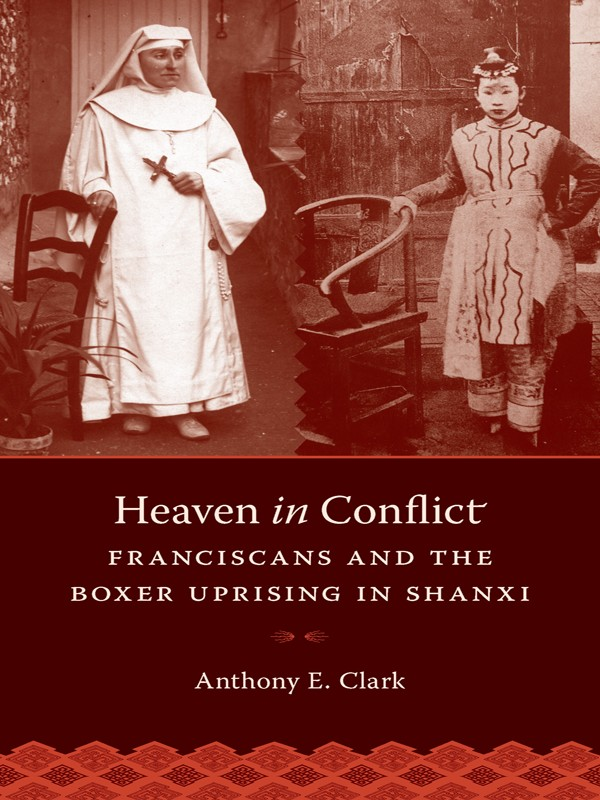

Heaven in conflict : Franciscans and the Boxer uprising in Shanxi / Anthony E. Clark. 1st edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-295-99400-0 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. FranciscansChinaHistory19th century. 2. FranciscansChinaHistory20th century. 3. ChinaHistoryBoxer Rebellion, 18991901. I. Title.

BX3646.C5C53 2014

951'.035dc23

2014007525

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

ISBN 978-0-295-80540-5 (electronic)

Acknowledgments

THIS book began to form in my mind while I worked in my Beijing apartment during the Olympics in 2008; I read through materials related to the Shanxi Sino-missionary conflicts of 1900 while China spun around me, and while the city skies were lit with fireworks during the closing ceremonies. Looking back, this was an appropriately dramatic backdrop to the narratives I was reading for the first time, of warm friendships, growing tensions, tragic violence, and hopeful reconstruction. As I continued to conduct research in Beijing, Taiyuan, Rome, and Paris, and in university archives in my native United States, the principal themes of religious and cultural resistance, defiance, and accommodation persisted as I confronted the history of Franciscan encounters with Boxers during the Boxer Uprising. In his famous classic work on military strategy, Sunzi (ca. 554496 BCE) wrote that supreme excellence consists in breaking the enemys resistance without fighting. As I sought to bring light to these haunting reflections, I received the unselfish and generous assistance of several people, institutions, and granting agencies. While I researched and wrote about tension and conflict between peoples, I encountered only warmth and hospitality, and to the following friends I render my warmest gratitude.

Generous grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities/American Council for Learned Societies and the Chiang Ching-Kuo Foundation allowed me to remain in China during the 20122013 academic year while on a leave of absence from my busy teaching schedule at Whitworth University; without the kind support of these agencies this project would likely still be on the back burner. Previous manifestations of this research were facilitated by the substantial support of the William J. Fulbright Foundation as I completed a year of work as a Fulbright scholar, and by the National Security Education Program, the Congregation of the Mission Vincentian Studies Institute (DePaul University), and the Weyerhaeuser Foundation Research Grant provided by my home institution. I thank my colleagues at Whitworth University, especially my friends in the Department of History, whose support and encouragement remind me often how fortunate I am to work and walk beneath the tall pines that shelter our campus.

The American poet and essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson (18031882) once wrote, The mass of men worry themselves into nameless graves while here and there a great unselfish soul forgets himself into immortality. There are more unselfish souls who made this work possible than I can acknowledge here. Leland and Carol Roth are among them, Lee for scanning rare documents and Carol for helping make sense of them; especially Carols fierce editorial pen has solicited from me many a grateful sigh. My understanding and navigation of the complex ecclesial and scholarly landscape of Taiyuan and surrounding locations related to this study were facilitated by Liu Anrong and my dear friends Anthony and Veronica Fok, who accompanied me on many trips here and there in Shanxi and Hebei. Michael Kellys expertise was most welcome in helping me understand the labyrinthine Latin documents from the Vatican Archives. Dale Soden was a much-needed sounding board for ideas as I worked through some perplexing assessments, and his assistance with a scholarly grant allowed me to make important visits to archives in both Taipei and Rome. James Fox, Cassie Schmitt, Tanya Parlet, and Bruce Tabb at the University of Oregon Special Collections tolerantly helped me locate and consult the exceptional China missions collection in their archive. Martha Smalley at the Yale Divinity School Library generously provided me with access to critical materials held at Yale. Wang Renfang and his assistants at the Xujiahui (Zikawei) library, the former Jesuit library in Shanghai, especially Shen Shuyin and Ming Yuqing, were most accommodating as I perused and photographed the vast collection of materials there related to Roman Catholic missionary cases in late-imperial China. Wu Yinghui and Sun Miqi at Minzu University of China very generously helped manage the complicated process of securing a visa and lodging in China for me to use while writing this book as a visiting scholar. In significant ways, friendship and intellectual repartee with Stephen Durrant, Lionel Jensen, Eric Cunningham, Matthew Wells, and Wu Xiaoxin have influenced the narrative of this work. Shan Yanrong and Jean-Paul Wiest at the Anton Chinese Studies Library at the Beijing Center selflessly provided helpful advice on where to locate important documents. The works of and my correspondence with Henrietta Harrison have helped direct this work in unexpected directions. The assistance of Tulia Barbanti was gratefully received, for without her decryption of the attractive but impenetrable French cursive of the Franciscan Missionaries of Mary (FMM) correspondence in Shanxi, my understanding of the letters would have been nearly impossible. Georges Hauptmann has provided me with enlightening materials related to the architectural work of the Franciscan friar Barnabas Meistermann, OFM, who designed the convent of Dongergou in Shanxi. Thomas Reilly, Christopher Johnson, and Susan Gorin-Johnson all saved me from embarrassing errors and recommended valuable new directions of inquiry as they read through drafts of this book. Riccardo Pedrini, at the Archivio Storico della Provincia di Cristo Re dei Frati Minori dellEmilia Romagna, very generously searched for and sent to my office rare photographs of the Franciscans discussed in this book.

I thank my editor, Lorri Hagman, the anonymous reviewers, Bonita Hurd, and the patient and gifted staff at University of Washington Press, including Jacqueline Volin, Rachael Levay, Beth Fuget, Kathleen Jones, and Tim Zimmermann, who deserve much more thanks than I can render here. The process of bringing this work from desk to bookshelf was made more pleasant, and was much improved, by their invaluable contributions.

After writing a Catholic archive seeking permission to access their voluminous collection of letters, records, and images, I received an unexpected reply: You are welcome, Professor, the letter began, but please, please remember our goal was always to honor God and serve people in need. As I later worked through their materials I understood the impulse behind the archivists reply; several researchers before me had written what the archivist believed were unfairly biased, scathing accounts that perhaps misrepresented what the missionaries had written and done in China during the late-imperial era. I hope that my representation of the sources I consulted for this project fairly and accurately depict the foreign missionaries I studied, and that what I have written represents an objective engagement with the many heartrending personal accounts, both Western and Chinese.