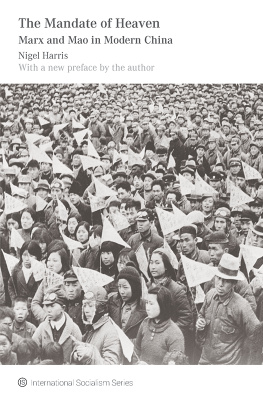

Ban Gus History of Early China

Anthony E. Clark

Abridged Student Edition

Amherst, New York

Copyright 2008 Anthony E. Clark

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior permission of the publisher.

Requests for permission should be directed to: permissions@cambriapress.com, or mailed to: Cambria Press 20 Northpointe Parkway, Suite 188 Amherst, NY 14228

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Clark, Anthony E.

Ban Gus history of early China / by Anthony E. Clark.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-60497-561-1 (alk. paper)

1. Ban, Gu, 3292. Han shu.

2. ChinaHistoryHan dynasty, 202 B.C.220 A.D.

3. HistoriographyChina.I. Title.

DS748.P38 C53 2008

931.04dc22

2008037847

For Amanda

At times our own light goes out and is rekindled by a spark from another person. Each of us has cause to think with deep gratitude of those who have lighted the flame within us.

Albert Schweitzer

Acknowledgments

First, I would like to thank Toni Tan and her colleagues at Cambria Press for their kind encouragement and support. I also thank my anonymous readers who rendered invaluable advice and corrections; they shall find their suggestions reflected throughout this work. This book has benefited from the comments of several peoplecolleagues, friends, and family. Early drafts have had the advantage of being read by Maram Epstein, who helped me to find details, often curiously entertaining, in passages that I otherwise would have overlooked; Ina Asim, who has helped an overall literary study become more historical; Michael Fishlen, who has demonstrated to me that below the text is a hidden narrative where the author is more personally present; Charles Sanft, who pointed out several embarrassing errors in my interpretations of certain essays and provided helpful counterpoints to many of my a priori assertions; David Schaberg, who helped my research yield a deeper understanding of what lies behind the etymological and philological complexities of classical Chinese; William Crowell, who has through his attention to historical details added richness to my interpretation of Ban Gus self-representation; and Stephen Durrant, who has given me the lens through which early China can emerge as a real and life-changing place.

Discourse with friends and colleaguesMatthew Wells, Eric Cunningham, and He Jianjunat Oregon have added much to this study. Others have commented on my work at various academic meetings, and I owe them my thanksDavid Knechtges, Paul Kroll, Robert Joe Cutter, Marten Kern, Che Ruxun, and Ken Brashier, to name a few. Jonathan Brooks has offered very helpful comments on my manuscript. I also thank my friends and colleagues at The University of Alabama for their support and assistance, especially Seth Panitch. I am grateful, also, for the generous financial gifts I have received from the J. William Fulbright, NSEP David L. Boren, and Research Advisory grants. I am indebted to the Rare Books Archives and the Center for Chinese Studies at the National Central Library, in Taibei, Taiwan, for providing me with an office and opening their repositories to me. The Southeast Review of Asian Studies has kindly granted permission to include my translation of Ban Biaos General Remarks on Historiography. I have had frequent recourse to the editorial advice of Leland and Carol Roth, the latter whose pen has left more red marks on this draft than I have left on any student paper I have ever graded. Also, I thank my parents, James and Shirley, and my beautiful, too quickly growing daughter, Cassandra, for being happy distractions during times of stress. My greatest debt goes to my wife, Amanda, who has patiently listened to countless readings of passages in this text and rendered needed corrections. In the process of transforming this work from draft to book, Amanda has given her tireless support.

Prologue

American architect Ralph Adams Cram (18631942) once said, We must return for the fire to other centuries, since a night intervened between our fathers time and ours wherein the light was not. The intellectual and material worlds throughout history have been divided at various times. There are those who enthusiastically welcome the ideal of progress, happily dismantling the oppressive and funereal vestiges of the past. Such a view, although not without some occasionally less pejorative reflections on the past, is expressed well in the final chapter of Edward Gibbons (17371794) The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire , where he asserted, All that is human must retrograde if it do not advance. Others, like Cram, lamented the present for having strayed too far from its origins; modernity is as a plant cut off at its base, no longer organically growing from its former roots. The recording of Chinese history in its early stages, perhaps the writing of history over the course of time, is marked by an impulse to hearken to the light of our fathers time and the necessity to advance. Worldviews also influence the historians pen, that is, his or her beliefs and ideals color how the past is judged and how that past will be colored in the present.

This book is a response to what I see as the unfortunate tendency to read historical records merely as deposits of information while relegating the authors of those records to the margins, if not to a place entirely out of mind. Early Chinese historians such as Sima Qian

(145c. 86 BC) and Ban Gu

(3292) did not simply write objective histories of past events; the object of history was never impartial to Han

(206 BC220) historians. For them, the past was often accepted as an irrefutably golden era from which human institutions had wandered; or in the language of early philosophers and historians, the teachings of the sages ( shengren

) of high antiquity ( shanggu

) had decayed ( shuai

). There is, therefore, always a connection between the past one writes about and the present one lives within, for when one employs the events of the past to shed light on those of the present, one is always influenced by ones historical context.

Despite this disjunction, I remain unconvinced by recent assertions that all records of the past are necessarily mythologized by the historians cultural present by which he or she is encumbered. Admitting the usefulness of much of Edward Saids ideashis argument that all narrative representations of history are merely a re-presence of the past, that is, that they can never truthfully recover an accurate view of the pastis not born out by the rather frequent archeological discoveries that enforce the vision of early China provided to modern scholars by ancient historians. I do, however, entertain Saids point here and there nonetheless. In addition, to read someones work is to read their words, and barring textual corruptions precipitated by centuries of accretions and lacunae, by reading their words present readers are, in a significant way, accessing their thoughts and ideas. But even so, texts change over time either in the mind of their authors or in the hands of their editors. The goal of this book, then, is to carefully read the writings of the Eastern Han

(145c. 86 BC) and Ban Gu

(145c. 86 BC) and Ban Gu  (3292) did not simply write objective histories of past events; the object of history was never impartial to Han

(3292) did not simply write objective histories of past events; the object of history was never impartial to Han  (206 BC220) historians. For them, the past was often accepted as an irrefutably golden era from which human institutions had wandered; or in the language of early philosophers and historians, the teachings of the sages ( shengren

(206 BC220) historians. For them, the past was often accepted as an irrefutably golden era from which human institutions had wandered; or in the language of early philosophers and historians, the teachings of the sages ( shengren  ) of high antiquity ( shanggu

) of high antiquity ( shanggu  ) had decayed ( shuai

) had decayed ( shuai  ). There is, therefore, always a connection between the past one writes about and the present one lives within, for when one employs the events of the past to shed light on those of the present, one is always influenced by ones historical context.

). There is, therefore, always a connection between the past one writes about and the present one lives within, for when one employs the events of the past to shed light on those of the present, one is always influenced by ones historical context.