Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

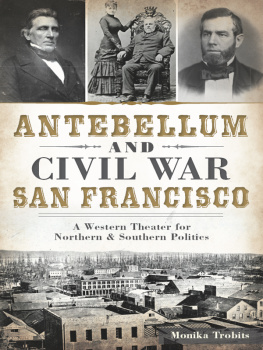

Copyright 2014 by Monika Trobits

All rights reserved

Front cover, top left: William M. Gwin. Library of Congress.

Front cover, top middle: Lillie Hitchcock and Dr. Charles Hitchcock. San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.

Front cover, top right: David C. Broderick. Library of Congress.

Front cover, bottom: An 1851 panorama of San Francisco and Yerba Buena Cove looking toward the East Bay. San Francisco Maritime NHP, A11.7881.2n.

First published 2014

e-book edition 2014

ISBN 978.1.62584.960.1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014953161

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.427.4

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Contents

Introduction

From the era of the British colonies to the emergence of the American states, the eastern seaboard had been both slave and free. As the country grew westward, that trend continued but became increasingly more and more complicated. The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 doubled the size of the country and created new debates over the westward expansion of slavery. As Northerners and Southerners began slowly moving into the vast Louisiana Territory, merging with the longtime French, Spanish and tribal residents, it would take congressional acts and compromises to maintain the increasingly shaky equilibrium. Forty-five years later, American acquisition of Mexican Alta California and the simultaneous discovery of gold created an unprecedented rush to the West, raising new questions about the expansion of slavery. The current state of California would be carved out of that acquisition amid congressional arguments both in favor of and against extending slavery to the West.

By the mid-nineteenth century, Southern interests in Congress, which represented slaveholding aristocrats, appeared to be paralleling the British Parliament of the eighteenth century. Parliament had imposed controls and restrictions on its thirteen colonies in North America, the very same colonies that would emerge as the East Coast states of the North and the South. But did Congress want to risk driving Americans to rebellion, as had happened in 1776, resulting in a long, drawn-out war? A civil war would be even worse than a revolution. Americans would be fighting one another during emotionally charged, passion-filled, bloody battles that would ravage the landscape and its residents. Many Americans could see the similarities between the United States of the 1850s and the British colonies in the 1770s. Some could see only the economics of the increasingly worn-out fields in the East as decades of plantation-style farming took its toll. To them, the need to continue extending slavery farther and farther west was obvious and justified. A good number, however, believed that each individual state should decide the question for itself. While Congress debated back and forth, those already in California in 1849 took matters into their own hands and did just that.

More than two thousand miles separated California from the political, social and economic dynamics of the states that comprised the North and the South. It would attract those dynamics to the West as thousands of highly motivated individuals steadily poured into San Francisco from regions east of the Mississippi River, destined for the nearby gold fields. The antebellum era in the eastern states coincided with the gold rush era in California, and the social order that developed out of this gold rush migration in many ways represented a microcosm of the United States in the 1850s. These American gold seekers brought with them their respective politics and their attitudes reflecting the economic and social realities of either the industrial, money-oriented North or the social status consciousness and chivalry of the agricultural South. Their migration would introduce both the New York and Southern-style of politics to San Francisco beginning in 1849. This divergence would play out in interesting ways over the coming decade, i.e., through feuds, duels and the loss and gain of political control. These American newcomers would join the very diverse collection of individuals already in California who had arrived the prior year, during previous decades or over the course of many centuries.

San Francisco became the new El Dorado. What had been a small town of fewer than one thousand residents in 1848 would burst into a booming city of thirty thousand within two years; an instant city, it was called. While a significant number of its transient residents were foreigners from various continents, the Americans from the Atlantic states would dominate. If East Coasters thought they had moved away from the heated slavery question by going west, they were wrong, as it followed them to the shores of the Pacific. The rush for Californias mineral riches of gold and, later, silver during the antebellum period would force some Argonauts to choose between the wealth of the West and loyalty to the South. It also forced Congress and the nation to confront the future of the Souths peculiar institution and its application in the West. These issues pushed the United States toward its second American revolution, the Civil War.

The West would prove to be more than a distant relative to the squabbling siblings of the North and the South. Following the war, it would be where the flagging, puritanical American work ethic of the East would be reborn as the energized, entrepreneurial California dream of the West. San Francisco would become the Queen City of Americas West, and California would emerge as the Empire State of the Pacific.

One important point that readers should bear in mind is with respect to political parties as they are discussed in this book. In both platform and philosophy, the Democrats and Republicans of the mid-nineteenth century were dramatically different from the parties bearing the same names in the modern era.

The idea for this book came about because of my continued interest in San Franciscos early years, my longtime love of the theater and my wanting to know more about the impact of the Civil War in the West. What brought it all together for me was my reading about the Booth acting family and how antebellum issues affected them. In many respects, the Booths are the bookends for the story in this book.

In the interest of the past meeting with the present, I have sought to connect San Franciscos antebellum and Civil War days with present-day life in the city by highlighting the remnants from those decisive, unsettling decades of the mid-nineteenth century. I do much the same through a walking tour that I have developed in conjunction with this book. More information on that tour may be found on my website: www.sanfranciscojourneys.com.

Monika Trobits

San Francisco, California

October 2014

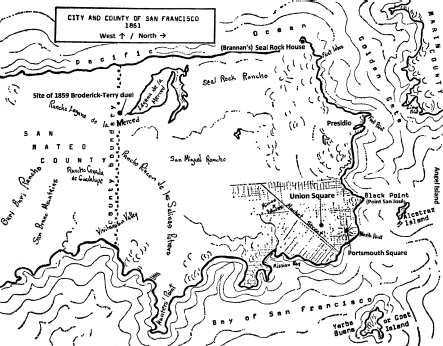

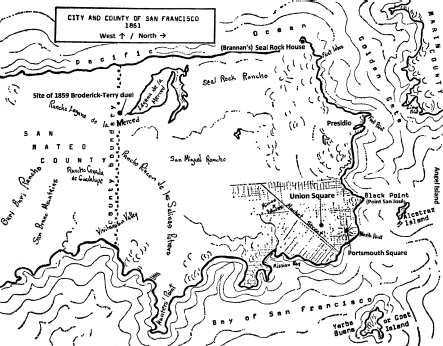

An 1861 map of San Francisco annotated by the author. Courtesy Rather Press Collection, Sanoian Special Collections Library, California State University, Fresno

Next page