ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I stand upon the shoulders and owe grateful appreciation to a myriad of supporters, more than my allotted space allows me to mention. To the Western States Jewish History Association, the Taube Institute for Jewish Life and Culture, and the Jewish Community Federation of San Francisco for their grants that permitted me to tap libraries and museums near and far. To Seymour Fromer, retired executive director and longtime friend; to Aaron T. Kornblum, archivist; and to James Leventhal, director of development, who opened to me the richness of the Western Jewish History Center of the Judah L. Magnes Museum (WJHC/JLMM). To my academic advisor, Dr. Marc Dollinger, the Richard and Rhoda Goldman Endowed Chair in Jewish Studies and Social Responsibility at San Francisco State University; and to my readers John Rothmann, Frances Dinkelspiel, Rabbi Stephen S. Pearce of Temple Emanu-El, and Dr. Stanley Tick, retired from the English Department of San Francisco State University, for their insightful observations. To chief executive officer Thomas Dine of the Jewish Community Federation, executive director Phyllis Cook of the Jewish Community Endowment Fund, the numerous professionals within the Federation, and those working in other Jewish organizations, I offer a heartfelt todah rabbah. To Dr. Jonathan Schwartz, the staff, and the volunteers of the Jewish Community Library of the Bureau of Jewish Education who guided me to resources. To executive director Nathan Levine and communications manager Aaron Rosenthal of the Jewish Community Center, who gave generously of their advice and time. To Paula Freedman, archivist of Temple Emanu-El, and to Hallie Baron, director of marketing and communications of the Jewish Community Federation, who with especial graciousness made available to me their picture files. To pioneer historian Dr. Fred Rosenbaum for our conversations, which led to my undertaking this project. To my editor, John Poultney, and the staff at Arcadia Publishing, who were ever present offering guidance and lending a needed hand. To my next-door neighbor, youthful and knowledgeable Stacy Passman, whose mastery of the computer and understanding of what, for me, is the new world of electronic publishing made possible the finished manuscript. To the many who dug into drawers and closets for their personal family photographs. And on and on goes my list of supporters, who, though unnamed, have my eternal gratitude.

EPILOGUE

Todays Jews are significantly involved in philanthropy. In the Jewish community, their beneficence is omnipresent. In the general community, their generosity and leadership are to be found at the San Francisco Symphony, Ballet, and Opera; at the Museum of Modern Art; at the Public Library; at hospitals and welfare centers; and at hosts of other organizations and institutions. The following, courtesy of the Jewish Community Foundation, is a 2006 partial list of major San Francisco Bay Area Jewish Foundations:

Gerson and Barbara Bakar Foundation

Columbia Foundation

Helen Diller Family Foundation

David B. Gold Foundation

Richard and Rhoda Goldman Foundation

Eucalyptus Foundation

Friend Family Foundation

Friedman Family Foundation

Miriam and Peter Haas Foundation

Walter and Elise Haas Foundation

Hellman Family FoundationKoret Foundation

Laura and Gary Lauder Philanthropic Fund

Levine-Lent Fund

Alexander M. and June L. Maisin Foundation

Bernard Osher Jewish Philanthropic Foundation

Claude and Louise Rosenberg Foundation

Richard and Barbara Rosenberg Philanthropic Fund

Albert and Janet Schultz Supporting Foundation

Saal Family Foundation

Mae and Benjamin Swig Supporting Foundation

Taube Foundation for Jewish Life and Culture

INHERITING THE PAST

PARTICIPATING IN THE PRESENT

BUILDING THE FUTURE

Find more books like this at

www.imagesofamerica.com

Search for your hometown history, your old

stomping grounds, and EVEN your favorite sports team.

One

PIONEERS AMONG PIONEERS

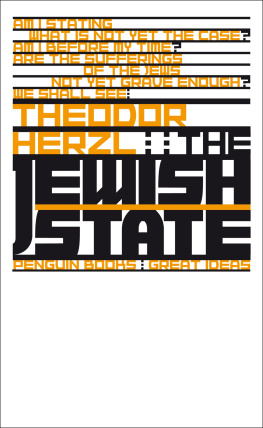

The California gold rush was an odyssey into an unknown land for everybody, but the Jewish immigration to California at this time was a unique phenomenon. Jews had migrated to new lands before, but, for the most part, they had settled in metropolitan areas or in smaller towns where there were good prospects of earning a livelihood. They did not know what to expect when they reached California. The claims of travel guides proved to be exaggerated. In 1849, there were no large cities at the mines, only a few small towns; means of transportation from San Francisco to the mountains were poor; and the gold was usually not easily obtained. But the Jews came in large numbers to this unknown land on the strength of the same rumors that motivated the Gentiles. Statistics for the early years are not available, but there are indications that by 1860 there were possibly as many as 962 Jewish males in San Francisco.

Robert E. Levinson, The Jews in the California Gold Rush , page 6

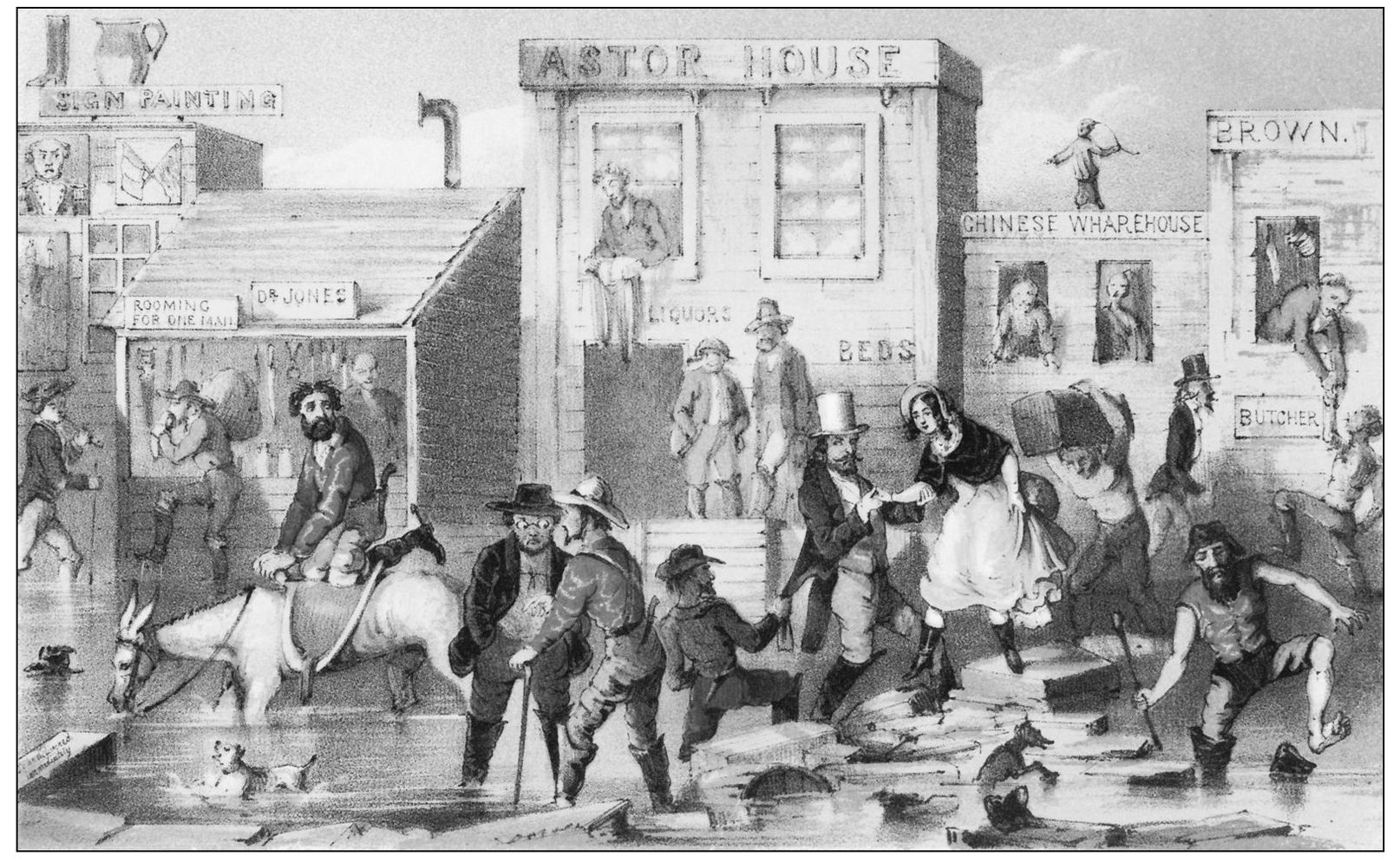

In 1846, Yerba Buena was a quiet Mexican village of approximately 200 people. In 1847, its name was changed to San Francisco, and the following year, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ceded California to the United States. By 1849, San Francisco became a sprawling instant city of canvas tents and flimsy shacks, quickly ravaged by fires, floods and sandstorms; infested with rats and vermin; and subject to cholera. Gang warfare and murders overflowed onto the muddy streets. (Courtesy Bancroft Library.)

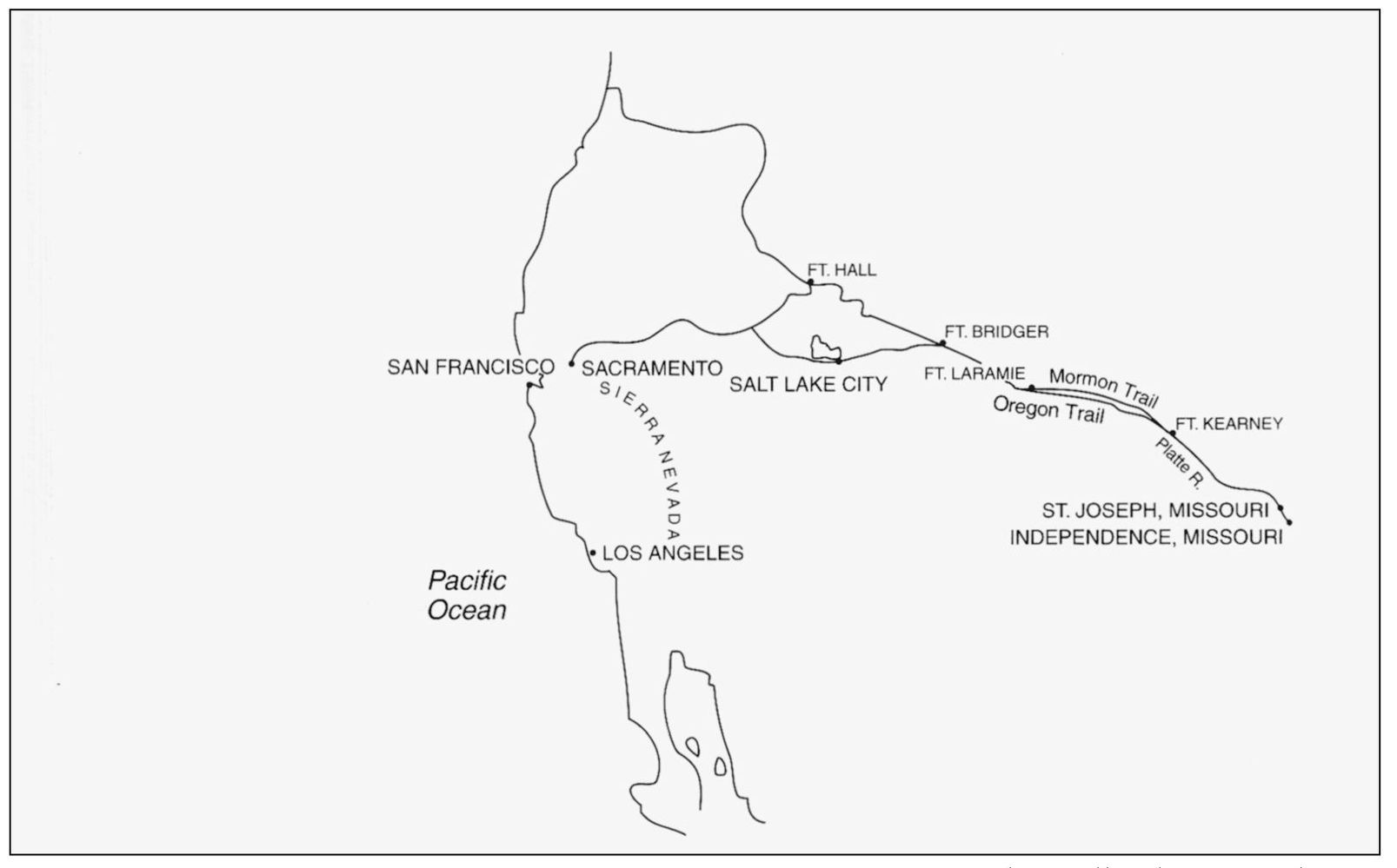

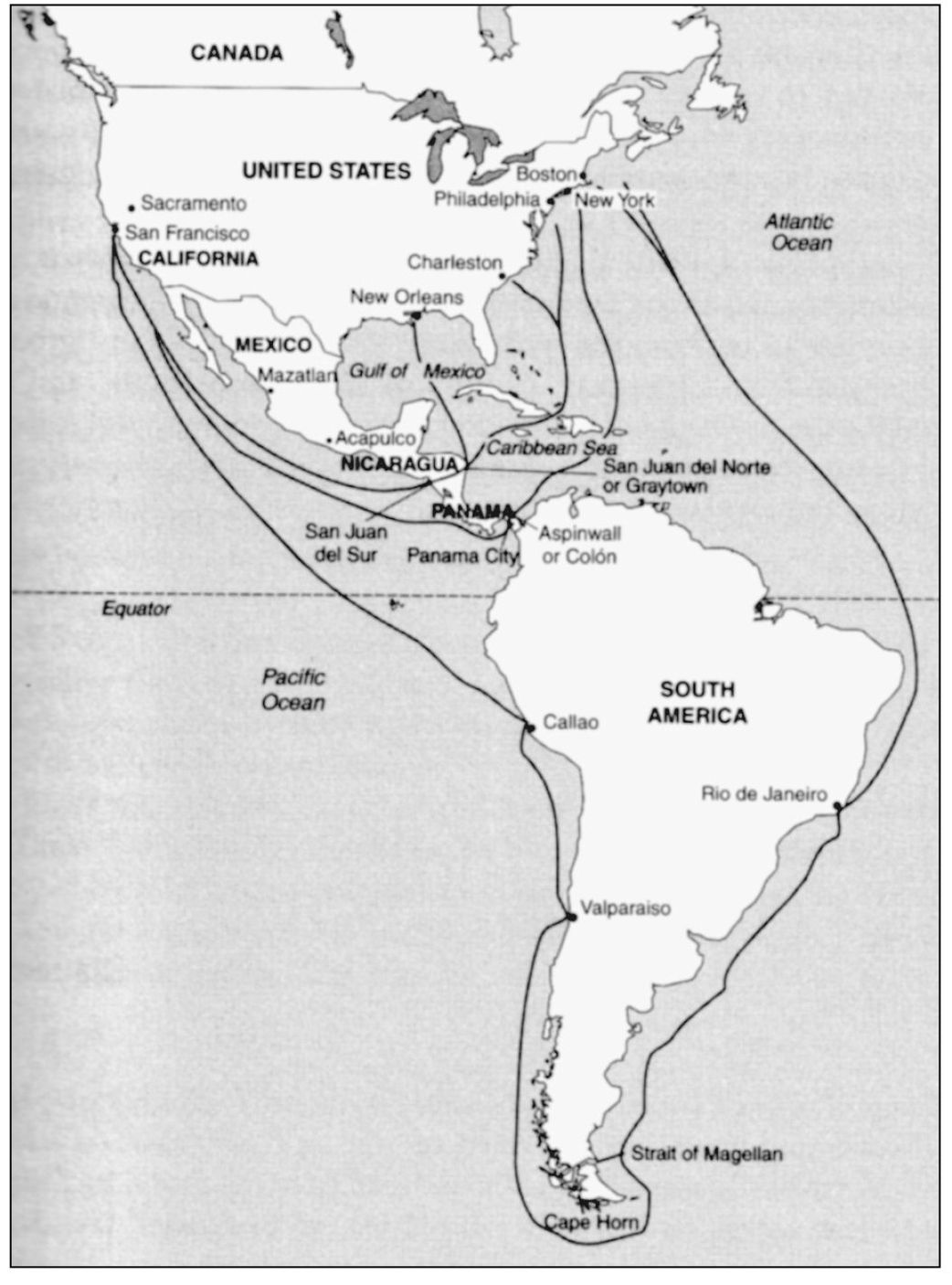

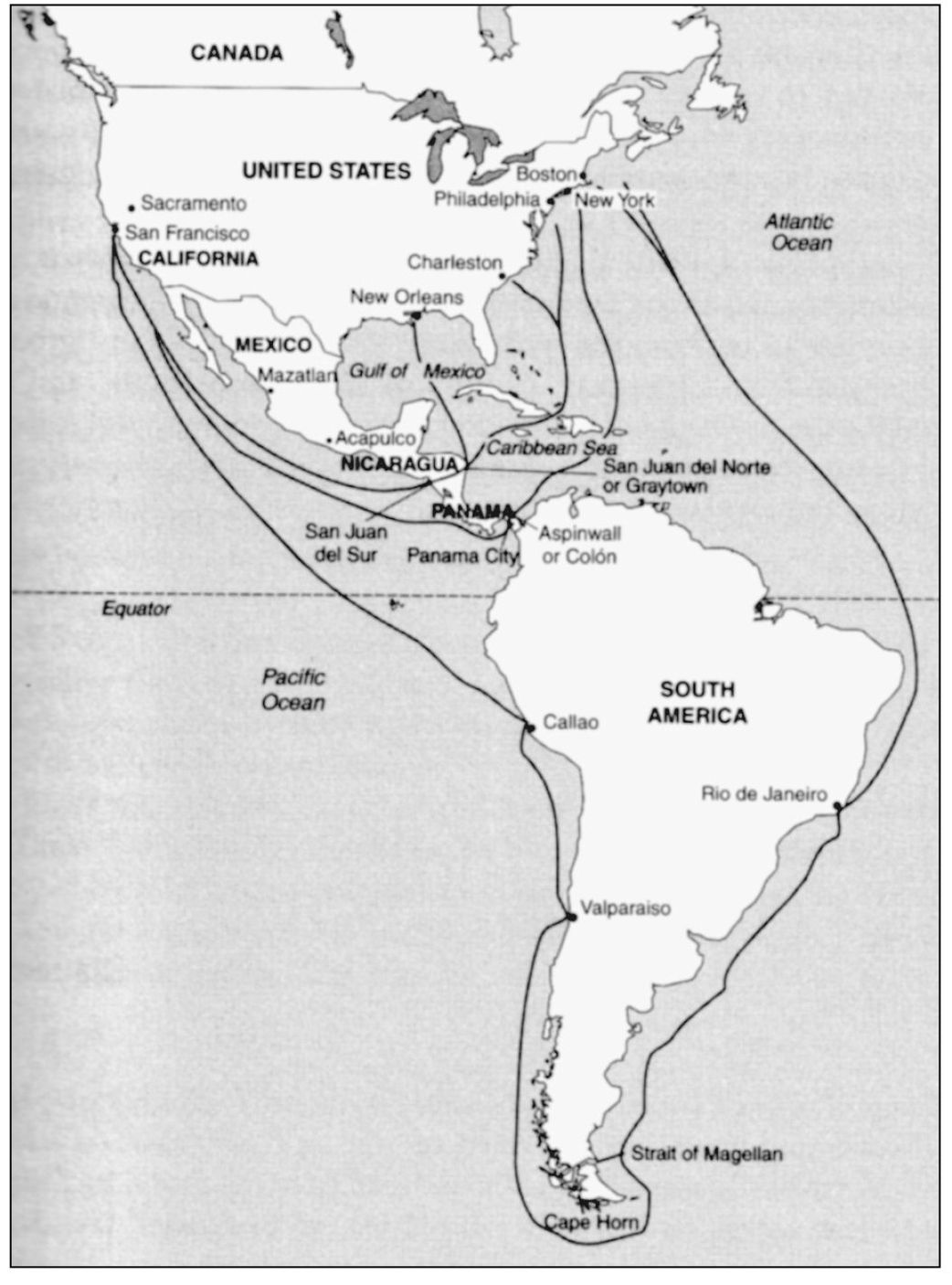

People of all colors, social classes, nationalities, and religions came by every conceivable meansby wagon or on foot across mainland North America, by ship around Cape Horn, or by passage across the Isthmus of Panama or Nicaragua. All too often, when they undertook their journey, they did not realize that the gold fields were over 100 miles inland and that arrival at San Franciscos Golden Gate was just the beginning of another arduous undertaking. The map above shows 1800s overland trails to California from the eastern United States. The lower map indicates gold rushera sea routes to California from the eastern United States.(Courtesy Wayne State University Press.)

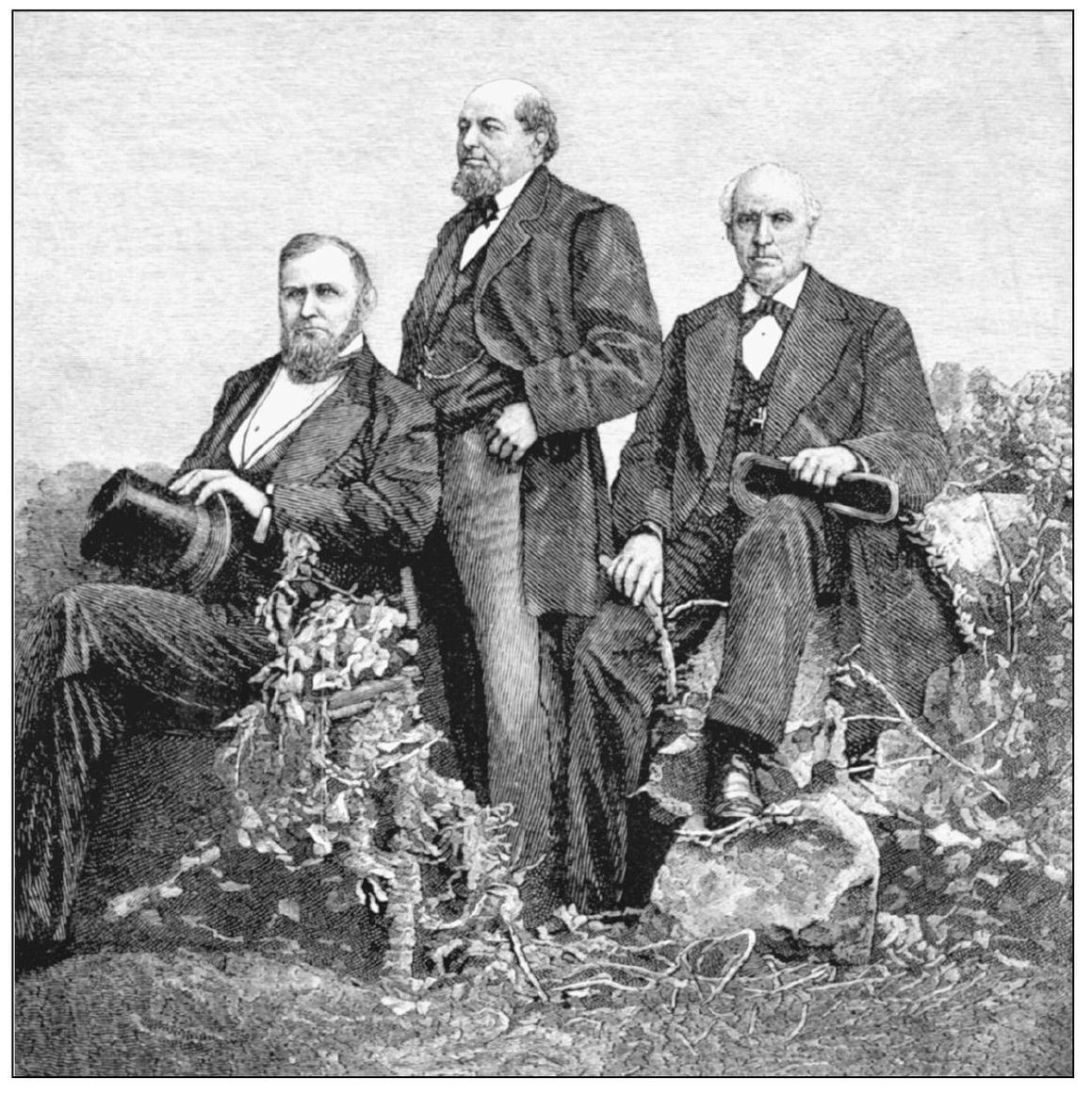

From left to right, Dr. McDonald, Dr. Louis Sloss, and Dr. Swift joined a wagon train to cross mainland North America. When cholera broke out, they left the train as soon as their medical services could be spared, believing that their packhorses could travel much easier and faster than loaded wagons. They arrived safely in California. (Courtesy Bancroft Library.)