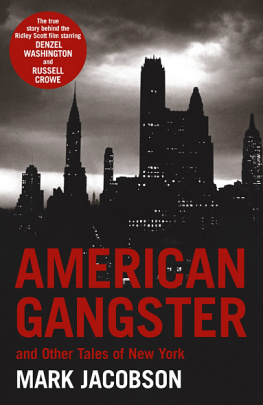

AMERICAN GANGSTER

MARC JACOBSON is the author of 12,000 Miles in the Nick of Time: A Semi-Dysfunctional Family Circumnavigates the Globe, Teenage Hipster in the Modern World, and the novels Gojiro and Everyone and No One. He has been a contributing editor to Rolling Stone, Esquire, Village Voice and New York Magazine.

Also by Mark Jacobson

Novels

Gojiro

Everyone and No One

Non-fiction

Teenage Hipster in the Modern World: From the Birth of Punk to the Land of Bush, Thirty Years of Apocalyptic Journalism

12,000 Miles in the Nick of Time:

A Semi-Dysfunctional Family Circumnavigates the Globe

The KGB Bar Non-fiction Reader (edited)

American Monsters (edited, with Jack Newfield)

AMERICAN GANGSTER and Other Tales of New York

MARK JACOBSON

Foreword by Richard Price

Atlantic Books

London

First published in the United States of America in 2007 by

Grove/Atlantic Inc.

First published in paperback in Great Britain in 2007 by

Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove/Atlantic Ltd.

This electronic edition published in Greate Britain in 2009 by

Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove/Atlantic Ltd.

Copyright Mark Jacobson 2007

Foreword copyright Richard Price 2007

The moral right of Mark Jacobson to be identified as the

author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Acts of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any

form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying,

recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both

the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The Publishers will be pleased to make good any

omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at

the earliest opportunity.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the

British Library.

ISBN: 978 1 84887 265 3

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

Contents

Foreword

I've always felt that the only subjects worth writing about were those that intimidated me, and the only writers worth emulating were those who left me feeling the same way. I've felt intimidated by Mark Jacobson since 1977 when I first read "Ghost Shadows on Chinatown Streets," his portrait of gang leader Nicky Lui, in the Village Voice. I remember being overwhelmed by both Jacobson's reporting skill and his intrepidness, empathizing with his attraction to the subject; could see myself attempting something like that if I had both the writing chops and the nerve. It was one of the most humbling and enticing reading experiences of my life, and in many ways set me on the path to at least three novels.

Jacobson belongs to that great bloodline of New York street writers from Stephen Crane to Hutchins Hapgood to Joseph Mitchell, John McNulty, and A. J. Liebling, through Jimmy Breslin and Pete Hamill, and now to himself and very few others (his friend and peer Michael Daly comes to mind). Jacobson is drawn to these streets and to those who rose from them: the outlaws, the visionaries, the hustlers, and the oddballs. His voice is often sardonic, bemused, and a little in awe of the man before him. Like a judo master, he knows how to step off and let the force of these personalities hoist their own banners or dig their own graves. But even in the case of the most heinous of men, Jacobson's ability to unearth some saving grace, some charm, or simply a shred of sympathetic humanity in the bastard is unfailing.

From heroin kingpin Frank Lucas to the Dalai Lama, Jacobson's fact-gathering is impeccable, his presentation of the Big Picture plain as day, the conversations (you can't really call them "interviews") often hilarious. Most important, though, his love for this world, these people, is apparent in every nuance, every finely observed detail. His is the song of the workingman, the immigrant, the street cat, the cryptician with more crazy-eights than aces up his sleeve, and Jacobson knows that the bottom line for this kind of profiling is self-recognition; each character, each sharply etched detail in some way bringing home not only the subject, but the reader and author, too.

Richard Price

Never Bored: The American Gangster, the Big City, and Me

I was born in New York City in the baby boom year of 1948 and lived here most of my life. I started my journalism career back in the middle 1970s, writing more often than not about New York. There have been ups and downs over the past thirty years, but I can't say I have ever been bored. After all, the Naked City is supposed to have eight million stories and, as a magazine writer, I only need about ten good ones a year. So I can afford to be picky. Whether I've been picky enoughor managed to tell those stories well enoughyou can decide for yourself by thumbing through this book. That said, some stories are just winners, fresh-out-of-the-blocks winners. The saga of Frank Lucas, Harlem drug dealer, reputed killer, and general all-around enemy of the people, was one of those stories.

An odd thing about the genesis of my involvement with Lucas is that I'd always been under the impression he was something of an urban myth. That was my opinion when Lucas's name came up in a conversation I was having half a dozen years ago with my good friend, the late Jack Newfield. Newfield said he'd seen Nick Pileggi, the classic pre-Internet New York City magazine writer who had been smart enough to get out at the right time, making untold fortunes writing movies like Goodfellas. Nick had mentioned to Jack that Lucas was alive and living in New Jersey.

"You mean, Frank Lucas, the guy with the body bags?" I asked Newfield, who said, yeah, one and the same. This was a surprise. Anyone who had their ear to the ground during the fiscal crisis years of the 1970s, those Fear City times when New York appeared to be falling apart at the seams, remembered the ghoulish story of thousands of pounds of uncut heroin being smuggled from Southeast Asia in the body bags of American soldiers killed in the Vietnam War. The doomsday metaphordeath arriving wrapped inside of deathwas hard to beat, but this couldn't really be true, could it?

This was one of the first things I asked Lucas when, after much hunting, I located him in downtown Newark. "Did you really smuggle dope in the body bags?" I asked Frank, then in his late sixties, living in a beat-up project apartment and driving an even more beat-up 1979 Caddy with a bad transmission.

"Fuck no," responded Lucas, taking great offense. He never put any heroin into the body bag of a GI. Nor did he ever stuff kilos of dope into the body cavities of the dead soldiers, as some law enforcement officials had contended. These were disgusting, slanderous stories, Lucas protested.

"We smuggled the dope in the soldiers' coffins," Lucas roared, setting the record straight. "Coffins, not bags!"

This was a large distinction, Frank contended. He and his fellow "Country Boys" (he only hired family members or residents of his backwoods North Carolina hometown) would never be so sloppy as to toss good dope into a dead guy's body bag. They took the trouble to contact highly skilled carpenters to construct false bottoms for soldiers' coffins. It was inside these secret compartments that Lucas shipped the heroin that would addict who knows how many poor suckers. "Who the hell is gonna look in a soldier's coffin," Lucas chortled rhetorically, maintaining that his insistence on careful workmanship showed proper deference to those who had given their life for their country.