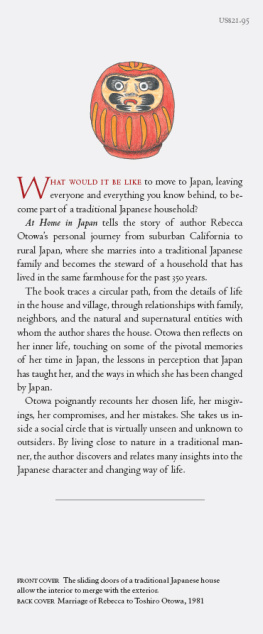

H. S. Williams was born in Melbourne, Australia, in 1898. He was headed for a scientific career; at first as a junior analyst in the Commonwealth Laboratory of Australia, then as a medical student at the Melbourne University. He was already seriously interested in the Japanese language and history as a hobby, and at the end of his third year in medicine he came to Japan on a holiday.

On arrival in Japan, an advertisement in the former Japan Advertiser caught his attention, and by replying to it he hoped to have the opportunity of seeing inside one of the hongs in Japan of which he had read so much. He later went for an interview, confident in the belief that he would not be engaged. To his great dismay he found that he was hired as an assistant in the old Scottish hong of Findlay Richardson & Co. Ltd. He thereupon temporarily postponed his return to Australia, but eventually decided to give up his career and make his future in Japan.

Later Williams became managing director of the silk firm of Cooper Findlay & Co. Ltd.

In 1941 he left Japan and enlisted in the Australian Army. He attained the rank of major and saw service in Africa, the Pacific, and Burma. He arrived back in Japan a few weeks after the surrender as a member of the Occupation Forces, and remained in the Australian Army in Japan until 1949 when he resumed his business career.

H. S. Williams is now Managing Director of A. Cameron & Co. Ltd. and sole Trustee of the famous James Estate at Shioya, near Kobe.

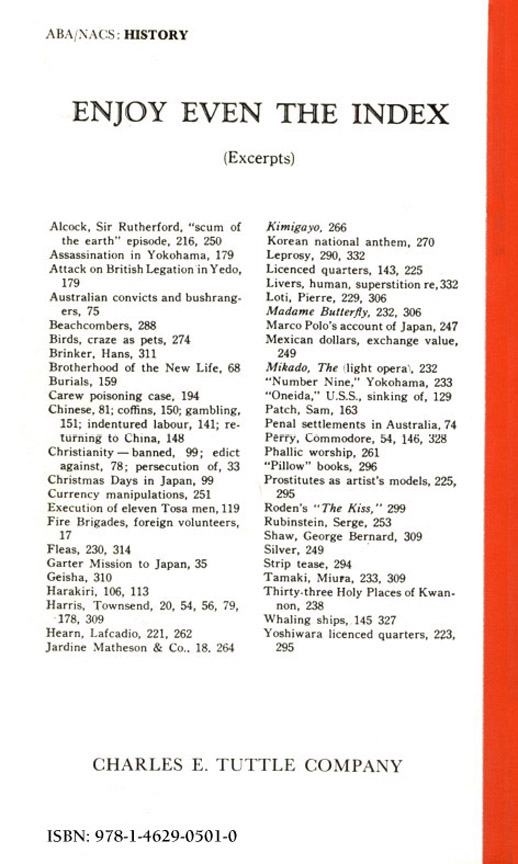

In 1953 he commenced writing historical articles for various publications abroad, and for the Mainichi in a series entitled "Shades of the Past," out of which writings this book was born.

OFFICIAL

SECRETS

With constabulary duties to be done, to be done, The policeman's lot is not a happy one.

"The Pirates of Penzance"

In an article which was published recently, I commiserated with the consuls in Japan of nearly a hundred years ago, who, in addition to their regular consular duties, often had to play the parts of a judge, accountant, assessor, magistrate, arbitrator, coroner, jailer and turnkey.

Surprise having been expressed in some quarters at my statement, and doubts in others as to its accuracy, I felt sufficiently impelled to embark upon a more detailed research into those fabulous days. I soon had evidence that some consuls performed all those functions, plus a few more, for example during times of stress and emergency, and in the absence of adequate staff, even more bizarre duties such as inspector of brothels and nuisances, postmaster, and "Right Hose."

The last mentioned duty was of an extra-curricular nature, and referred to the consul's position on the local fire-cart!

The local volunteer fire brigades were important entities within the structure of the old treaty-port society. One had to be a person of some substance and respectability, quite apart from wind and muscle, to hold office in such an exclusive body as say the Victorian Volunteer Steam Fire Engine Company of Yokohama of ninety years ago.

A new arrival had to have some "pull"if you will pardon the punto gain office, even such a minor office as "Suction and Split Hose" in that particular lire brigade. After attaining that lowly position, an enthusiast could in course of time gain advancement, becoming in turn "Left Hose," "Right Hose," and finally "Foreman" if he happened to be a born fireman or was one of those persons who just cannot escape getting on in life. The coveted rank of "Foreman" was generally held by a Keswick or some such similar stalwart of one of the princely hongs, provided he had brawn and waist line, and enough wind to run a mile.

Pulling the firecart was thirsty work, and putting out fires was wet work, which perhaps explains why the annual dinnersstag of courseof the volunteer fire brigades were both strenuous and wet affairs!

"Begad, Sir, last week at the fire over at that house near Creekside, 'Suction and Split Hose' sploshed so much water over the girls that their kimono clung to their figures like chemises. Poor show! Poor show!" boomed Foreman Keswick of Jardines at one of those annual dinners.

However to return to the subject of this article, the doubts which were expressed as to whether consuls, and particularly British consuls, ever had to perform the various duties which I had ascribed to them, were a challenge which caused me to search among the papers and records which may still be found at the bottom of old oak chests, in the dusty cellars of some libraries, and in the bookcases of some of those bearded and wheezy antiquarians and bibliophiles who seldom emerge outdoorsa search which extended into two continents.

In quoting verbatim as I now shallwithout permissionfrom the despatches of Queen Victoria's Consul at Nagasaki in the years 1859-1863, I do not believe I am betraying any very important national secrets. My defence can be that none of those despatches were marked "Top Secret"for the reason possibly that the expression had not then been invented!

Consul Morrison at Nagasaki, the second gentleman to hold that post, arrived there on 8th August, 1859, and it is interesting to note that his first four despatches to the Legation in Yedo were on routine matters, after which he promptly got down to drawing attention to " the low rate of salary which is attached to the office I hold " After admitting that fish and fowl were comparatively cheap and drawing attention to his own most abstemious personal habits, he came to the point:

I would take the liberty to urge that some compensation more than bare subsistence is due, in consideration of an exile to the extremity of the Earth,of banishment from society and from the relations of Home, and exposure to discomforts and privations difficult to depict and cruel to endure. say nothing of the climate, which is for some months in every year destructive to health and even to property, or of the water we have to use, which at this port is so bad as to be almost poisonous. Neither do I dwell on the important and harassing duties with which a Consul is entrusted....

To cut a long story short it is good to be able to report that this appeal did not fall on unresponsive ears, and that in due course of time this plain speaking consul received an increase in salary which I have no doubt he well deserved.

The Consul, among his multifarious duties, was required to perform some of an accountancy nature, a task he does not seem to have always performed to the satisfaction of his superiors in Yedo, to whom on 21st September, 1859, he addressed the following tart despatch:

I have the honour to acknowledge receipt of your Despatch No. 11 returning the accounts of this Consulate....for correction. I am deprived of the facilities for this work.... I shall not fail, however, to me my best endeavours to put these accounts in a proper state....Allow me to express my gratification at the confidence you entertain that under my supervision the accounts of this Consulate will in future be more satisfactorily rendered.

The Consul's negotiations with the local Governor and other officials are of course dealt with at length, and we find him echoing sentiments not unlike those which U.S. Consul-General Harris had expressed, although in more restrained tones. In Despatch No. 17 on 21st September, 1859, he informed the Legation in Yedo:

I have discovered that unhappily no reliance whatever is to be placed on the most solemn assurance of Japanese....

As was Harris, so also was Morrison exasperated at the uniform fate of his many representations to the Japanese authorities, most of which were pigeonholed on the excuse that instructions from the central government in Yedo would have to be awaited, a slow-motion procedure which rarely reached finality.