Table of Contents

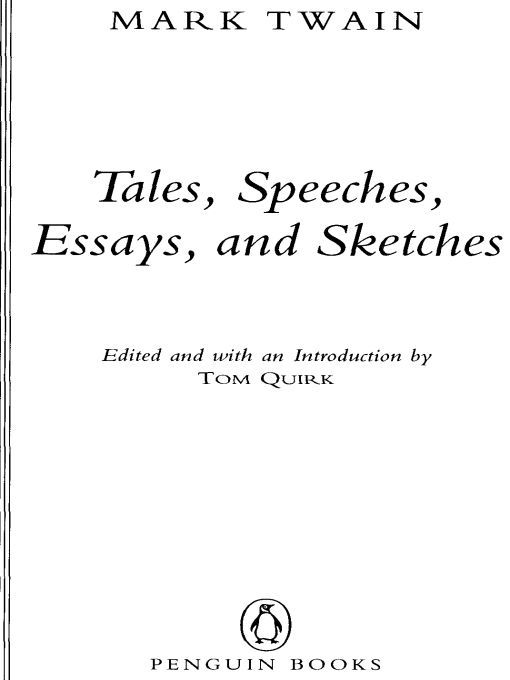

PENGUIN CLASSICS

TALES, SPEECHES, ESSAYS, AND SKETCHES

Samuel Langhome Clemens was born on November 30, 1835, in Florida, Missouri, about forty miles southwest of Hannibal, the Mississippi River town Clemens was to celebrate as Mark Twain. In 1853 he left home, earning a living as an itinerant typesetter, and four years later became an apprentice pilot on the Mississippi, a career cut short by the outbreak of the Civil War. For five years, as a prospector and a journalist, Clemens lived in Nevada and California. In February 1863 he first used the pseudonym Mark Twain, as the signature to a humorous travel letter; and a trip to Europe and the Holy Land in 1867 became the basis of his first major book, The Innocents Abroad (1869). Roughing It (1872), his account of experiences in the West, was followed by a satirical novel, The Gilded Age (1873), Sketches: New and Old (1875), Tom Sawyer (1876), A Tramp Abroad (1880), The Prince and the Pauper (1882), Life on the Mississippi (1883), and his masterpiece, Huckleberry Finn (1885). Following the publication of A Connecticut Yankee (1889) and Puddnhead Wilson (1894), Twain was compelled by debts to move his family abroad. By 1900 he had completed a round-the-world lecture tour, and, his fortunes mended, he returned to America. He was as celebrated for his white suit and his mane of white hair as he was for his uncompromising stands against injustice and imperialism and for his invariably quoted comments on any subject under the sun. Samuel Clemens died on April 21, 1910.

TOM QUIRK is currently the Catherine Paine Middlebush Professor of English at the University of Missouri-Columbia. He is the author of Melvilles Confidence Man (1982), Bergson and American Culture (1990), and Coming to Grips with Huckleberry Finn (1993). He has edited or co-edited several volumes of criticism on American literature, including Writing the American Classics (1990) and Realism and the Canon (1994).

INTRODUCTION

When Samuel L. Clemens published Letter from Carson City in 1863, he signed the sketch Mark Twain. Clemens had adopted pen names beforeW. Epaminondas Adrastus Per-kins, Thomas Jefferson Snodgrass, Joshbut this was the first time he used the name that would eventually become a registered trademark and a universally recognized literary identity. It was a fateful gesture. Much of the experience that Clemens would use in his later fiction was already behind him, but his career as a professional literary person (as he one time described his almost accidental occupation as a writer) largely lay before him. Sam Clemens had been places and seen things; by his own admission, his early adult life consisted of a string of apprenticeships and misdirected ambitions. Mark Twain took the boy in tow. He offered a young journalists perceptions a point and his wit a barb; he gave a mature mans memories of childhood a literary shape and solidity; he transformed a personal delight in the joke, the hoax, and general mischief-making into a moral point of view; he offered an old man the bitter solace of philosophy. For the persona that was Mark Twain was something more than a mere literary device; it became a means of being in the world and of speaking to that world in ways that Clemens might not venture in his own person.

In part, Samuel Clemens had fame, or at least celebrity, thrust upon him. He sent his jumping frog story east to Artemus Ward in 1865 to be included in a collection Ward was assembling, but the tale he had heard (along with so many others) in a California mining camp and had cast in the familiar mode of the frame tale arrived too late for inclusion. It was published instead in the Saturday Press the same year. The story was an instant success and widely reprinted, and its creator thereafter became a figure of some interest. Inevitably, the Mark Twain available to us now is a diminished presence, however much we instinctively feel ourselves to be his familiar acquaintance.

In his own day, Twain was primarily known as a public personality who also happened to be a writer. The public knew him equally through his lectures and readings, through the more than 300 interviews he granted to intrepid reporters, and through the frequent accounts of his doings and sayings in newspapers and magazines. A whole generation grew up with Mark Twain as a living voice and a responsive and frequently outrageous and outraged critic of the times. Though he spent much of his adult life abroad, as George Ade rightly observed, Americans typically thought of him not as an expatriate but as their trustworthy emissary to the world at large. When he died in 1910, much of the country mourned the loss of a genial companion.

Since that time readers and critics have tried to define Twains significance to American literary culture, to analyze his multiform and largely elusive personality, to somehow recapture the distinctive flavor of his humorous idiom, and to describe the mechanics of his wit. Unlike, say, Herman Melville, whose deep-diving imagination is so aptly linked to the sea, there is nothing especially deep about Twain. Like the Mississippi River itself, he is intricate, shifty, and sometimes treacherous, driven by some strong current of earnestness or indignation; he is complicated, but he is not profound. In an essay written for Harpers and titled simply William Dean Howells, Twain identified the qualities he envied in his friend, and many of them he could claim as his own. But Howellss easy prose, unconfused by cross-currents, eddies, undertows, was not his. It is true that Twain made it his business to have a point and to get to it as unmistakably and forthrightly as possible, but even so, there is nearly always a sly wrinkle or unanticipated snag likely to catch us by surprise. Witness this letter written in 1907 to the editor of the New York Times:

To the Editor

Sir to you, I would like to know what kind of a goddam govment this is that discriminates between two common carriers and makes a goddam railroad charge everybody equal & lets a goddam man charge any goddam price he wants to for his goddam opera box.

W. D. Howells

Tuxedo Park Oct 4

Howells it is an outrage the way the govment is acting so I sent this complaint to N. Y. Times with your name signed because it would have more weight.

Mark

The selections gathered together here are meant to give a comprehensive if somewhat uneven sense of the vast range of Mark Twains short fiction and prose, to disclose not merely the variety of his imaginative invention and diverse talents but the range of his emotional condition as well. As if by instinct, he seems to have been naturally adept in virtually every prose genrethe fable, the sketch, the tale, the anecdote, the maxim, the philosophical dialogue, the essay, the speechand to have understood generic requirements sufficiently to burlesque and satirize them as well. (His An AwfulTerrible Medieval Romance was in the tradition of such popular burlesques that parodied the popular romance in only 500 to 2,500 words; and he indulged in the well-known burlesques of popular poetry and the Shakespearean soliloquy in Huckleberry Finn.) At the same time, his imagination seemed always to outrun literary conventions and accepted forms, as though formal discipline were inimical to thought and expression and unequal to the many moods that motivated him to write. He mastered the frame talea form featuring a story within a storyof the Southwestern humorists easily, but this same form that played upon the comic contrasts between genteel refinement and vernacular coarseness acquired a sudden seriousness when he adapted it to the poignant and accusing story of the former slave Aunt Rachel in A True Story. At any rate, these selections are not designed to give any unitary picture of the man or his work.