CHANNEL

SHORE

Also by Tom Fort

Against the Flow

Downstream

Under the Weather

The Book of Eels

The Grass Is Greener

The Far from Compleat Angler

The A303

First published in Great Britain by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd, 2015

A CBS COMPANY

Copyright 2015 by Tom Fort

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention.

No reproduction without permission.

All rights reserved.

The right of Tom Fort to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All photographs Jason Hawkes

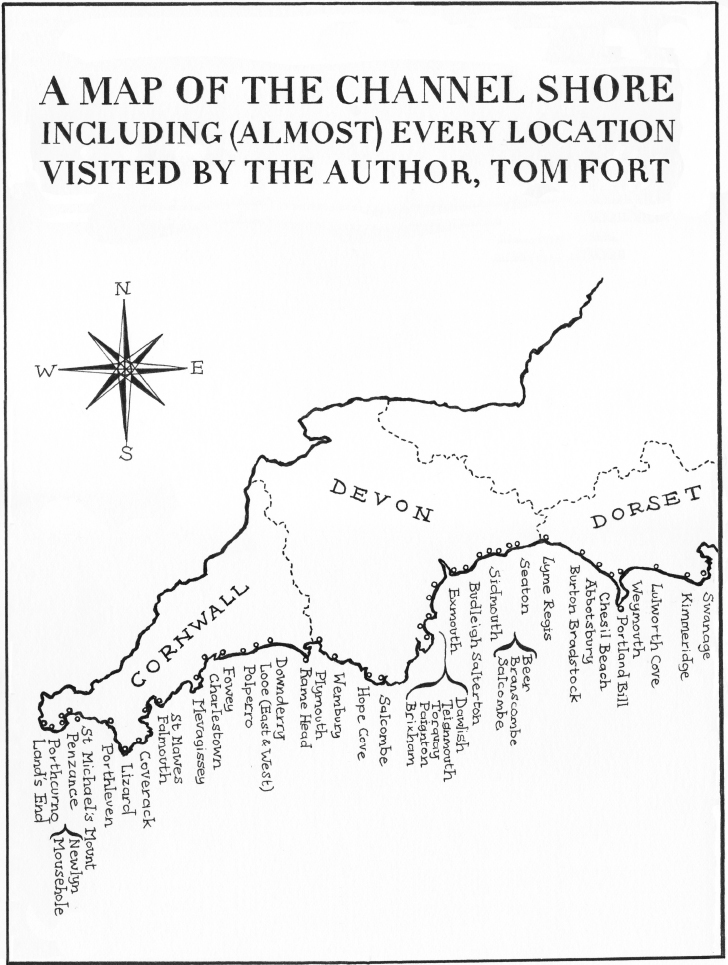

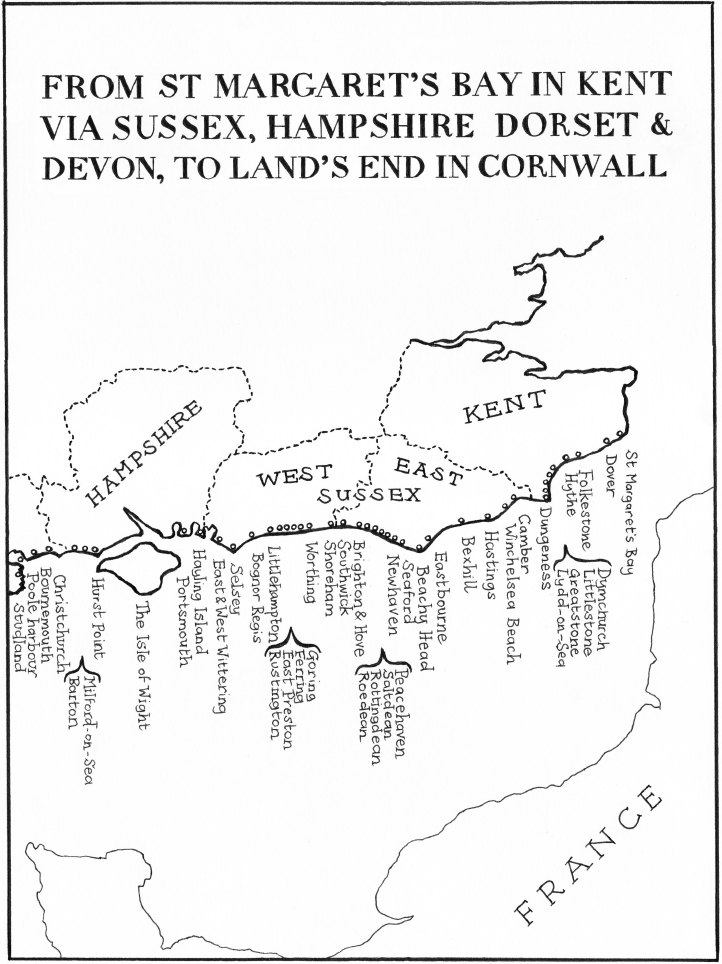

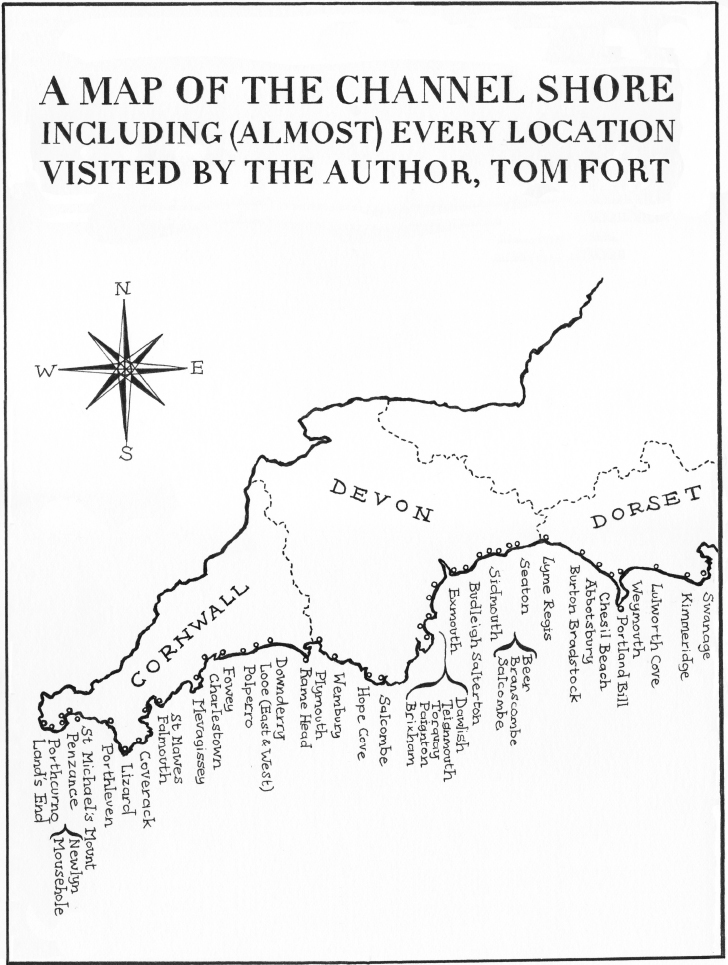

Map Colin Midson

Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

1st Floor

222 Grays Inn Road

London WC1X 8HB

www.simonandschuster.co.uk

Simon & Schuster Australia, Sydney

Simon & Schuster India, New Delhi

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-4711-2972-8

eBook ISBN: 978-1-4711-2974-2

The author and publishers have made all reasonable efforts to contact copyright-holders for permission, and apologise for any omissions or errors in the form of credits given. Corrections may be made to future printings.

Typeset in the UK by M Rules

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

To local historians, past, present and future

C ONTENTS

P REFACE

A July day, and I am in a deckchair under an umbrella on the beach at Bournemouth, near the pier. It is hot, but English hot, not Mediterranean or Aegean; a tolerable, friendly heat. The sky is blue, brushed by high cirrus, the sea pale-blue topaz. The golden sand which runs for miles is parcelled out evenly between low wooden breakwaters.

Everyone is here: the old, in invalid chairs or sunk in deckchairs beneath faded sunhats, toddlers tottering across the sand in disposable nappies sagging with sea water, girls with stomach piercings glinting against nut-brown skin, lads with bony chests in long trunks larking around in inflatables, children on body boards making the best of amiable waves. I watch a dark-skinned woman, fully dressed with just her hands, feet and head showing, dive and twist in the water. She comes out grinning, squeezing the water from her long black hair. In front of us a Polish couple are tenderly intent on their child. A dozen languages mingle over the sand.

Elsewhere the world is tearing itself apart in the normal way. But here the offshore breeze is suffused with the contentment of those lucky enough to be alive and relishing the perfection of an English summers day at the seaside.

A generation ago they told us the seaside holiday was dying and would soon pass away like Empire Day and the Morris Traveller and tinned apricots with evaporated milk and other curious relics. Cheap air travel, package holidays, guaranteed sun, sand and blood-warm sea that was what the British holidaymaker wanted; not shabby amusement arcades, moth-eaten donkeys, rancid fish-and-chips, hatchet-faced boarding-house landladies, a wind-whipped sea the colour of breeze blocks and colder than the Mr Whippy squirming from stainless steel spouts in the ice-cream stalls.

But the seaside holiday clung obstinately to life. People realised that when the sun shone which it tended to do more often and more potently than when I was a little boy, shivering in my shorts at Middleton-on-Sea our beaches could hold their own against those of the Cte this and the Costa that. They were free, open to anyone, easy to get to. The sea was bracing rather than freezing, and although there might be jellyfish, they were not huge and red with terrifying bunches of tentacles, and the water did not spawn banks of bright-green algal jelly. And some of our seaside towns had charms of their own and had learned to please.

I love to be beside the sea, and to be in it, not too deep. But being out on it in anything other than a proper ferryboat or a flat calm makes me tense. I do not like the currents, the depths, the way fierce tides invade at the gallop. Waves with foaming crests make me nervous.

We used to have holidays on a small island on the west coast of Scotland. It was in the mouth of a long sea loch and was consequently swept by vigorous tidal currents, as well as being subject to the normal boisterous weather of those parts. On one occasion we set off down the loch for a picnic. The wind picked up and the water became choppy. At my suggestion we decided to turn back, into the wind and the waves. My sister, sitting in the bow, reported water coming through the planks as well as over the prow. I gripped the handle of the outboard as if the future of the human race depended on it, and we made it back to the bay in front of the house. Looking out half an hour later I observed that the boat had vanished at its mooring, leaving only the painter attached to the buoy as evidence that it had ever existed.

On another occasion I went with one of my brothers to the mainland to get lobsters. Fortunately we were piloted by one of the islands permanent inhabitants, who did it all the time. While we were engaged with the crustacea the wind turned into the east and gathered strength considerably, so that by the time we set off back to the island the waves were charging ahead of us in long, implacable lines, the breaking crests flattened and whipped into the air by the wind. This is exhilarating, my brother shouted as we rode one wave and then the next. I felt ill with fear.

I am a landsman. My nervousness of the sea is not something I am proud of, but its best to accept these limitations. It followed that when I came to write this Channel story it would be from a land-based perspective, of one looking out to sea with feet planted on firm rock, or sand or earth. The idea for it was not mine, but came from a film-maker, Harry Marshall of Icon Films, who wanted to make a sequence of programmes about the Channel and what it means to us, and thought I might make a suitable presenter. The project was eventually aborted the deep thinkers at the BBC decided it would tread ground sacred to the long-running Coast. But by then I had been thoroughly seduced by the prospect of a personal exploration of that strip of land beside the waterway that, more than any other, has formed our sense of who we are.

So I went alone, free from the tyranny of filming, from Kent to Cornwall down Channel. I was curious to know what it was about our Channel shore that was so special and indispensable; that drew some people and held them and called them back even when they had taken themselves off somewhere else. It was pretty straightforward to work out why some like myself chose to take their holidays beside the sea. More interesting, to my way of thinking, were those who chose to live within sight and sound and smell of the Channel shore: some born to it, many others pulled that way later in their lives by an insistent force.

As I made my way south-west over the course of the summer of 2013, I came to appreciate the nature of that force as I never had while just on holiday. Those who take their week or fortnight by the sea, or flit to and from their holiday homes, scrape the surface. If the weather is kind, they are happy; if not, they return home resentful, as if somehow they had been misled or let down. For those who live there, the whole point is the bad weather with the good, the richness of variation, the endless change in mood and colour and texture. They tend to be not so interested in the blatant pleasures of the summer season. They wait for the transients to depart to reclaim their kingdom.

Next page