Janna Levin is a professor of physics and astronomy at Barnard College of Columbia University. She lives in New York City.

ALSO BY JANNA LEVIN

How the Universe Got Its Spots:

Diary of a Finite Time in a Finite Space

To my father

There is no beginning. Ive tried to invent one but it was a lie and I dont want to be a liar. This story will end where it began, in the middle. A triangle or a circle. A closed loop with three points.

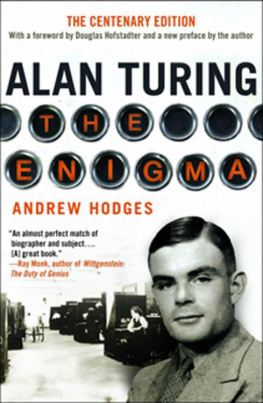

At one apex is a paranoid lunatic, at another is a lonesome outcast: Kurt Gdel, the greatest logician of many centuries; and Alan Turing, the brilliant code breaker and mathematician. Their genius is a testament to our own worth, an antidote to insignificance; and their bounteous flaws are luckless but seemingly natural complements, as though greatness can be doled out only with an equal measure of weakness.

These two people converge in history and diverge in belief. They act out lives that are only tangentially related and deaths that are written for each other, inverted reflections. They are both brilliantly original and outsiders. They are both loyal to reason and to truth. They are both besotted with mathematics. But for all their devotion, mathematics is indifferent, unaltered by any of their dramasGdel's psychotic delusions, Turing's sexuality. One plus one will always be two. Their broken lives are mere anecdotes in the margins of their discoveries. But then their discoveries are evidence of our purpose, and their lives are parables on free will. Against indifference, I want to tell their stories.

Dont our stories matter?

I shouldnt even be here but some things you can only get to in the most awkward ways. Even if I tried to hide it, to lie, the truth is it's still me telling this story. The unsorted catalogue of biographical facts provides nothing without stories with their dents and omissions and sometimes outright lies to create meaning that just wont emerge from the debris of unassembled facts. Because some truths can never be proven by adhering to the rules. So this whole story about Truth is a Lie. The liar says, This is a lie.

I am that liar, the third and final point on the triangle, the weak link, the wobbling hinge, the misaligned vertex. I am meant to carry on from the previous point and give over to the next. But I dont know where to begin. I am standing on a street, in a city. Im going to catch a train. There are people streaming in all directions and one old woman strolling. Will any of us be remembered? Do any of us matter?

This story about truth and logic leads to atheism and mysticism. To despair and suicide. To the future, our past. To the present. So here's a starting point as arbitrary as any because logic does not unfold in time. It exists forever into the past, dictating how the universe began; and forever into the future, our fate already written by the inescapable rules of logic. We can enforce chronology because the linearity of time helps; it gives us roles in the script, a place to start and to end. So here I start. In Vienna. It is the year 1931. This place is as good a place, this time as good a time, as any.

VIENNA, AUSTRIA. 1931

The scene is a coffeehouse. The Caf Josephinum is a smell first, a stinging smell of roasted Turkish beans too heavy to waft on air and so waiting instead for the more powerful current of steam blown off the surface of boiling saucers fomenting to coffee. By merely snorting the vapors out of the air, patrons become overstimulated. The caf appears in the brain as this delicious, muddy scent first, awaking a memory of the shifting room of mirrors secondthe memory nearly as energetic as the actual sight of the room, which appears in the mind only third. The coffee is a fuel to power ideas. A fuel for the anxious hope that the harvest of art and words and logic will be the richest ever because only the most fecund season will see them through the siege of this terrible winter and the siege of that terrible war. Names are made and forgotten. Famous lines are penned, along with not so famous lines. Artists pay their debt with work that colors some walls while other walls fall into an appealing decrepitude. Outside, Vienna deteriorates and rejuvenates in swatches, a motley, poorly tended garden. From out here, the windows of the coffeehouse seem to protect the crowd inside from the elements and the tedium of any given day. Inside, they laugh and smoke and shout and argue and stare and whistle as the milky brew hardens to lace along the lip of their cups.

A group of scientists from the university begin to meet and throw their ideas into the mix with those of artists and novelists and visionaries who rebounded with mania from the depression that follows a nation's defeat. The few grow in number through invitation only. Slowly their members accumulate and concepts clump from the soup of ideas and take shape until the soup deserves a name, so they are called around Europe, and even as far as the United States, the Vienna Circle.

At the center of the Circle is a circle: a clean, round, white marble tabletop. They select the Caf Josephinum precisely for this table. A pen is passed counterclockwise. The first mark is made, an equation applied directly to the tabletop, a slash of black ink across the marble, a mathematical sentence amid the splatters. They all read the equation, homing in on the meaning amid the disordered drops. Mathematics is visual not auditory. They argue with their voices but more pointedly with their pens. They stain the marble with rays of symbolic logic in juicy black pigment that very nearly washes away.