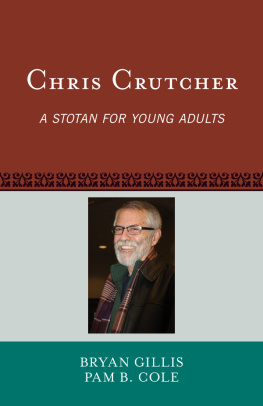

I GREW UP RIDING A ROCKET . If legendary rocket man Wernher von Braun could have harnessed the power of my meteoric temper, wed have beaten the Russians into space by a good six months. The bits of evidence lay in the wake of my explosive impulsivity like trailer-house pieces behind Hurricane Andrew: broken toys, holes in walls, a crack from top to bottom in a full-length mirror on the bathroom door of the little house where I lived until just after my seventh birthday. My dad purposely didnt replace that mirror as a reminder, a monument to me. Subsequently, when hed see me heating up, hed point to it and ask one of those questions to which adults never really want an answer: Are you proud of that?

No, I lied, my bottom lip stuck out so far he could have pulled it over my forehead. Of course I was proud of it; Id had to slam it three times to get it to break.

There was a famous family story about how my temper had been cured right around the age of two. It was told by my mother at bridge club, Christmas get-togethers, and you-think- your -kids-are-a-pain-in-the-butt afternoon coffee sessions at the Chief Caf. It went something like this: Chris was very difficult to deal with, even at an early age. When things didnt go his way, he would throw himself into the air, kick his legs out from under him, and land hard on the floor. I was afraid hed hurt himself, so I called Dr. Patterson for advice. Dr. Patterson said, Just roll one of those wooden alphabet blocks under him when he goes up. That should take care of it. So the next time he launched himself, I rolled the block under him, and sure enough he never did it again.

I knew how to keep this story going; Id done it for years. But, Id say, pointing toward the sky.

But, my mother went on, then he began storming into the bathroom and hitting his head against the bathtub when he got mad.

So you called the ever-compassionate Dr. Patterson. I said.

And he told me to help him. Just push his head a little harder than he intended.

And lo and behold

He stopped hitting his head against the bathtub.

Id heard that story all my life, and had been convinced it was a good one, probably because it was about me. On the thousandth telling, however, I sat in a circle in my parents living room with a group of their friends on Christmas Eve. I was in my mid-thirties, and a thought that should have crossed my mind eons ago pried its way into my consciousness. I said, Jewellthe Crutcher kids always called our parents by their first names, which probably deserves closer scrutiny somewhere in this confessionaldo you remember the long crack in the full-length mirror in the bathroom at the little house?

She frowned. Of course. Your father wouldnt get it fixed. He left it as a reminder to you.

Of my temper, I said. I did that when I was five. Do you remember the hole I kicked in the plasterboard in my bedroom when Paula Whitson asked Frankie Bilbao instead of me to the Sadie Hawkins dance?

Jewell released a long sigh. Your father didnt have that fixed, either.

As a reminder of my temper, I said. I did that when I was a junior in high school. Do you remember the Volkswagen Bug I had up until about six months ago? With the top that looked as if it had been stung by bees from my punching it from the inside when the electrical system died on a busy street?

Yes, dear.

Crutch wouldnt have had that fixed, either, I said, smiling at my dad. I did that when I was thirty-three, a little over a year ago. Your story isnt about curing a kids temper. Its about pissing him off for the rest of his life by rolling blocks under him and whacking his head against the bathtub instead of letting him have his two-year-old rage. Stop telling it.

What my mother didnt say thenand something she and I often talked about years later in the long-term care wing of Valley County Hospital where she had gone to die slowly of emphysema resulting from forty years of a two-and-a-half-pack-a-day habitwas that her fear for me in those days wasnt really that Id hurt myself bouncing off the floor or banging my head, but that I would grow up with the same temper that stalked and embarrassed and humbled her throughout her own life. Though I couldnt have known it in those early years, it was one of my first experiences with a phenomenon I discovered years later as a child abuse and neglect therapist at the Spokane (Washington) Mental Health Center: Shit rolls downhill.

Im sure I could audit my early life and find times when my temper was my friend, when it got me through situations where my fear stopped me cold. It certainly helped me survive my early years on the Cascade High School football team where I started out as a 123-pound offensive lineman, when in practice Id get so angry at the grass stains on my back and the cleat marks on my chest that Id finally hit someone hard enough to satisfy the coach sufficiently to let me out of the drill. And it got me through my one and only full-tilt fight in junior high school when my embarrassment turned to rage the moment I saw the aforementioned Paula Whitson witness Mike Alkyre cracking my jaw. It took three guys to pull me off, and though I was still the odds-on kid most likely to have my butt kicked by someone from a lower grade, some of them would think twice after watching me cross over into the land of I Dont Care. But far more often than not, my temper brought out behavior that made me embarrassed to show my face around our lumber town of fewer than a thousand citizens for a couple of weeks.

Case in point. The biggest, best holiday (with the possible exception of Christmas) in Cascade, Idaho, during my childhood years had to be the Fourth of July. A parade led by the towns most prominent horsemen, followed by floats sponsored by virtually every town business, followed by preschoolers on crepe-paper-laden tricycles dodging piles of horseshit that rose to their knees, brought out nearly every ambulatory citizen. The Junior Chamber of Commerce sold hamburgers and pronto pups and cotton candy and ice cream and minor fireworks from plywood stands built on every other street corner. Wed watch or participate in the parade, eat ourselves sick through the lunch hour, then gather at the high-school track, a potholed, quarter-mile dirt road circling the football field, and surrounded by a larger, five-eighths-mile horse-racing track even more potholed, where we would participate in foot and bicycle races before settling into the stands to watch the kids and adults from farms and ranches around town, and up from the flat-lands outside Boise and Caldwell, race their horses.