2012 Random House Trade Paperbacks Edition

Copyright 1983 by John Updike

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House Trade Paperbacks, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE T RADE P APERBACKS and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, in 1983.

Owing to limitations of space, all permissions to reprint previously published material may be found on .

eISBN: 978-0-679-64584-9

www.atrandom.com

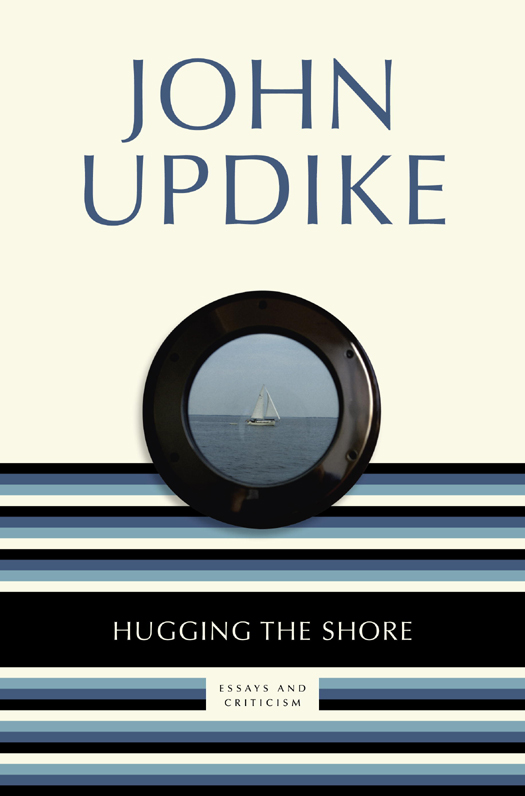

Cover design: Gabrielle Bordwin

Cover photograph: Stephen St. John/Getty Images

v3.1_r1

Foreword

W RITING CRITICISM is to writing fiction and poetry as hugging the shore is to sailing in the open sea. At sea, we have that beautiful blankness all around, a cold bright wind, and the occasional thrill of a gleaming dolphin-back or the synchronized leap of silverfish; hugging the shore, one can always come about and draw even closer to the land with another nine-point quotation. This is a big book but perhaps a quarter of the words belongs to other people. A good review is, among other things, a little anthology; my own experience of authorship urges me to heed the authors exact expressions and to condemn him, if he must be condemned, out of his own mouth. One of the chief labors, strange to say, of this assembling has been to ascertain which paragraph indentations, in the excerpted passages, really are part of the text: The New Yorker, where most of these reviews appeared, mechanically indents every such excerpt in smaller type, so I had to look up all the originals again. Also, for reasons known only to the fabled ur-fathers of its style manual, all titles are set in quotes instead ofmy orthodox preferenceitalics. But for such fine points, I have changed little, and have nothing to complain of in the handsome way this most scrupulous and considerate of magazines has sponsored my improvised sub-career as a book reviewer. Edith Oliver calls me up to suggest books or to approve my suggestions; Susan Moritz patiently escorts the untidy manuscript into smooth, error-free type. Under the wings of their recurrent kindness and acumen and coddling good humor the bulk of this book was produced, and it is gratefully dedicated to them.

As with this collections predecessor volumes, Assorted Prose and Picked-Up Pieces, I have included a number of oddmentsbrief essays turned to oblige a friend, attempts at humor and fantasy, journalistic assignments. The oldest piece in the Persons and Places section is A Mild Complaint, which was blithely composed in January of 1961, accepted promptly by The New Yorker, and then allowed to languish on the bank of unpublished casuals as the years and the decades lumbered by. I assumed that the piece, so fragile and literary in its joke, was thus informally killed; but when I suggested that I be allowed to give it decent burial in this omnibus the editors pronounced the little thing still vital despite its long coma and ran it in the issue of April 19, 1982twenty-one years, three months, and a day after the date of its composition. The second-oldest piece is The Tarbox Police, originally published in the March 1972 issue of Esquire and waiting since then for the kindred company of other insufficiently famous Americans to bring Cal, Hal, Sam, and Dan into hardcovers. The ten imaginary interviews were published separately as an elegant slim brown volume by the Lord John Press under the tide People One Knows, a title I have omitted but echoed here in the last section, which immodestly marshals some autobibliographical prefaces and responses but at least has the good taste to exclude all of those spoken interviews pulled from a limp-witted and complaisant author, whirled onto cassette tape, and then elevated, with many a typists flub, to the dignity of graven utterance. Let them perish in the pit of media-inspired ephemera! Every word in this book has been written.

I have tried to group the reviews into bundles handy for piecemeal reading. Since it is my habit, by way of giving good measure, to review several books together, some violence has been done to achieve these new groupings: for the sake of national cohesion, Muriel Spark had to be disentangled from both Ann Beattie and Raymond Queneau, and Queneau from D. M. Thomas. But in general, since the pairing of books often gives the review its coda, and yields chords that could not be struck otherwise, I have striven to keep the reviews as they originally were, at the cost of some disorder. Italo Calvino and Stanislaw Lem appear in two different sections, for instance, and my running appreciation of Anne Tyler is interrupted by considerations of Ursula K. Le Guin and John Cheever. The general trend of arrangement is chronological, patriotic (America first), and from fiction to non-fiction. Not counting the classics pondered in Three Talks on American Masters, one hundred thirty-one of other peoples books34,869 pages, by my calculationare specifically reviewed or introduced, all within the eight years since I wrapped up Picked-Up Pieces with the prayer Let us hope, for the sakes of artistic purity and paper conservation, that ten years from now the pieces to be picked up will make a smaller heap.

The heap is not smaller, and the ten years are not even up. What is my excuse, and why do I feel obliged to offer one? How better would my eyes, wits, and fingertips have been employed than with those 34,869 pages? Would I really, instead, have read through the complete works of Dickens and Thackeray and taught myself Italian? Or would I have misspent the time in hardware stores, searching for the perfect doohickey to fit into my broken thingamabob? What is this shore I hug so repeatedly, with such a squint of guilt? Were not these exercises in appreciation and exposition composed, like anything else, by taking a deep breath, leaning out over the typewriter, and trying to dive a little deeper than the first words that come to mind? Of some I am proud enough, as work completed and self-education achieved. Of none am I ashamed, else I would not have admitted them to my summer-long clerical labor, my mustering of deteriorating tearsheets into the hefty form of this book. Another book. Another slain forest. Another pious claim on our besieged pocketbooks. Even in the age of Ecclesiastes (third century B.C. , according to most scholars), the need for more books seemed doubtful. Whereas book reviews perform a clear and desired social service: they excuse us from reading the books themselves. They give us literary sensations in concentrated form. They are gossip of a higher sort. They are as intense as television commercials and as jolly as candy bars. I myself usually turn to the book reviews in a magazine or a newspaper just after the cartoons or the sports section, and I want them to be well done. That must be why I began to do them myself, in 1960.