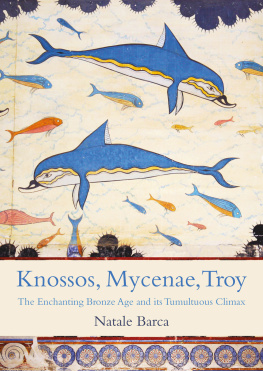

Knossos and the Prophets of Modernism

cathy gere

KNOSSOS & the prophets of modernism

the university of chicago press

Chicago & London

Cathy Gere is assistant professor in the history of science and medicine at the University of California, San Diego. She is the author of The Tomb of Agamemnon .

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2009 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2009

Printed in the United States of America

18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 1 2 3 4 5

isbn -13: 978-0-226-28953-3 (cloth)

isbn -10: 0-226-28953-2 (cloth)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gere, Cathy, 1964

Knossos and the prophets of modernism / Cathy Gere.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

isbn -13: 978-0-226-28953-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

isbn -10: 0-226-28953-2 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Palace of Knossos (Knossos). 2. Evans, Arthur, Sir, 18511941. 3. Arts20th centuryGreek influences. 4. Modernism (Aesthetics). 5. Archaeology and art. 6. ArchaeologyPolitical aspects. I. Title.

df 261. k55g 47 2009

939'.18dc22

2008053986

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

To the memory of my father

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My greatest intellectual debts were incurred in the History and Philosophy of Science Department at Cambridge University. Jim Secord untangled the more tortuous knots of my labyrinthine research with his characteristic combination of geniality and rigor. Nick Jardinea polymath whose profound grasp of the history of history of science gives his feedback the reassuring authority of the longer viewread drafts of every chapter and managed to deliver his criticisms in such a way that I came away encouraged. John Forrester provided unparalleled depths of insight into the history of psychoanalysis. On a couple of memorable occasions Simon Schaffer read drafts and summarized my argument, adding his own dazzling interpretations of the material under the guise of paraphrasing mine.

My thanks to the curators of the Arthur and John Evans archives at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, and the librarians at the Beinecke Library at Yale, for granting access to the manuscript sources I have used in this book. Archaeologist and historian of archaeology Nicoletta Momigliano reviewed a previous version of the manuscript for a publisher and provided many invaluable suggestions and essential corrections. Conversations with the participants in the conference that she subsequently organized on the history and politics of Minoan archaeology were inspiring and informative, especially those with Yannis Hamilakis, Kenneth Lapatin, David Roessel, Susan Sherratt, and the late Andrew Sherratt. Talking with John Tresch about the prophets of modernism has always sent me back to them refreshed and restored, and my thanks to him for providing such constructive feedback on parts of the manuscript. My editor Karen Darling has expertly shepherded this work to completion, and I count myself lucky to be among her first authors at the University of Chicago Press. This book was much improved by the criticisms and suggestions of three anonymous reviewers for the press.

On a more personal note, I thank my brother Charlie Gere for blazing the trail with such generosity, and my mother Charlotte Gere for all her supportmaterial, psychological, and intellectual. I am grateful to Anandi, Anjan, Jim, Krister and Pam for the gift of friendship during what could otherwise have been a lonely first draft. Finally, my thanks to my partner Hildie Kraus, for accompanying me to Psyches Cave, for having brilliant insights into reconstruction, for sending me ridiculous verses about H.D., for proof-reading an unconscionable number of different versions of this book, and, above all, for always wearing Zarathustras rose-chaplet crown of laughter.

INTRODUCTION

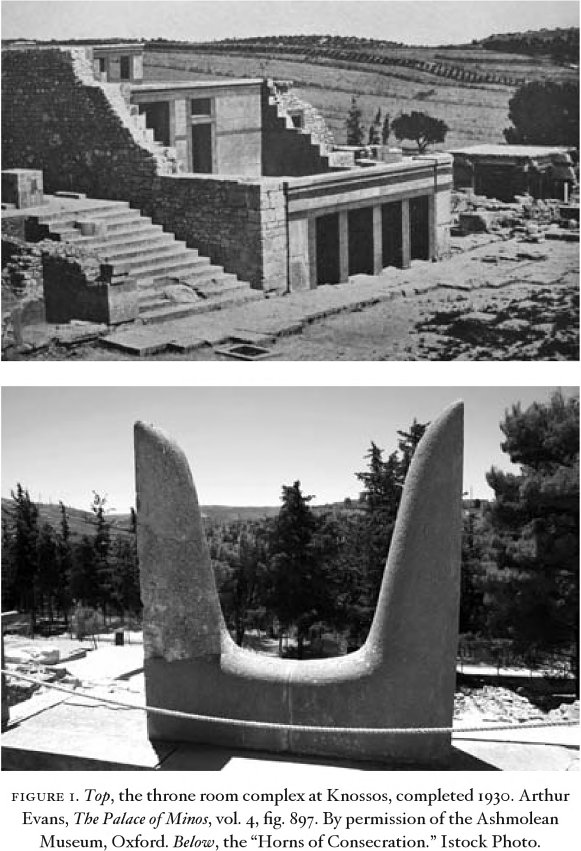

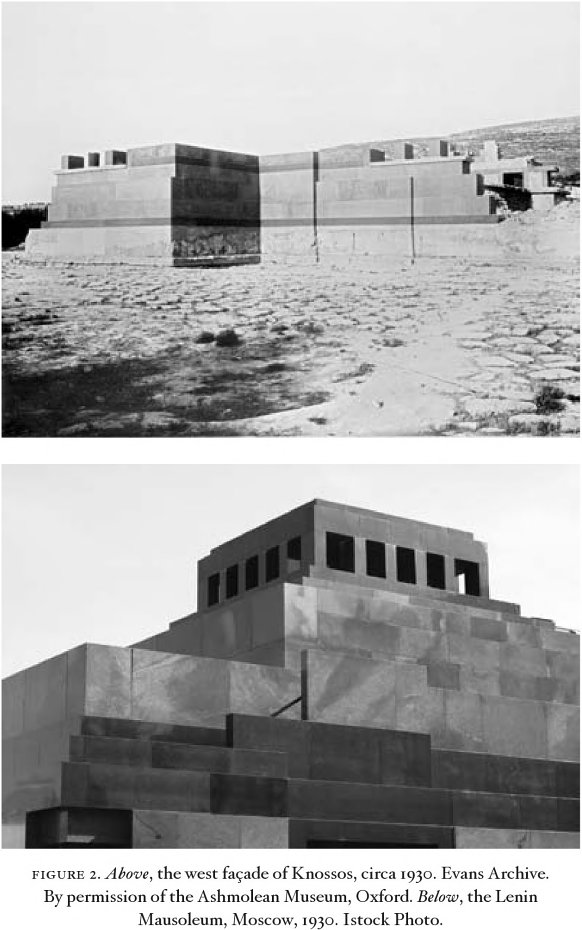

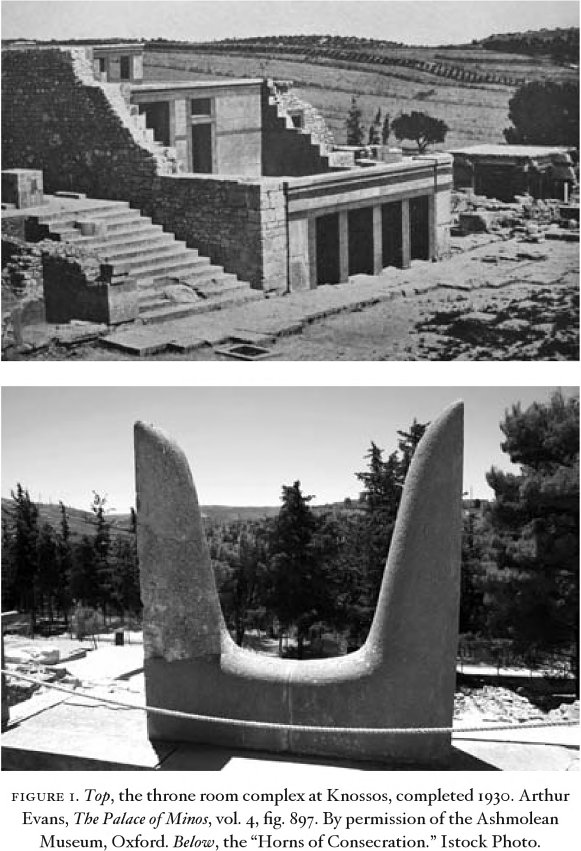

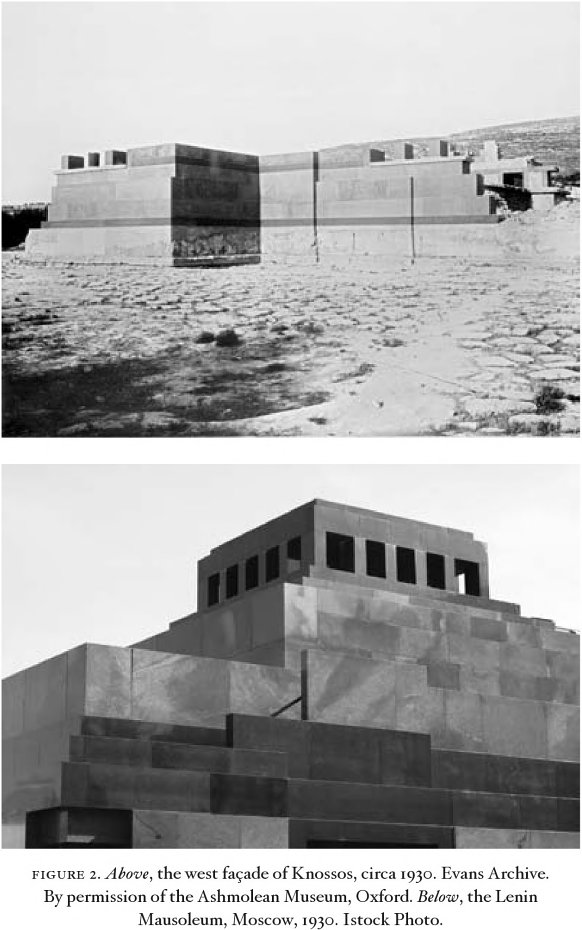

Cretes premier tourist attraction, the fabled Bronze Age Palace of Knossos, enjoys the dubious distinction of being one of the first reinforced concrete buildings ever erected on the island. Reconstructed by the English archaeologist Arthur Evans between 1905 and 1930, the walls of the palace are built of square concrete beams filled with lime-stone rubble masonry. Gray concrete floors, their edges molded in imitation of broken stone, are supported by squat, downward-tapering red pillars. Parts of Knossos are pure modernism: the throne room complex comprises three stories of unadorned square concrete pillars that rear up from the central court like a flimsy Le Corbusier exercise; a photograph of the west faade taken right after its completion in 930 looks eerily similar to Alexei Shchusevs Lenin Mausoleum in Moscow of the same date; the south flank of the palace is dominated by a subBarbara Hepworth sculpture known as the Horns of Consecration.

A little north of the palace stands the Villa Ariadne, a lavish colonial bungalow that Evans commissioned in 1905 to serve as his headquarters. Named for Evanss favorite character in Cretan mythology, the villa has a long garden wall running along the road that leads to Cretes capital city, Iraklion. Only a couple of undulating fields farther along, the postwar urban sprawl appears on the hills, threatening to engulf the palace and its environs and turn Knossos into a suburb. It will fit in well. Nearly eighty years after the completion of the concrete reconstructions and the rest of the country has caught up: today all of Greece is liberally studded with half-built, low-rise, skeletal modernist ruins, stairs climbing to nowhere, roofs bristling with rusting iron rebar.

Evans did not set out to reconstruct a Bronze Age palace using reinforced concrete. His excavation of the site began in the early spring of 1900. A few short weeks into the dig his workmen uncovered the oldest throne in Europe, a carved gypsum chair flanked by frescos. The chairits back plastered right into the wall behindcould not be moved off-site, and so the following season a bit of scaffolding was run up to support a protective shelter over it. Desiring a more artistic effect, Evans then substituted wood-and-plaster columns for the scaffolding, their downward-tapering shape and red color based on the painting of a building on a fresco fragment. As the dig went on, more squat red columns were constructed to prop up the crumbling walls of other parts of the building. In 1905, work began on the Villa Ariadne, and as soon as Evans saw how quickly its reinforced concrete shell went up, he realized that he had stumbled upon the most practical solution to the problem of protecting and supporting the remains of the ancient palace. Inspired by the plasticity, indestructibility, and relative cheapness of the material, he eventually undertook the wholesale and highly speculative reconstruction of large areas of the building. By the end of 1930, modernist Knossos was complete.

According to Evans, Knossos was the true Cretan Labyrinth, the historical reality behind the myth of the virgin-devouring Minotaur. The excavations, however, seemed to belie the bloodthirsty legends. The ogres den turns out to be a peaceful abode of priest-kings, in some respects more modern in its equipments than anything produced by Classical Greece,1 he announced in the introduction to his four-volume excavation report, The Palace of Minos. In this epic work, Evans bequeathed to his war-torn age a scientific vision of life before the FallMinoan society reconstructed as Western civilizations earliest blossoming, a gilded infancy suckled by a benevolent mother goddess, a time of peace and plenty on a beautiful island protected by the sea.

Next page