PRAISE FOR SPURIOUS

Its wonderful. Id recommend the book for its insults alone.

SAM JORDISON, THE GUARDIAN

Viciously funny.

SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE

Im still laughing, and its days later.

LOS ANGELES TIMES

A tiny marvel [A] wonderfully monstrous creation.

STEVEN POOLE, THE GUARDIAN

PRAISE FOR DOGMA

Uproarious.

THE NEW YORK TIMES

[Dogma] brings back W. and Lars, the most unlikely and absurd literary duo since Samuel Becketts Vladimir and Estragon Like Godot, this novel is a philosophical rumination, at once serious and playful, on the nature of existence and meaning. While its comic, there is at bottom a profoundly tragic sense of the chaos and emptiness of modern life. Despair has rarely been so entertaining.

LIBRARY JOURNAL

Just when my hilarity over the first book of their misadventures, Spurious, had faded to a low chuckle, Dogma comes along. Between the two books, theres almost no point in breathing, much less coming to any strong conclusions about life, the universe, and everything.

LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS

Witheringly, gut-bustingly funny.

THE NEW INQUIRY

The epithet Beckettian is perhaps the most overused in criticism, frequently employed as a proxy for less distinguished designations such as sparse or a bit depressing. But Lars Iyers fiction richly deserves this appellation. His playfully spareand wryly depressinglandscape, incorporating a bickering double act on a hopeless, existential journey, is steeped in the bathos, farce, wordplay and metaphysics of the man John Calder referred to as the last of the great stoics, its characters accelerating towards a condition of eternal silence, fuelled only by the necessity of speaking out.

THE TIMES LITERARY SUPPLEMENT

PRAISE FOR EXODUS

There is a superfluous joy to these novels They are satisfying paradoxesdifficult books which are consummately readable; exuberant books about bleakness.

THE SPECTATOR

The saddest, funniest undynamic duo since Vladimir and Estragon Like Spurious and Dogma, Exodus is a novel which depends almost entirely on the quality of its scorn. And on any scorn-rating it scores pretty highly.

THE GUARDIAN

Iyers books arent so much sad as brimming with good tidings about a utopia that remains pure as long as no one ever does anything Like Beckett, they use art to remind us that the whole point is to try, and fail, then try again, and fail better next time.

HAZLITT

The saddest, funniest undynamic duo since Vladimir and Estragon Like Spurious and Dogma, Exodus is a novel which depends almost entirely on the quality of its scorn. And on any scorn-rating it scores pretty highly.

THE GUARDIAN

With Exodus, as he did with Spurious and Dogma before it, Iyer has shown that a picaresque novel can be as good a vehicle for philosophy as any.

RAIN TAXI

It was more than a book: it was a revelation, in that Biblical sense of words being exposed down to their meaning, to the deed in the world to which they referred.

THE QUIETUS

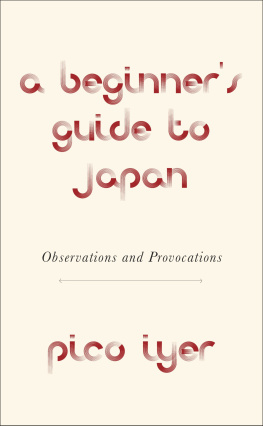

Also by Lars Iyer

NONFICTION

Blanchots Communism: Art, Philosophy and the Political

Blanchots Vigilance: Literature, Phenomenology and the Ethical

FICTION

Spurious

Dogma

Exodus

WITTGENSTEIN JR

Copyright 2014 by Lars Iyer

First Melville House printing: September 2014

Melville House Publishing

145 Plymouth Street

Brooklyn, NY 11201 | and | 8 Blackstock Mews

Islington

London N4 2BT |

mhpbooks.com facebook.com/mhpbooks @melvillehouse

ISBN: 978-1-61219-377-9 (ebook)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014945089

Design by Christopher King

v3.1

Contents

When you are philosophising you have to descend into primeval chaos and feel at home there.

Wittgenstein

1

Wittgensteins been teaching us for two weeks now.

Was it Edes idea to call him Wittgenstein? Or Doyles?

He doesnt look like Wittgenstein, its true. Hes tall, whereas the real Wittgenstein was small. Hes podgy, whereas the real Wittgenstein was thin. And if hes foreignEuropean in some sensehe has barely the trace of an accent.

But he has a Wittgensteinian aura, we agree. He is Wittgensteinisch, in some way.

He has clearly modelled himself on the real Wittgenstein, Doyle says (and Doyle knows about these things). He dresses like Wittgenstein, for one thingthe jacket, the open-necked shirt, the watch strap protruding from his pocket. And he behaves a bit like Wittgenstein too: his intensityhis lips are thinner than any weve seen; his impatiencethe way he glared at Scroggins for coming in late; his visible despair.

And of course, like the real Wittgenstein, he has come to Cambridge to do fundamental work in philosophical logic.

He sits on a wooden chair at the top of the room, bent forwards, elbows on his knees. His gaze is directed downwards. His eyebrows are raised, and his forehead is furrowed. He has the appearance of a man in prayer (Doyle). Of a constipated man (Mulberry).

He doesnt prepare his teaching. He doesnt lecture from notes. At most, he produces a scrap of paper from his pocket and reads out a phrase, or a sentence. He wants simply to think aloud about certain problems, he says.

Sometimes he writes a word or two on the blackboard on the mantelshelf. In the first week: Denken ist schwer (thought is hard). In the second: Everything is what it is, and not another thing. Today: I will teach you differences.

None of us understands the problems he is wrestling with, we agree. None of us can follow his methodwhat is he looking for?

Not all of us care, of course. Mulberry is drawing cocks in his notebook. Guthrie wears sunglasses over closed eyes. Benwell groans audibly when Wittgenstein asks him a question.

When will he actually say something? When will he present an actual argument?Mulberrys taking bets.

He proceeds from reflecting on one question to another. From one remark to another. But when will he answer his questions? And what do his remarks mean?

A hand in the air.

DOYLE (humbly): Im having trouble following the argument.

WITTGENSTEIN: Thats because Im not presenting an argument. I am posing questions, thats all.

DOYLE: I dont understand. I cant follow your class.

WITTGENSTEIN: I have no intention of making myself understood.

DOYLE (imploringly): I have no idea whats going on.

WITTGENSTEIN: That is to the good. At this stage, you should have no idea whats going on.

Silence in class.

DOYLE: Perhaps we arent bright enough to follow you.

WITTGENSTEIN: Intelligence is nothingyoure all clever. It is pride that is your obstacle. It is pride that is your enemy as students of philosophy. For pride leads you to believe that you are something you are not.

Wittgenstein surveys the room, looking carefully at us. He can see we know ourselves to be