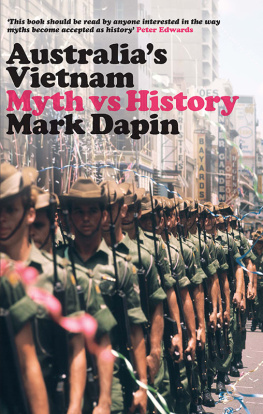

A portrait not just of warfare and warriors but of beleaguered patriotism and pride. The violence recalled in Bloods is chilling. On most of its pages hope prevails. Some of these men have witnessed the very worst that people can inflict on one another. Their experience finally transcends race; their dramatic monologues bear witness to humanity.

Time

Terrys oral history captures the very essence of war, at both its best and worst. Wallace Terry has done a great service for all Americans with Bloods. Future historians will find his case studies extremely useful, and they will be hard pressed to ignore the role of blacks, as too often has been the case in past wars.

The Washington Post Book World

Wallace Terry set out to write an oral history of American blacks who fought for their country in Vietnam, but he did better than that. He wrote a compelling portrait of Americans in combat, and used his words so that the readerblack or whiteknows the soldiers as men and Americans, their race overshadowed by the larger humanity Terry conveys. This is not light reading, but it is literature with the ring of truth that shows the reader worlds through the eyes of others. You cant ask much more from a book than that.

Associated Press

Bloods is a major contribution to the literature of this war. For the first time a book has detailed the inequities blacks faced at home and on the battlefield. Their war stories involve not only Vietnam, but Harlem, Watts, Washington D.C. and small-town America.

Atlanta Journal-Constitution

I wish Bloods were longer, and I hope it makes the start of a comprehensive oral and analytic history of blacks in Vietnam. They see their experiences as Americans, and as blacks who live in, but are sometimes at odds with, America. The results are sometimes stirring, sometimes appalling, but this three-tiered perspective heightens and shadows every tale.

The Village Voice

Wallace Terry was in Vietnam from 1967 through 1969. In this book he has backtracked, Studs Terkel-like, and found twenty black veterans of the Vietnam War and let them spill their guts. And they do; oh, how they do. The language is raw, naked, a brick through a window on a still night. At the height of tension a sweet story, a soft story, drops into view. The veterans talk about fighting two wars: Vietnam and racism. They talk about fighting alongside the Ku Klux Klan.

The Boston Globe

The good, bad and the ugly of that war in one finely edited work. Terry. uses oral histories to provide the most comprehensive vision of those who foughtand returnedthat has yet been produced. Almost any glowing adjectiveor group of adjectives, for that mattercan be used to describe Bloods.

Detroit Free Press

This is an invaluable addition to the expanding legion of histories about the Vietnam War. A graphically illuminating but disquieting collection of twenty personal accounts reflecting the black military experience in Vietnam Through their recollections of the war, we see Americas internal racial strife set against a major conflict.

Chicago Sun-Times

The soldiers descriptions of the wars ugliness and that of Americans fighting and dying were so dramatically explicit a reader could visualize himself shivering in the monsoon rain, stalking through muddy swamps, and witnessing comrades cut the ears off dead Vietcong rebels to wear on their dog chains. Bloods is an attention-keeper. It lets the reader relive the emotions and the turmoil of these men during the war and upon returning home. Bloods recovers once-lost pages of the Vietnam War that should never be forgotten again.

Nashville Banner

Although Bloods are what black soldiers called themselves in Vietnam, the title also suggests the racism, vileness and bloodletting they experienced in Americas most unpopular war. But more than just a black view of the Vietnam conflict, the book is an absolute condemnation of war. If your eyes dont mist during one of the chapters, your tear ducts dont work.

Los Angeles Times

2006 Presidio Press Mass Market Edition

Copyright 1984 by Wallace Terry

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Presidio Press, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. Originally published by Random House, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., in 1984.

P RESIDIO P RESS and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

This edition published by arrangement with Random House, Inc.

eISBN: 978-0-307-83358-7

www.presidiopress.com

v3.1

I have an intuitive feeling that the Negro servicemen have a better understanding than whites of what the war is about.

General William C. Westmoreland, U.S. Army, Saigon, 1967

The Bloods is us.

Gene Woodley, Former Combat Paratrooper, Baltimore, 1983

Contents

Introduction

In early 1967, while at the Washington bureau of Time magazine, I received a telephone call from Richard Clurman, then chief of correspondents. Clurman wanted me to fly to Saigon to help report a cover story on the role of the black soldier in the Vietnam War. Already the war was dividing the Nation deeply. In the black community, highly popular figures such as Martin Luther King, Jr., and Cassius Clay were speaking out against it.

I gladly accepted the assignment.

The attention President Lyndon Johnson was giving to the Great Society and civil rights progress, which I was covering at the time, was being eroded by his increasing preoccupation with the war. The war was destroying the bright promises for social and economic change in the black community. I was losing a great story on the home-front to a greater story on the battlefront.

At that moment the Armed Forces seemed to represent the most integrated institution in American society. For the first time blacks were fully integrated in combat and fruitfully employed in positions of leadership. The Pentagon was praising the gallant, hard-fighting black soldier, who was dying at a greater rate, proportionately, than American soldiers of other races. In the early years of the fighting, blacks made up 23 percent of the fatalities. In Vietnam, Uncle Sam was an equal opportunity employer. That, too, made Vietnam a compelling story.

And finally, Vietnam was, as I told my worried wife who was concerned about my safety, the war of my generation.

In May of 1967 I reported in Time that I found most black soldiers in Vietnam supported the war effort, because they believed America was guaranteeing the sovereignty of a democratically constituted government in South Vietnam and halting the spread of communism in Southeast Asia. President Johnson called me to the White House to hear that assessment first-hand; he was pleased by my briefing.

Later that year I returned to Vietnam for a two-year assignment that ended when I witnessed the withdrawal of the first American forces in 1969. Black combat fatalities had dropped to 14 percent, still proportionately higher than the 11 percent which blacks represented in the American population. But by that same year a new black soldier had appeared. The war had used up the professionals who found in military service fuller and fairer employment opportunities than blacks could find in civilian society, and who found in uniform a supreme test of their black manhood. Replacing the careerists were black draftees, many just steps removed from marching in the Civil Rights Movement or rioting in the rebellions that swept the urban ghettos from Harlem to Watts. All were filled with a new sense of black pride and purpose. They spoke loudest against the discrimination they encountered on the battlefield in decorations, promotion and duty assignments. They chose not to overlook the racial insults, cross-burnings and Confederate flags of their white comrades. They called for unity among black brothers on the battlefield to protest these indignities and provide mutual support. And they called themselves Bloods.