It took more than a century, but weve finally got the book we deserve about baseballs most infamous batting race. Thanks to Rick Huhn, it was worth the wait.

Rob Neyer, national baseball editor of the website Baseball Nation

With graceful writing and exhaustive research, Huhn gives life to one of baseballs great untold stories.

Jon Wertheim, senior writer for Sports Illustrated

This is the kind of baseball history we need more ofa book grounded in a great story, shaped by intelligent assessments of the evidence, committed to accuracy and truth-telling, and presented in vigorous prose.

Reed Browning, author of Cy Young: A Baseball Life

The Chalmers Race seamlessly weaves its compelling stories and is a deftly told saga of a game-changing and living controversy.

Gerald C. Wood, author of Smoky Joe Wood: The Biography of a Baseball Legend

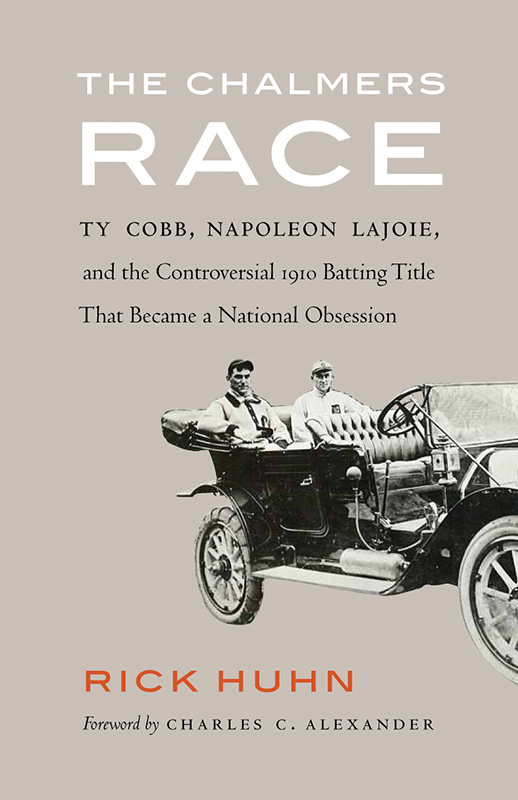

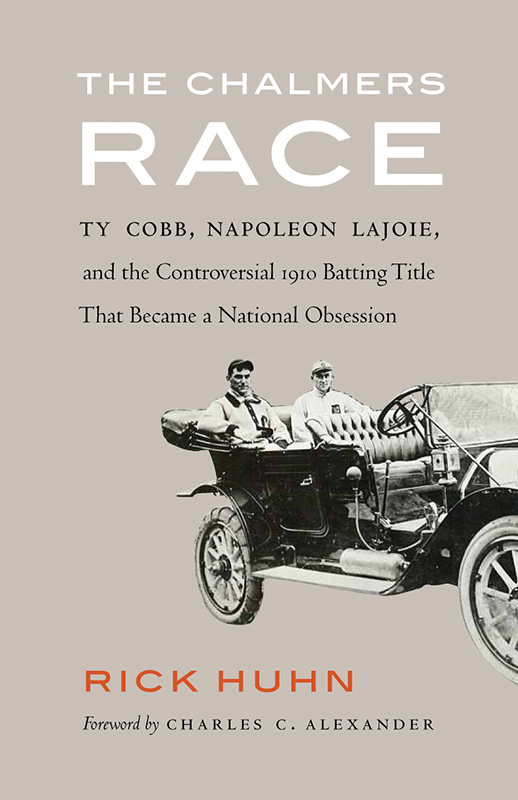

The Chalmers Race

The Chalmers Race

Ty Cobb, Napoleon Lajoie, and the Controversial 1910 Batting Title That Became a National Obsession

Rick Huhn

Foreword by Charles C. Alexander

University of Nebraska Press

Lincoln and London

2014 by Rick Huhn

Foreword 2014 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska

Cover image by Boris Chaliapin

Author photo courtesy of Rick Huhn

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Huhn, Rick, 1944

The Chalmers race: Ty Cobb, Napoleon Lajoie, and the controversial 1910 batting title that became a national obsession / Rick Huhn; foreword by Charles C. Alexander.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8032-7182-1 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8032-7376-4 (epub)

ISBN 978-0-8032-7377-1 (mobi)

ISBN 978-0-8032-7375-7 (pdf)

1. BaseballUnited StatesHistory20th century. 2. Batting (Baseball)United StatesHistory20th century. 3. Cobb, Ty, 18861961. 4. Lajoie, Napoleon, 18741959. I. Title.

GV 863. A 1 H 84 2014

796.357'6409041dc23

2013035015

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

To my wife, Marcia, who constantly provides spirit and meaning to my life

Hippodrome

Hippo*drome\, v. i. [imp. & p. p. -dromed; p. pr. & vb. n. -droming.]

(Sports) To arrange contests with predetermined winners. [Slang, U.S.]

Websters Revised Unabridged Dictionary, 1996, 1998 MICRA , Inc.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Foreword

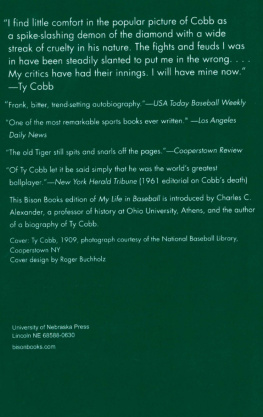

Charles C. Alexander

Most of todays baseball fans, especially younger ones, understand the 1919 World Series fixuniversally known as the Black Sox Scandalas the singular sin against the integrity of Americas oldest and most cherished team sport. Yet, as the growing number of people who have undertaken careful study of baseballs long history are aware, other questionable and often high-smelling episodes punctuate the sports pastfrom the bribes gamblers paid Louisville players to throw the 1879 National League pennant race (and their subsequent banishment) to recent and ongoing revelations of the use of steroids and other performance-enhancing drugs by players seeking an edge in strength and endurance. In short, dishonesty in its many forms has been a remarkably persistent feature of what was long hailed as the National Pastime.

Rick Huhns book is about what used to be called a hippodrome. Taken from the names of chariot race courses in ancient Greece and later of various circuses and theaters, hippodrome became a commonly used term in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century United States to denote athletic eventsusually baseball and prizefightingthat appeared not on the up-and-up, as fake rather than the real thing. Such was the case with the finale of the 1910 American League batting race between Detroits Ty Cobb and Clevelands Napoleon Lajoie. Both men were future Hall of Famers and outstanding performers in baseball history. What was at stake was not only the distinction of being the top man in batting average (then considered baseballs most significant offensive statistic), but winning the prize of a brand new Chalmers 30 touring car. That was the clever promotional scheme of Hugh Chalmers, a mostly forgotten pioneer in the emerging auto industry who offered a new 30 to the player with the highest average in the Major Leagues.

The competition for the Chalmers 30 brilliantly served Hugh Chalmerss purpose by creating mounting national interest in the batting races in the two leagues as well as in his motor cars (as the first generation of automobiles was called). Today, when many big-league players are multimillionaires, offering a new automobile as the prize for winning a batting title or any other achievement would seem of little consequence. But in 1910, when average family income in the United States was less than $1,000 per year, very few Americans had the wherewithal to purchase an automobile at even the $450 or $500 for which cheaper models were selling. The Chalmers 30, advertised for $1,500, was a hugely expensive item in the eyes of most people. Although the 30 wasnt Hugh Chalmerss top-of-the-line car (his 40 retailed for $2,750 and his limousine model for $3,000), it was an appealing prize, even for Cobb, who, like a growing number of professional ballplayers and other notables, had already acquired one or more early automobiles. (Each of which, with the exception of Henry Fords inaugural Model T in 1908, had the steering wheel located on the right side.)

By September 1910 Connie Macks Philadelphia Athletics were far ahead of everybody in the American League; Detroit, which had won three straight pennants (and lost each World Series) would finish a distant third, while Cleveland ended up fifth. Whatever suspense remained had to do with the race for the Chalmers 30, and it was obvious it would be decided in the American League between Cobb and Lajoie, whose averages remained in the upper .300s week after week. (The Philadelphia Phillies Sherwood Magee, who batted .331, led the National League.) As Rick Huhn reminds us, few players could have been more unlike in temperament and playing style. Ty Cobb, in his fifth year in the Majors but still only twenty-three, was a native Georgian, a lean, high-strung, fiery competitor who slapped and pushed the ball to all fields and ran bases with abandon. He was driving for his fourth consecutive batting championship. A fifteen-year Major Leaguer, Napoleon Lajoie (Larry to his baseball peers) turned thirty-five in September 1910. He was a native New Englander, usually easygoing, a big man for his time who was known as a hard hittera player who hit the ball as solidly and as far as anybody in the Majors. Having given up the burden of managing the Cleveland team, Lajoie was enjoying his best year since winning his third batting title in 1904.

Cobb had few friends on the teams he played for (and managed, 192126) during his twenty-four years in the big leagues, and his aggressive, hell-bent style aroused the ire of fans everywhere in the American League except Detroitand sometimes even there. Lajoie was generally well liked by teammates and by fans around the American League. In his home city, he was wildly popular, so popular that the Cleveland team was named in his honorthe Naps. Yet while Cobb often went out of his way to cultivate the favor of sportswriters and was usually a good interview, Lajoie, poorly educated and less articulate than Cobb, didnt like dealing with writers, nor were they fond of him.

At greater or lesser length, a number of people have written about the 1910 Cobb-Lajoie competition for the batting title and the Chalmers 30, including the present writer. But no one before Rick Huhn has examined so thoroughly the background, progress, and ins and outs of that American League season, which climaxed with the scandalous, season-ending doubleheader in Sportsmans Park in St. Louis between Cleveland and the local Browns. Unlike other scandalsthe 1879 Louisville mess; an attempt to bribe the umpires before the 1908 pennant-deciding New York GiantsChicago Cubs game; the effort by a Giants coach and player to bribe Philadelphias shortstop near the end of the 1924 season; and of course, most famously, the 1919 World Series fixwhat happened in 1910 involved neither money nor gamblers. It was more akin to the New York teams sloppy play in 1891 in losing five late-season games to the Boston National Leaguers, thereby helping Boston beat out Chicago for the pennant, and Minnesota outfielder Steve Bryes letting George Bretts fly ball drop safely in the last game of the 1976 season, which enabled Brett to edge Kansas City teammate Hal McRae for the American League batting title (a distasteful little episode that Huhn discusses toward the end of his book).

Next page