The Magic World

of Orson Welles

The Magic World

of Orson Welles

Centennial Anniversary Edition

JAMES NAREMORE

1978 by Oxford University Press, Inc.

1989, 2015 by James Naremore

Reprinted by arrangement with the author.

All rights reserved.

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Photo credits: RKO, Columbia Pictures, Wisconsin Center for

Film and Theater Research, Universal Pictures.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Naremore, James.

The magic world of Orson Welles / James Naremore.

Centennial anniversary edition.

pages cm

Includes filmography.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-252-03977-5 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-252-08131-6 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-252-09787-4 (e-book)

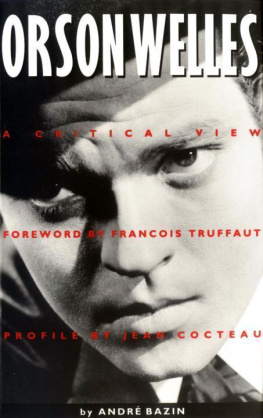

1. Welles, Orson, 19151985 Criticism and interpretation. I.

Title.

PN1998.3.w45N37 2015

791.4302'33092dc23 2015006093

[B]

For my son, Jay, as usual,

and in memory of Rosa Hart, my favorite director

Contents

Acknowledgments

My work on the first edition of this book, published in 1978, was supported by many institutions and individuals. The office of Research and Graduate Development at Indiana University provided me with a summer grant in 1976, and the National Endowment for the Humanities awarded me a summer fellowship the following year. In addition to these agencies, I was assisted by Charles Silver and the staff at the Museum of Modern Art, and by librarians at the New York Public Library, the Library of Congress, and the Wisconsin Center for Theater Research. Among the individuals, I must first of all thank film director Richard Wilson, an old friend of Welles, who answered my questions, allowed me to glance at the Mercury Theatre files, and gave me a memorable day in Hollywood. Ronald Gottesman, Robert Carringer, and Joseph McBride also helped with their knowledge about Welles. Claudia Gorbman and the late Charles Eckert, my colleagues at Indiana, read early parts of the manuscript and gave important criticisms. Joanne Eustis made a crucially important gift of her extensive library research on Welles, and Bill Kelly, Mark Kemmerle, Robert Ray, and Dennis Turner all read individual chapters and offered comments on the films.

The scope and shape of the book were influenced strongly by my editor at Oxford University Press, James Raimes, who also made a number of important incidental suggestions; for his faith in the project and for his intelligent, sympathetic ear, I owe him gratitude. I want also to thank Ellen Posner for her editorial assistance, and William Stott of the University of Texas, who recommended my work to Oxford at an early stage.

The book never would have been written at all without the enthusiasm of students in Comparative Literature C491 at Indiana, who inspired me and , in a different form, appeared in Literature/Film Quarterly and Focus on Orson Welles, and I am grateful to the editors, Thomas Erskine and Ronald Gottesman, for their encouragement.

For making the second edition of the book possible in 1989, I thank Suzanne Comer, Bill May, and the staff of Southern Methodist University Press. Special thanks to Martha Farlow for her handsome design, and to Elli Puffe and Kathy Lewis, who repaired my terrible spelling and helped to correct the multitude of mangled names and printing errors that had found their way into the original version. A few others also deserve mention: Jonathan Rosenbaum generously shared his ideas about Welles and helped me to see some of the late films. William G. Simon and the faculty of the Cinema Studies program at New York University honored me with an invitation to speak on Welles at a symposium they organized in May 1988; my talk on that occasion, subsequently published in the journal Persistence of Vision, provided the basis for the concluding chapter.

For this third edition, my thanks to Daniel Nasset and the staff of the University of Illinois Press. Special thanks to Jill Hughes for her expert copy-editing (who knew there was so much left to be done?), Tad Ringo for his supervision of production, and Lisa Connery for her design. And to Darlene Sadlier, who gave me her advice, support, and love.

INTRODUCTION

Orson Welles at 100

When the first edition of The Magic World of Orson Welles was published by Oxford University Press in 1978, I was a young college professor trained in literature and new to writing about film, without access to the trove of archival and biographical material on Welles that has since become available. Welles was alive and active, but when I wrote to him in the wild hope of seeing Don Quixote and some of his other unfinished work, he never replied. This was perhaps just as well. I was able to remain an independent observer, concentrating on the public record and aiming at a close study of the released films, most of which, in that pre-digital age, were available in 16mm prints.

When a second, revised edition of my book, containing a new concluding chapter, was published by Southern Methodist University Press in 1989, I noted in the preface the melancholy fact that it was now possible to begin a book about Welles in the same fashion as some of his films: with the death of the protagonist. Welles had died of a heart attack in Los Angeles in 1985, at the age of seventy. He was found with his typewriter in his lap, working until the very end. A day before, he had taped an appearance on Merv Griffins television show, where he performed a charming card trick and wryly described old age as a shipwreck. Although his health had not been good, he was quite busy. (An extended discussion of his crowded late years can be found in Joseph McBrides Whatever Happened to Orson Welles?) Jonathan Rosenbaum has estimated conservatively that during the first half of the 1980s alone, Welles was working on at least a dozen films or scripts for films, among them The Magic Show (documenting his magic act, without camera tricks); Don Quixote (begun in the 1950s); The Assassin (about Sirhan Sirhan); The Other Man (based on Graham Greenes The Honorary Consul); Dead Giveaway (based on Jim Thompsons A Hell of a Woman); The Dreamers (derived from two Isak Dinesen stories); King Lear (a sort of video closet drama to be shot mostly in black-and-white close-ups); and Mercedes (from a short story by his late-life partner, Oja Kodar).

This prodigious quantity of work was not unusual for Welles. Throughout his life he was involved in multiple activities and at times seemed to operate in a whirlwind. In the single year of 1940, for example, he produced, directed, acted in, and supervised scripts for a dozen radio dramas; appeared as a guest on a couple of other radio programs; oversaw the production of a recorded version of Macbeth by the Mercury players; toured thirteen cities with a lecture titled The New Actor; wrote a screenplay for Dolores del Rio; completed the screenplays for Smiler with a Knife and Mexican Melodrama (discussed in ); completed the screenplay and principal photography of Citizen Kane; sought Richard Wrights approval for the forthcoming Mercury stage production of

Next page

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.