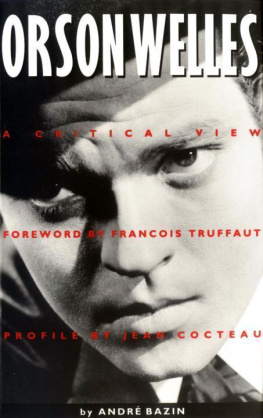

Andre Bazin - Orson Welles: A Critical View

Here you can read online Andre Bazin - Orson Welles: A Critical View full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1992, publisher: Acrobat Books, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

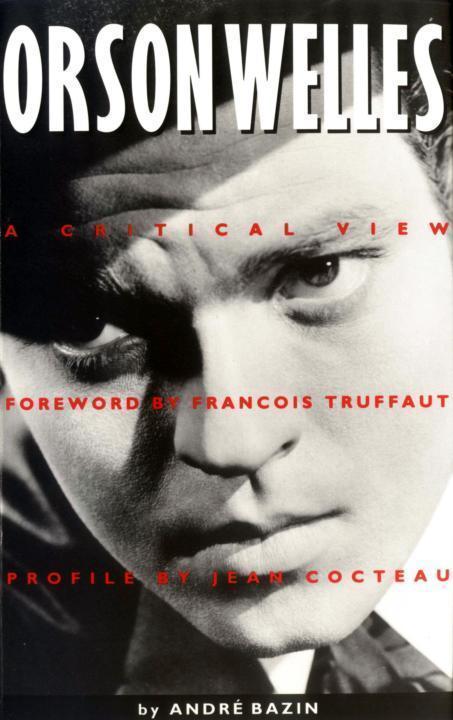

- Book:Orson Welles: A Critical View

- Author:

- Publisher:Acrobat Books

- Genre:

- Year:1992

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Orson Welles: A Critical View: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Orson Welles: A Critical View" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Orson Welles: A Critical View — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Orson Welles: A Critical View" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

FOREWARD BY FRANCrOIS TRUFFAUT

PROFILE BY JEAN COCTEAU

by Francois Truffaut

Andre Bazin was a young critic at the time of the Paris opening of Citizen Kane in July 1946. He was twenty-eight and had been a professional critic for two years. Along with Marcel Carne's Le four Se Live, Jean Renoir's La Rigle du Jeu and Charlie Chaplin's Monsieur Verdoux, Citizen Kane is undoubtedly the film that excited him the most.

Bazin's articles on Charlie Chaplin and Orson Welles made him the leader of the young postwar critics who wrote for L'Ecran Franfais as well as La Revue du Cinema, which expired after twenty issues and was reborn as Les Cahiers du Cinema.

Bazin's admiration for "the wonder kid from Kenosha," as magazines were already styling him, was to remain undiminished, for he devoted his first book, in 1950, to Welles, who had just shot Macbeth and was preparing Othello. This little volume, superbly prefaced by Jean Cocteau, quickly went out of print and became a collector's item; and in 1958, shortly before his death, sparked by enthusiasm for Touch of Evil, Bazin prepared a revised and expanded edition, published here in Jonathan Rosenbaum's translation.

Over Christmas 1973, one of the gifts that the people of Hollywood delighted in giving was a framed version of a "Peanuts" cartoon by Schulz, published in the Los Angeles Times. This is what the seven drawings showed:

1. Linus turns on a television.

2. Lucy, his big sister, arrives and asks him: "What are you watching?"

3. Linus: "Citizen Kane. "

4. Lucy: "I've seen it about ten times."

5. Linus: "This is the first time I've ever seen it...."

6. Leaving the room, Lucy blurts out: " `Rosebud' was his sled!"

7. Linus writhes in agony: "Aaugh!"

This "Peanuts" strip demonstrates, if any demonstration is needed, the cinematic and extracinematic position that Citizen Kane has assumed in the cultural life of two generations. Just as the silent cinema was modified and stimulated by Griffith's The Birth of a Nation, Stroheim's Foolish Wives, and Chaplin's three-reelers, everything that matters in cinema since 1940 has been influenced by Citizen Kane and Jean Renoir's La Regle du feu.

In his first films, Charlie Chaplin played the character of the poorest and most humble man in the world. Simply in order to eat, he was compelled to steal food from a baby or a dog. Within a few years the success of Chaplin's films made him the most celebrated figure in the world, and naturally this gradually led him to abandon the character of the little tramp. Beginning with The Great Dictator, Chaplin assumed his celebrity completely; after having envisaged playing Christ, then Napoleon, he took on Adolf Hitler, who, Andre Bazin noted, "had dared to steal Charlie's mustache." Succeeding Hinkel-Hitler came Verdoux-Landru, the most famous lady-killer in the twentieth century (the germ of this film was supplied to Chaplin by Orson Welles), A King in New York (Chaplin versus McCarthy's America), and finally the diplomat Ogden Mears of The Countess from Hong Kong, a film whose autobiographical aspect has escaped many critics, who haven't read the accounts of Chaplin's trips around the world and who didn't think it necessary to make a mental substitution of Chaplin himself for Marlon Brando while watching the film.

Like Chaplin's, Orson Welles' work is autobiographical in a subterranean manner, and it also pivots around the major theme of artistic creation, the search for identity.

The great difference between these two men-and therefore between their works-is that Orson Welles has never known destitution, and further, that his celebrity preceded his entry into cinema, mainly because of the repercussions of the Mercury Theatre on the Air broadcast of October 30, 1938, devoted to the adaptation of H. G. Wells' The War of the Worlds. Accounts of this radio event and the panic that ensued have been given countless times and I won't linger over it, except to note that Orson Welles' position just before shooting Citizen Kane was unusual and paradoxical: instead of having to make himself known and recognized, Welles, who was then only twenty-five, found himself in the reverse position of having to uphold a reputation that was already immense. For all sorts of reasons that are easy to imagine, Orson Welles, working in New York in theatre and radio, was more celebrated than popular across America; his exploits aroused more curiosity than sympathy. From the time of his arrival in California, the world of Hollywood fostered a basic hostility toward him, which, over the years, has never changed. So Welles in 1939 must have felt that it was necessary to offer the public not only a good film but the film, one that would summarize forty years of cinema while taking the opposite course to everything that had been done, a film that would be at once a balance sheet and a platform, a declaration of war on traditional cinema and a declaration of love for the medium.

Andre Bazin was correct to state that "Citizen Kane and Ambersons could finally be a matter of childhood tragedy." For that is indeed the case, and certainly it is clear that the emotions Welles experienced in his youth molded the plot of Citizen Kane, even if, as Pauline Kael asserts, its theme and central character had been furnished by the co-scriptwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz (who would himself be more or less represented in the film by the character of the dramatic critic, Kane's college friend Jedediah Leland, played by Joseph Cotten).

Orson Welles is at his best when he tells stories about families: The Hollywood cinema of the period, sentimental and boy-scoutish, wasn't stingy in this respect, but Orson's familial vision scarcely resembles Louis B. Mayer's. In Welles' work, fathers, sons, uncles and aunts are of the possessive sort and the principal characters nearly always suffer from emotional traumas. Before Welles, this terrain of the confusions of adolescence had hardly been explored by Hollywood films, whose two favorite dialogue expressions seemed to be "You're a good boy, sonny" and "Daddy, you're the best pop in the world."

Orson Welles would never become an entirely American filmmaker for the good reason that he wasn't an entirely American child. Like Henry James, he would benefit from a cosmopolitan culture and would pay for this privilege with the disadvantage of not being able to feel at home anywhere; an American in Europe, a European in America, he will always be, if not a man torn, at least a man divided.

As an adolescent, with his father or his mother, Orson Welles visited Europe, China and Jamaica. His mother died during one of these trips, when Orson was eight, the age of the young Charles Foster Kane when he is forcibly separated from his mother: "Isn't it with the sled, whose perhaps unconscious memory will haunt him until his death, that he violently strikes, at the very outset of his life, the banker who has come to tear him from his play in the snow and his mother's protection, come to snatch him from his childhood to make him into Kane the citizen?" (Andre Bazin)

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Orson Welles: A Critical View»

Look at similar books to Orson Welles: A Critical View. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Orson Welles: A Critical View and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.