Table of Contents

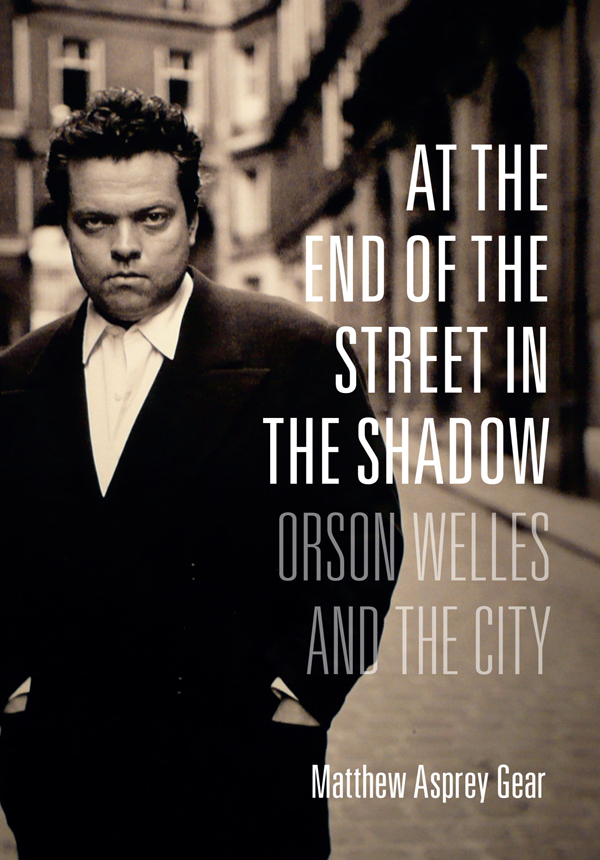

AT THE END OF THE STREET IN THE SHADOW

AT THE END OF THE STREET IN THE SHADOW

ORSON WELLES AND THE CITY

Matthew Asprey Gear

A Wallflower Press Book

Wallflower Press is an imprint of

Columbia University Press

publishers since 1893

New York

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2016 Matthew Asprey Gear

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-85090-2

Wallflower Press is a registered trademark of Columbia University Press

A complete CIP record is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-0-231-17340-7 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-17341-4 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-85090-2 (e-book)

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover image: Orson Welles photographed in Paris in 1952, by Fred Brommet

This book is for my mother

Contents

I am grateful to the Orson Welles scholars who generously shared their time and ideas with me during the research for and writing of this book: James Naremore, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Stefan Drssler, Josh Karp, and Scott Simmon. I also want to thank Kate Hutchens at the Special Collections Library at the University of Michigan and David Frasier at the Lilly Library at Indiana University for their hospitality and help during my research visits in January and February 2014, respectively. This book builds on the Touch of Evil chapter of my PhD thesis, completed at Macquarie University, Sydney, in 2011. Further funding from the university allowed me to make a research trip to the Filmmuseum Mnchen and present a preliminary version of the chapter on Mr. Arkadin at the Screen conference at the University of Glasgow in the summer of 2013. I also want to thank Peter Doyle, Noel King, Theodore Ell, Yoram Allon at Wallflower Press, Gary Morris at Bright Lights Film Journal, Ray Kelly at wellesnet.com, Luc Sante, Will Straw, Adrian Martin, Clive Sinclair, the late Lester Goran, Kathryn Millard, Mark Evans, Nicole Anderson, Ivn Zatz, and from the early days Bill Wrobel and Adriano.

Many thanks to Soledad Rusoci for her support throughout the writing of this book. Thanks also to Julie Asprey, Luke Asprey, Clare Anderson, Jace Davies, Amanda Layton, Ben Packham for his early insights into Citizen Kane, and in Buenos Aires Sabrina Daz Bialos, Ignacio Bosero, Arthur Chaslot, Valeria Meiller, and Nuestra Seora de los Candados.

Matthew Asprey Gear

Biblioteca Nacional de Maestros, Buenos Aires

September 2015

We could begin almost anywhere. He seems to have visited all the cities so precociously early that every return was tinged with saudade that untranslatable Portuguese word signifying nostalgic longing and the sweet sadness of loss. In fact, he picked up the word in Rio de Janeiro during what he later remembered as the last great carnival in that greatest of carnival cities.

So lets begin in Vienna, close to the Cold War border but also the former heart of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, one of several politically obsolete cultures Welles gently lamented during his forty-five years in cinema. In New Wien, a short travel segment he made for television in the late 1960s, our corpulent guide puffs a cigar and trails a billowing lodenmantel purely utilitarian, he insists through the wintry solitude of the city. Welles peers through the front window of Demel, the greatest of all the great Viennese pastry shops, and remembers how when the world was young I used to run riot in there. How sweet it was. The grand opulence of Welless hotel suite is merely de rigueur here at the Hotel Sacher thats the way it is. He wonders how much pink champagne must have been poured here into how many pretty ladies slippers, and remarks that late at night one can still seem to hear again the clop clop of the horse-drawn Fiakers bringing the old playboys back. He remembers from his own childhood days the formidable Frau Sacher herself.

He also recalled a particularly boring lunch in 1920s Bavaria seated beside Adolf Hitler. However accurate these unverifiable memories, Welless absurdly interesting early life was an education in history, culture, and the panoply of human types.

His 1969 homage to his fantasy Vienna an invitation to warm in the afterglow of faded glories is hardly a radical, interrogative film essay on this citys dynamic culture and history. Instead, Welles explains:

Your true Vienna lover lives on borrowed memories. With a bittersweet pang of nostalgia he remembers things he never knew, delights that only happened in his dreams. The Vienna that is is as nice a town as there is. But the Vienna that never was is the grandest city ever.

The mode of nostalgic reverie was hardly reserved for Vienna. It was, in fact, Welless characteristic approach to the past. His explanation to Peter Bogdanovich around the same time has been frequently quoted:

Even if the good old days never existed, the fact that we can conceive of such a world is, in fact, an affirmation of the human spirit. That the imagination of man is capable of creating the myth of a more open, more generous time is not a sign of our folly. Every country has its Merrie England, a season of innocence, a dew-bright morning of the world. Shakespeare sings of that lost Maytime in many of his plays, and Falstaff that pot-ridden old rogue is its perfect embodiment.

Its also characteristic that this Vienna segment, and the television special of which it was to be a part, Orsons Bag (aka One-Man Band), was never broadcast. And although he certainly appeared in front of the Riesenrad Ferris wheel hed immortalised by his role in Carol Reeds The Third Man (1949), Welles made only part of the segment on location in Vienna itself. He shot other parts in Zagreb, another former Austro-Hungarian city but by then a northern outpost in Josip Broz Titos Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Other parts were filmed in Los Angeles.

It was typical of Welless happy embrace of fakery to shoot parts of a documentary purportedly about Vienna in other cities. In this period he worked independently across Europe by what has been called patchwork. Alternating between multiple projects over long periods in different places, Welles funded stages of production via the film and television industries of various countries, when necessary with his acting income, or else by siphoning the resources of other directors projects through special arrangement or by subterfuge. No other major filmmaker of the time worked in this way, and certainly none with Welless ambition. Disenchanted with Hollywood, he invented both the methods and aesthetic forms of an independent personal cinema.