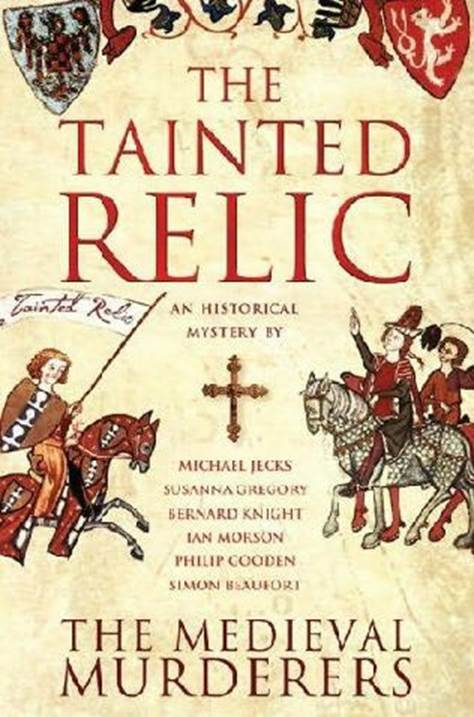

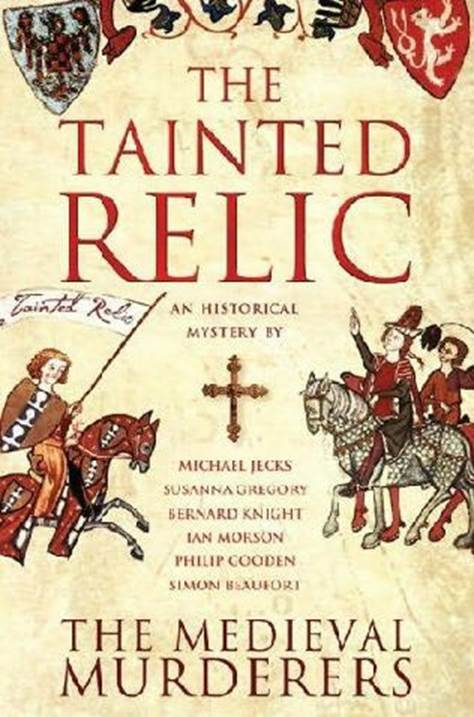

The Medieval Murderers

The Tainted Relic

The first book in the Medieval Murderers series, 2005

Prologue -

In which Simon Beaufort records dire events in Jerusalem in the 1100th year of Our Lord.

Act One

In which Bernard Knight relates dark deeds in Exeter during the reign of Richard Coeur-de-Lion.

Act Two

In which Ian Morson offers a labyrinthine tale of Oxford in the thirteenth century.

Act Three

In which Michael Jecks spins a web of intrigue in the county of Devon in the year 1323.

Act Four

In which Susanna Gregory recounts strange events in Cambridge in the middle of the fourteenth century.

Act Five

In which Philip Gooden takes the stage in London at the time of Will Shakespeare.

Epilogue -

In which Bernard Knight comes up to modern times.

Jerusalem, July 1100

Jerusalem had fallen to the Crusader armies, and the Holy City was in Christian hands at last. Already, even though only two days had passed since the infidel had been defeated, messengers were riding hard northward to take the momentous news to the Pope and the western kings, proclaiming to the world that God had delivered a great victory into the deserving hands of the invincible, glorious soldiers of His holy war.

Sir Geoffrey Mappestone, one of few English knights to join the Crusade, did not feel much like a conquering hero. Months of starvation, disease, foul weather and hardship had sapped his enthusiasm for the venture. When the towering walls of the Holy City had finally been breached, and the gates flung open to admit the rest of the army, the Christians had slaughtered their way through the civilian inhabitants like avenging angels, and Geoffrey had been sickened by it. The killing had continued for an afternoon, and then a night, so that when the first rays of sunlight lit Jerusalem from the east, it was to illuminate a vision from Hell.

No quarter had been given to any Muslim or Jew, so that the corpses of small children and old women lay next to those of able-bodied warriors. They had been massacred in their houses, doors and windows smashed by men frenzied by the stench of blood and the thought of plunder; they had been cut down in the streets when they had tried to run to safety; and, worst of all as far as Geoffrey was concerned, they had been murdered in their mosques and synagogues, where they had believed they would be spared.

Geoffreys liege lord, Prince Tancred, had seized the land surrounding the mighty Dome of the Rock, and had placed his banner over the Temple, promising those inside that they would be spared-in exchange for a handsome ransom, naturally. But the Crusader leaders despised each other as much as they did their enemies, and Tancreds promise of clemency was ignored by his rivals. When Geoffrey visited the Temple the following day, he was forced to wade through piles of corpses that reached his knees. The Jews in their chief synagogue fared no better. They were accused of helping the Mohammedans, and the building was set alight, burning to death all inside.

When there were no citizens left, and when every house, animal, pot and pan had been seized and divided among the invaders, the sacking came to an end. The princes led their proud, blood-soaked warriors in solemn reverence to give proper and formal thanks to God in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Geoffrey did not join them, and instead went to stand on the city walls near the Dome of the Rock, wanting no part of the pious gloating that was taking place among the victors.

With the Crusaders at their devotions, and most of the population dead, the city was quiet. A goat bleated from a nearby garden, and a light, hot wind whispered from the desert and caressed the ancient walls. Eddies of dust stirred in the abandoned courtyard, and patches of dry-yellow grass trembled here and there. Geoffrey went to the battlements and looked out across the barren hillside, to where the Crusaders had camped before their final assault. Empty tents snapped and fluttered, and the odd retainer could be seen here and there, left behind to guard his masters treasure. Behind him, smoke rose in a greasy grey pall; the looters fires still smouldered among the ruins.

Geoffrey rested his arms on the wall and closed his eyes. The sun beat down on his bare head, and he felt sweat begin to course down his back. Some knights had dispensed with the mail and thick surcoats that had protected them during the battle, but Geoffrey felt uneasy in this alien city, with its minarets and pinnacles, confused jumble of alleyways and lanes, and cramped houses. His armour stayed where it was, and would do so until he felt safe.

What happened here will live in infamy for many centuries to come, came a quiet voice at his elbow.

Geoffrey spun around in alarm. His sword was out of his belt and he had it pointed at the throat of the man who had spoken almost before he had finished turning.

The man who stood next to him made a moue of annoyance, and pushed the weapon away. He was old, with a mouth all but devoid of teeth, and the deep wrinkles in his leathery skin suggested he had spent most of his long life under the scorching Holy Land sun. His clothes comprised a shabby monastic habit, worn leather sandals, and a waistband made from the braided sinews of some animal. His eyes were not the faded, watery blue Geoffrey usually associated with the very ancient, but were bright and clear, so that they looked as though they belonged in a younger, less feeble body.

You should be more careful, said Geoffrey irritably, glancing around to ensure the fellow was alone before sheathing his sword. It is unwise to slip up behind soldiers so softly-especially now.

Especially now, echoed the old man, regarding Geoffrey sombrely. You mean because your friends are so engorged by bloodlust that they strike first and only later demand to know whether we are friend or foe?

Yes, replied Geoffrey, turning away from him and leaning on the wall again. You should stay at home and wait for some semblance of order to be established. Until then, Jerusalem is a dangerous city for anyone without a sword-even for monks.

I have important matters to attend to, stated the old man indignantly. I cannot linger indoors, when I have so little time left. But you can help me.

I can, can I? said Geoffrey, amused by the presumption.

The old man looked across the courtyard to where the massive octagonal structure dominated Temple Mount, with its smooth, gleaming dome and its walls of brightly coloured tiles. Inside was a stone where, according to tradition, Abraham had prepared to sacrifice Isaac, and where the Jews believed the First Temples Holy of Holies had been located. Muslims thought it was the spot from where Mohammed had ascended on his Night Journey, and Geoffrey supposed it would now become a Christian shrine. Red-brown smears on the ground and an ominous splattering on the pillars still bore witness to where those under Tancreds protection had been murdered just two days before.

You did not like what happened here, Geoffrey Mappestone. You did not take part in it.

Geoffrey regarded him warily. How do you know my name?

The old man shrugged. I watched what happened, and I heard you arguing with the murderers who came to spill Mohammedan blood. I asked Sir Roger of Durham who you were, and he told me.

Are you Mohammedan? asked Geoffrey, thinking that if he were, then he would indeed be wise to remain hidden until the killing frenzy was properly over. His friend Roger was a good man, but even he had joined in the wave of violence.

Next page