The Medieval Murderers

The Deadliest Sin

The tenth book in the Medieval Murderers series, 2014

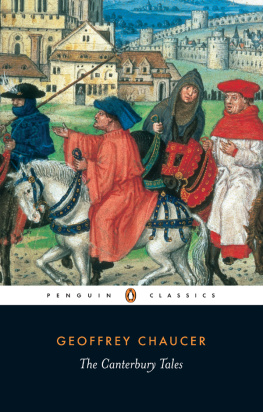

The Prologue, in which the pilgrims arrive at the Angel Inn

The first sin:

Michael Jecks tells a tale of Lust

The second sin:

Ian Morson tells a tale of Greed

The third sin:

Ian Morson tells a tale of Gluttony

The fourth sin:

Susannah Gregory and Simon Beaufort tell a tale of Sloth

The fifth sin:

Philip Gooden tells a tale of Anger

The sixth sin:

Bernard Knight tells a tale of Envy

The seventh sin:

Karen Maitland tells a tale of Pride

The Epilogue, in which the pilgrims depart from the Angel Inn

In fond memory of Dot Lumley (1949-2013), general agent and first editor for all theMedieval Murdererbooks.

Thanks for keeping us all in line.

The English say that April is the best month to make a pilgrimage. Once winter is over, the roads and tracks become passable again. The skies lift and the days draw out. People begin to grow restless.

But this particular spring, in the year of Our Lord 1348, was different from other springs. True, the days were growing lighter and longer as they always do, yet the people of England were not so much restless as terrified.

For a time at the end of the previous year it had been possible to ignore the rumours as mere invention, stories created to frighten children. Extraordinary tales were coming out of the east, tales of poisonous clouds that overwhelmed whole cities and even countries, with scarcely a human being left alive to tell the horrors he had witnessed. But because there were often reports of fantastical things out of the east it was not so hard to dismiss these new alarms.

Then the accounts of mass dying began to arrive from nearer at hand. The cloud of pestilence reached out of the Levant and crept round the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, from Greece to Sicily to Genoa. According to some, it had already taken hold of the port of Marseilles and the city of Aix and even Avignon, the seat of the Pope. His Holiness commanded penitential processions and prayers, to no avail. The citizens of that holy site fell as rapidly as the inhabitants of the most pagan places beyond Christendom.

The pestilence had not yet reached England and many comforted themselves with the notion that the sea would keep them safe. Or they believed that God would not permit them to be afflicted precisely because they were English. (After all, hadnt He provided them with a great victory over the French at the battle of Crcy less than two years before?) But the better informed or the more hard-headed knew it was only a matter of time before the sickness reached their island shores. Indeed, as the spring of 1348 turned to summer there were rumours that the infection had already taken hold at the ports in the far west of the country.

And when it did arrive at the place where you lived what then?

Neither prayers nor practical measures had any effect. You might bar the gates of your town and turn visitors away, but the pestilence, in all its cunning, found ways to circumvent every precaution. It was said that people could contract it merely from the glance of an infected victim. Some who had been nowhere near any sufferer fell sick nevertheless and died. And how they died!

Death took two equally dreadful forms. In this it might be likened to a pitchfork, for though you might avoid being impaled on one of its prongs you would most surely find yourself squirming on the other. Many vomited up copious quantities of blood from the lungs and died very soon afterwards. The rest endured fever and delirium before great swellings erupted in their necks or armpits or groins; after several agonising days they too perished.

If death by pestilence was like being impaled on a pitchfork, the question was: who was wielding it? Everyone knew that this familiar implement was one of the tools of the demons in Hell. Now it seemed as though the Devil himself were ranging across the earth, twitching his tail and flailing about with his pitchfork. More thoughtful, religious individuals were aware that such things happened only with Gods permission. And since God was permitting His people to be punished with these terrible forms of death, then it could only be because they had committed terrible sins, and then committed them again and again. Deep-dyed in wickedness. they rejected with laughter or contempt every opportunity for repentance provided by a generous, forgiving God.

If some individual had the temerity to ask whether all the citizens of Genoa or Aix or Avignon down to the last man, woman and child had committed sins deserving such terrible punishment, the answer given by the thoughtful and religious was that Gods purposes were inscrutable.

The only recourse for those English waiting in fear for the pestilence was to pray more earnestly and live yet more devoutly. Of course, not everyone was pious. Some carried on as usual, either because they were resigned to events or because they believed themselves to be Gods favourites and immune on that account. A surprisingly large number decided that, if the end was really coming, they might as well enjoy themselves and blotted out their remaining days on earth by drinking and gambling and whoring.

And then there were those who hoped that Gods wrath might be averted by going on a pilgrimage. Even had they the leisure and means, there was no question of travelling overseas; for example, to the holy cities of Jerusalem or Rome. So it was fortunate that there were shrines and sacred places closer to hand.

Not far from the north coast of Norfolk stood a famous shrine to Our Lady. Inside the priory at Walsingham was a chapel that sheltered an image of the Virgin and the Holy Child. The light of many candles was reflected in the offerings of gold, silver and jewels that bedecked the image. Though made only of wood, she was capable of working miracles. Everyone knew that prayers at Walsingham were especially efficacious, for the shrine possessed relics beyond compare, such as the Virgins milk preserved in a phial on the high altar of the priory church, or a finger joint belonging to St Peter. The Virgin herself had commanded a healing spring to flow forth near the chapel. It was not only ordinary folk who journeyed to pay their respects there; it was often visited by Edward III and the kings of England before him. If there was any single shrine in England that might be propitious for those hoping to ward off the pestilence, then it was surely Walsingham.

So it was that, in the spring and summer of 1348, streams of people made their way from all over England to this sacred site. Most made careful preparations before embarking on their pilgrimage to ensure their families and homes, their farms and other businesses were in good hands. In return, they promised to pray for those left behind and to bring back some protective token. Routes had to be planned and stopping-places decided in advance; the devotion of the pilgrims would be increased if due reverence was paid at the churches and lesser shrines on the way to Walsingham. There were even a few, particularly among those dwelling not far from the shrine, who declared they would walk the entire distance on bare feet.

If you could view these pilgrim parties from high above, you would see them moving along different tracks with a single-minded discipline and shared sense of purpose, moving like currents of water until they converged in larger streams and then in still larger ones before turning into a river that, flowing in from the south, overwhelmed the little town of Walsingham.

Next page