Clifford Harper. London, January 2013

The bicycle is half way between the shoe and the car, and its hybrid nature sets its rider on the margins of all possible surveillance. Its lightness allows the rider to sail past pedestrian eyes and be overlooked by motorized travellers. The cyclist, thus, possesses an extraordinary freedom: invisibility.

Valeria Luiselli, Manifesto Velo

A few years ago, after finishing a degree, I was looking for a new job. Id tried many: private tutor, mercenary essay-writer for the rich and lazy, barman, gardener, marketing consultant. Three months as a runner at a TV production company were enough of a taste of office life. Days spent tea caddying, photocopying and washing up left me cold. I couldnt drive, and my bosses told me I needed to learn if I wanted to get ahead in television. I arrived early and left late. Men carrying clipboards with radios strapped to their waists often shouted at me. I couldnt work the telephone system. I spent my afternoons shredding endless scripts on a temperamental shredder.

The only part of the job I did enjoy was the daily run to the edit suites in Soho, over the river from where I worked, carrying the days rushes heavy blue tapes sheathed in their grey plastic wallets; volatile nitrate film adorned with no smoking signs and warning skulls and crossbones; hard drives stuffed with data which I did by bicycle. Soon Id volunteer for any job taking me outside the office and across London, the further the better. Going to the archival warehouse to dig out old tapes or embarking on treks across the city for some specific prop became absurdly exhilarating. It was the solitude I valued, the freedom of the outside, the sounds and smells of the street. Soon I gave up my TV job and became a bicycle courier.

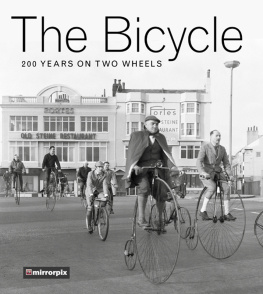

Id grown up in London and had always loved to cycle. My Dutch mother and car-phobic father ensured I learned to ride a bike almost as soon as I could walk. Theyd push me along the road by the scruff of my neck, riding beside me and steering me through gaps and around potholes with the delicate touch of puppeteers. The earliest bike I remember cycling under my own steam was a war-era, single speed machine with an iron frame and crumbling rubber grips. It was a faithful conspirator in my early explorations of the local territory. Together we built up our own map of the area noting the location of a chipped kerbstone that allowed us effortlessly to ramp up onto the pavement; the green car, always parked in the same spot, which shielded our turn from oncoming traffic charting features that felt as permanent as the roads we travelled over and the buildings we passed on our rounds.

When I became a bicycle courier I found that I loved cycling for my living. I loved the exhilaration of pedalling quickly through the city, flowing between stationary cars or weaving through the lines of moving traffic. I loved the mindlessness of the job, the absolute focus on the body in movement, the absence of office politics and cubicle-induced anxiety. I loved the blissful, annihilating exhaustion at the end of a days work, the dead sleep haunted only by memories of the bicycle. By night I dreamt of half-remembered topographies, each point-to-point run connecting in an ever-expanding series. Sensations of falling were transformed into forward motion. Hypnogogic jerks, those juddery twitches that occur on the edges of deep sleep, were smoothed out into circular pedal-strokes of the legs.

Most of all I loved learning what London taxi drivers call the Knowledge: the intimate litany of street-names and business addresses that constitutes a private map of the city, parallel to that contained within the AZ but written on the brain, read by leg and eye. After a while the trade routes became entrenched. By bike a new and unfamiliar London unveiled itself, a London dominated by road surfaces and traffic, a London composed of loading bays and stand-by spots, characterised by a sense of movement and flow. As a cyclist you inhabit the gaps between traffic, and as a courier you profit from what Jonathan Raban calls, in Soft City, the slack in the metropolitan economy. The job allows you access to a subterranean world of cavernous loading bays and car parks burrowed away underground. Its the iceberg theory of architecture. Another city exists alongside the London most people know, and cycle couriers are privy to this backstage city, with its post rooms manned by neon-tabarded security guards, its goods lifts, its secret, parallel infrastructures.

Big commercial buildings can feel like miniature city-states, and to a cycle courier the conflict between public and private, between the rules of the road and those of corporate estates, is constantly apparent. The glee with which the police hunt down and fine couriers who jump red lights (while letting off their commuting counterparts) is well known. But the guardians of private land are just as intolerant. In the biggest developments access for couriers is restricted to the cargo bays. Hulking ramps and doors must be navigated, pictures are taken, ID cards printed off stating your name, company, purpose, and privileges.

Sometimes, proclamations of ownership are local and specific, as in the small Polite Notices, which read as anything but, informing you that Bicycles locked to these railings will be removed. Elsewhere the limits of ownership spill out beyond the railings. Representatives of the West End Company patrol Oxford Street in red hats, giving tourists directions and admonishing cyclists who ride on the pavements. Some large commercial estates, such as Devonshire Square off Bishopsgate in EC2, have their own private police force. Anyone who isnt obviously an office worker, snatching a lunchtime sandwich in the open air, is moved on. Running is forbidden.

I worked as a bicycle courier for three years, on and off, as I bided my time in between stretches back at university and tried to work out what to do with my life. I loved every moment of it. Or perhaps love is the wrong word. For after a while on the bike, doing this work, you simply