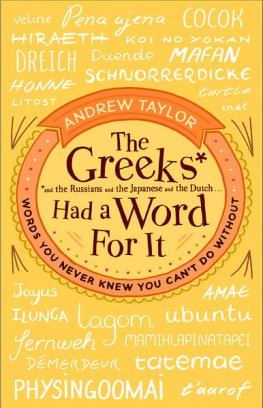

Do you ever search in vain for exactly the right word? Perhaps you wantto articulate the vague desire to be far away? Or you cant quite conveythat odd urge to go outside and check to see if anyone is coming? Maybeyoure struggling to say theres just the right amount of something not too much, but not too little? While the English may not have a wordfor it, the good news is that the Greeks, the Norwegians, the Dutch orpossibly the Inuit probably do.

Whether its mafan (a Mandarin word for when you just cant bebothered) or the Indonesian jayus (a joke so poorly told and sounfunny that you cant help but laugh), this delightful smorgasbord ofwonderful words from around the world will come to your rescue when theEnglish language fails. Part glossary, part amusing musings, but whollyenlightening and entertaining, The Greeks Had a Word For It meansyoull never again be lost for just the right word.

For Sam, Abi and Rebecca,

and Lucy, Sophie and Tom

Words are among the most important things in our lives somewhere justbehind air, water and food. For a start, theyre the way we pass on ourthoughts from one to another and from generation to generation. Withoutwords, its hard to see how mankind could ever have evolved fromape-like creatures grunting at the entrance to a cave and wonderingwhere they were going to find their next meal.

But words do more than that. They help us define our emotions, ourexperiences and the things we see. Put a name to something and you havestarted out on the road to understanding it.

To look at the figures, youd think that we already have more thanenough words in English estimates vary between five hundred thousandand just over two million, depending on how you count them. And mosteducated people use no more than twenty thousand words or so, whichmeans that we ought to have plenty to spare. Yet weve all had thosemoments when we want to say something and we cant find exactly theright one. Words are like happy memories you can never have enoughof them in your head.

And, maybe most important of all in these days of global interaction,when we need to understand each other more than ever before, words saysomething about us. If people need a word for a particular feeling, oraction, or experience, it suggests that they find it important in theirlives the Australian Aboriginals, for instance, have a word thatconveys a sense of intense listening, of contemplation, of feeling atone with history and with creation. In Spanish, theres a word forrunning ones fingers through a lovers hair, and in French one for thesense of excitement and possibility that you may feel when you findyourself in an unfamiliar place.

Words bring us together. Theyre precious. And if theyre sometimes veryfunny, too well, how good is that?

Physingoomai

(Ancient Greek)

Traditionally, sexual excitement as a result of eating garlic; but in amodern sense, the use of inappropriate adornments to enhance sexualattraction

THERE ARE SOME foreign words the English language clearly needs thecase for them is so obvious that it hardly needs to be put. Othersrequire a little more advocacy on their behalf. Take, for example, theAncient Greek word physingoomai (fiz-in-goo-OH-mie).

It refers to someone who gets over-confident and sexually excited as aresult of eating garlic. Fighting cocks were frequently fed garlic andonions before a bout because the Greeks and later cockfightaficionados believed that it would make the birds fiercer. The idea isthat if men were to follow the example of the fighting cocks and gorgeon garlic before going on a date, there would be no holding them back.

Whether or not garlic makes men horny, it certainly makes them smellyand thus less pleasant to be close to. As a result, even in these dayswhen programmes about cooking are all over the television and whenpeople seem more than happy to talk publicly about their sexualpreferences, it seems unlikely that it is a word that is going to beused frequently outside the rather restricted world of cockfighting.Even the Ancient Greeks dont seem to have required it all that often,since the word itself appears only once in the entire canon of Greekliterature, referring to some soldiers from the town of Megara in acomedy by Aristophanes.

In the play, however excited the soldiers get, its apparent that theyare going to have serious difficulties persuading any self-respectingAncient Greek girls to kiss their garlic-reeking lips. The remedy theyhave sought to increase their sexual potency at the same time greatlyreduces their ability to take advantage of it.

And there lies the clue to why physingoomai would be such a usefulterm in English. Young men who douse themselves in the sort of cheapaftershave that strips the lining from your nasal passages at firstwhiff; middle-aged men wearing blue jeans so tightly belted around wheretheir waist used to be that their bellies sag opulently over the top;women of a certain age wearing clothes that would have been daring ontheir daughters they are all, if they only knew it, falling into thesame trap as the Megaran soldiers.

The adornments they have chosen to boost their confidence and make themmore attractive to potential partners are exactly the things that willput those partners off. Cheap aftershave, tight belts and saggingbellies, and clothes that have been clearly stolen from your daughterswardrobe can be as effective as a garlic overdose in keeping people atarms length. Instead of whatever it was they were hoping for, those whorely on them to enhance their sexual appeal are likely to suffer what wemight call a physingoomai experience. And there are few morephysingoomai experiences than showing off by using long words to tryto impress someone. Just talking about physingoomai could lead to themost humiliating physingoomai experience of all.

Cafun

(Brazilian Portuguese)

Closeness between two people for example, to run ones fingerstenderly through someones hair

Think for a moment of the gentleness of affection. It needs a tone and alanguage of its own not the urgent, demanding words of love andpassion, but gentle, undemanding affection, the sort of love that asksfor nothing. It is often so diffident and unassuming that it maysometimes seem to take itself although never its object for granted.It may be the warm, safe, family feeling between a mother or father andtheir child, or the love of grandparents for their grandchildren;perhaps it is the closeness between two people that may some day turninto love, or it may be the relaxed fondness that remains when the fireof a passionate affair has burned low. Either way, it demands its ownexpression.

In Brazil, they have a phrase that works fazer cafun em algummeans to show affection of exactly that sort. More precisely, cafun(caf-OO-neh) often describes the act of running ones fingersthrough somebodys hair possibly lulling them to sleep, or possiblysimply expressing a drowsy fellow-feeling. Between two lovers, it mightcontain the gentlest hint of a sexual promise, precisely capturing thetender longing of the early days of a couples time together.

At other times, though, the word may be translated simply asaffection. Many Brazilians say they are seized by a melancholynostalgia when they are away from their home and thinking of theirfamily, their religion and their memories. They miss their mothersrabanada, a sort of French toast topped with sugar, cinnamon andchocolate that is traditionally served at Christmas; their auntsbacalhoada, or salted cod stew; and their grandmas cafun.

Its not a particularly sentimental word in itself. Some authoritiessuggest that the gesture originated in a mothers gentle search throughher childrens hair for fleas and lice, and if that thought isnt enoughto quell any incipient sentimentality, its sometimes accompanied by theclicking of the fingernails to mimic the cracking of occasional nits.Theres still plenty of affection in the gesture like two chimpanzeesgently grooming each other though the click of lices eggs beingdestroyed is not necessarily a sound you would wish to reproduce on aValentines Day card, even if you could.