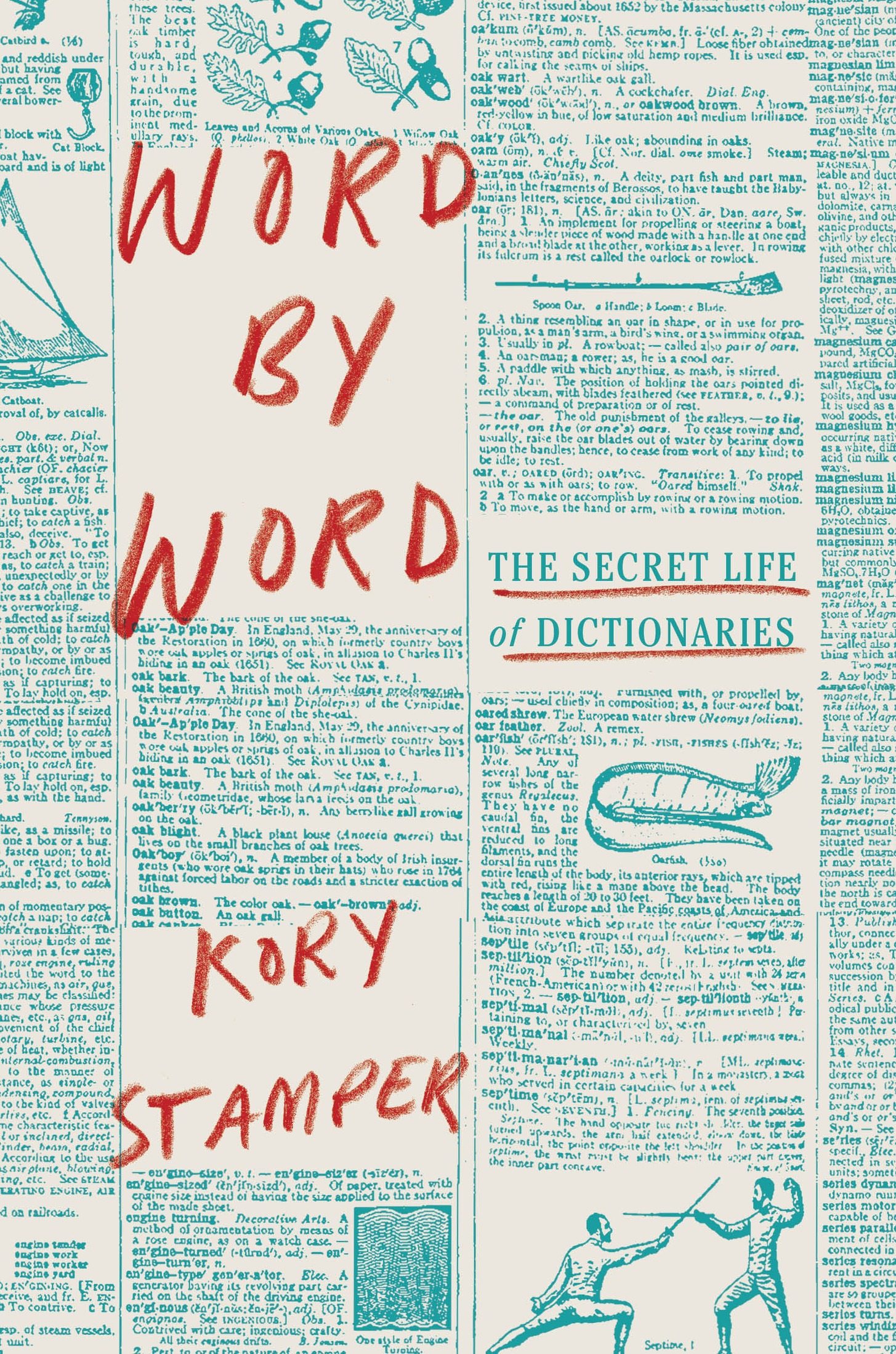

Copyright 2017 by Kory Stamper

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

Pantheon Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Owing to space limitations, permissions acknowledgments may be found following the index.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Name: Stamper, Kory, author.

Title: Word by word : the secret life of dictionaries / Kory Stamper.

Description: New York : Pantheon Books, [2017]. Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016024253 (print). LCCN 2016037824 (ebook). ISBN 9781101870945 (hardcover). ISBN 9781101870952 (ebook).

Subjects: LCSH : LexicographyHistory. Encyclopedias and dictionariesHistory and criticism. LexicographersBiography. BISAC: REFERENCE / Dictionaries. BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Personal Memoirs.

Classification: LCC P 327. S 695 2017 (print). LCC P 327 (ebook). DDC 413.028dc23. LC record available at lccn.loc.gov/2016024253

Ebook ISBN9781101870952

www.pantheonbooks.com

Cover design by Oliver Munday

v4.1_r1

ep

Contents

FOR MY PARENTS, ALLEN AND DIANE, WHO BOUGHT ME BOOKS AND LOVED ME WELL.

It may be observed that the English language is not a system of logic, that its vocabulary has not developed in correlation with generations of straight thinkers, that we cannot impose upon it something preconceived as an ideal of scientific method and expect to come out with anything more systematic and more clarifying than what we start with: what we start with is an inchoate heterogeneous conglomerate that retains the indestructible bones of innumerable tries at orderly communication, and our definitions as a body are bound to reflect this situation.

PHILIP BABCOCK GOVE, Merriam-Webster in-house Defining Techniques memo, May 22, 1958

Preface

L anguage is one of the few common experiences humanity has. Not all of us can walk; not all of us can sing; not all of us like pickles. But we all have an inborn desire to communicate why we cant walk or sing or stomach pickles. To do that, we use our language, a vast index of words and their meanings weve acquired, like linguistic hoarders, throughout our lives. We eventually come to a place where we can look another person in the eye and say, or write, or sign, I dont do pickles.

The problem comes when the other person responds, What do you mean by do, exactly?

What do you mean? Its probable that humanity has been defining in one way or another since we first showed up on the scene. We see it in children today as they acquire their native language: it begins with someones explaining the universe around them to a rubbery blob of drooling baby, then progresses to that blob understanding the connection between the sound coming out of Mamas or Papas mouthcupand the thing Mama or Papa is pointing to. Watching the connection happen is like watching nuclear fission in miniature: there is a flash behind the eyes, a bunch of synapses all firing at once, and then a lot of frantic pointing and data collection. The baby points; an obliging adult responds with the word that represents that object. And so we begin to define.

As we grow, we grind words into finer grist. We learn to pair the word cat with meow; we learn that lions and leopards are also called cats, though they have as much in common with your long-haired Persian house cat as a teddy bear has with a grizzly bear. We set up a little mental index card that lists all the things that come to mind when someone says the word cat, and then when we learn that in parts of Ireland bad weather is called cat, our eyes widen and we start stapling little slips of addenda to that card.

At heart, we are always looking for that one statement that captures the ineffable, universal catness represented by the word cat, the thing that encompasses the lion cat and the domestic-lazybones cat and the bad weather in Ireland, too. And so we turn to the one place where that statement is most likely to be found: the dictionary.

We read the definitions given there with little thought about how they actually make it onto the page. Yet every part of a dictionary definition is crafted by a person sitting in an office, their eyes squeezed shut as they consider how best to describe, concisely and accurately, that weather meaning of the word cat. These people expend enormous amounts of mental energy, day in and day out, to find just the right words to describe ineffable, wringing every word out of their sodden brains in the hopes that the perfect words will drip to the desk. They must ignore the puddle of useless words accumulating around their feet and seeping into their shoes.

In the process of learning how to write a dictionary, lexicographers must face the Escher-esque logic of English and its speakers. What appears to be a straightforward word ends up being a linguistic fun house of doors that open into air and staircases that lead to nowhere. Peoples deeply held convictions about language catch at your ankles; your own prejudices are the millstone around your neck. You toil onward with steady plodding, losing yourself to everything but the goal of capturing and documenting this language. Up is down, and the smallest words will be your downfall. Youd rather do nothing else.

We approach this raucous language the same way we approach our dictionary: word by word.

Throughout this book, I will be using the singular their in place of the gender-neutral his or the awkward his or her when the gender of the referent isnt known. I know some people think this is controversial, but this usage goes back to the fourteenth century. Better writers than I have used the singular their or they, and the language has not yet fallen all to hell.

upadvb (1) : to a state of completeness or finality (MWU; see the bibliography for more details)

downadvd : to completion (MWU)

badadjslanga : GOOD, GREAT (MWC11)

Hrafnkell

On Falling in Love

W e are in an uncomfortably small conference room. It is a cool June day, and though I am sitting stock-still on a corporate chair in heavy air-conditioning, I am sweating heavily through my dress. This is what I do in job interviews.

A month earlier, I had applied for a position at Merriam-Webster, Americas oldest dictionary company. The posting was for an editorial assistant, a bottom-of-the-barrel position, but I lit up like a penny arcade when I saw that the primary duty would be to write and edit English dictionaries. I cobbled together a rsum; I was invited to interview. I found the best interview outfit I could and applied extra antiperspirant (to no avail).

Steve Perrault, the man who sat opposite me, was (and still is) the director of defining at Merriam-Webster and the person I hoped would be my boss. He was very tall and very quiet, a sloucher like me, and seemed almost as shyly awkward as I was, even while he gave me a tour of the modest, nearly silent editorial floor. Apparently, neither of us enjoyed job interviews. I, however, was the only one perspiring lavishly.