Thank you for buying this ebook, published by Hachette Digital.

To receive special offers, bonus content, and news about our latest ebooks and apps, sign up for our newsletters.

For more about this book and author, visit Bookish.com.

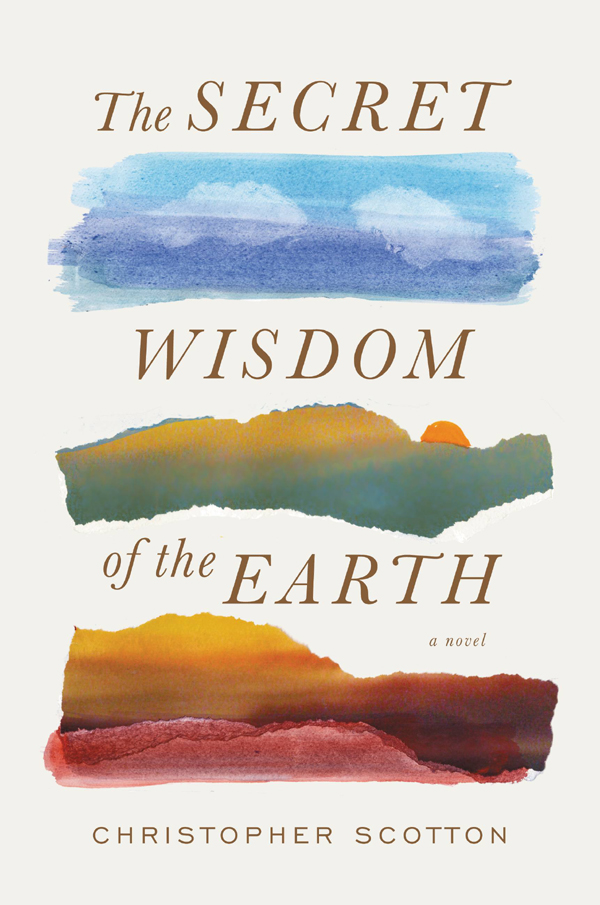

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

Copyright 2015 by Christopher Scotton

Cover illustrations by Donna Levinstone

Cover design by Anne Twomey

Cover copyright 2015 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitutes unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Grand Central Publishing

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

hachettebookgroup.com

twitter.com/grandcentralpub

First ebook edition: January 2015

Grand Central Publishing is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Grand Central Publishing name and logo is a trademark of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

ISBN 978-1-4555-5193-4

E3

For Michael on his fourteenth birthday and for Connor on his.

Sweet are the uses of adversity,

Which like the toad, ugly and venomous,

Wears yet a precious jewel in his head;

And this our life exempt from public haunt,

Finds tongues in trees, books in the running brooks,

Sermons in stones, and good in every thing.

I would not change it.

William Shakespeare

It was always coal.

Coal filled their pantry and put a sense of purpose in their Monday coffee. Coal was Christmas and the long weekend in Nashville when the Opry offered half-price tickets. Coal was new corduroy slacks and the washboard symphony they played to every step. Coal was a twice-a-month haircut. Coal was a store-bought dress and the excuse to wear it. Coal took them in as teenagers, proud, cocksure, and gave them back fully played out. Withered and silent.

Coal was the double-wide trailer at twenty and the new truck. Coal was the house with the front porch at twenty-eight and the satellite dish. Coal was the bass boat at thirty-five and the fishing cabin at forty.

And then, after they gave their years to the weak light and black sweat, coal killed them.

And began again.

T he Appalachian Mountains rise a darker blue on the washed horizon if youre driving east from Indiana in the morning. The green hills of the piedmont brace the wooded peaks like sandbags against a rising tide. The first settlers were hunters, trappers, and then farmers when the game went west. In between the hills and mountains are long, narrow hollows where farmers and cattle scratch a living with equal frustration. And under them, from the Tug Fork to the Clinch Valley, a thick plate of the purest bituminous coal on the Eastern Seaboard.

June was midway to my fifteenth birthday and I remember the miles between Redhill, Indiana, and Medgar, Kentucky, rolling past the station wagon window on an interminable canvas of cornfields and cow pastures, petty towns and irrelevant truck stops. I remember watching my mother from the backseat as she stared at the telephone poles flishing past us, the reflection of the white highway line in the window strobing her haggard face. It had been two months since my brother, Joshua, was killed, and the invulnerability I had felt as a teenager was only a curl of memory. Mom had folded into herself on the way back from the hospital and had barely spoken since. My father emerged from silent disbelief and was diligently weaving his anger into a smothering blanket for everyone he touched, especially me. My life then was an inventory of eggshells and expectations unmet.

Pops, my maternal grandfather, suggested Mom and I spend the summer with him in the hope that memories of her own invulnerable childhood would help her heal. It was one of the few decisions on which my father and grandfather had ever agreed.

The town was positioned in a narrow valley between three sizable mountains and innumerable hills and shelves and finger hollows that ribboned out from the valley floor like veins.

We had not visited Pops since Josh was born three years before, and as we came over the last hill, down into Medgar on that Saturday, the citizens stared at us like they were watching color TV for the first time. A fat woman in red stretch pants dragging a screaming child stopped suddenly; the child jounced into her back. Two men in eager discussion over an open car hood turned in silence, hands on hips. Booth four at Biddles Gas and Grub immediately discontinued their debate about proper planting cycles and launched wild speculation about the origin and destination of the blue station wagon with suitcases and a bike bundled onto the luggage rack. People just didnt move into eastern Kentucky back then.

Twenty-two Chisold Street sat straight and firm behind the faded white fence that aproned its quarter acre. The front porch was wide and friendly, with an old swing bench at one end, a green wicker sofa and chairs at the other. The house was a three-bedroom Southern Cape Cod with white pillars on the porch, double dormers jutting out of the roof like eyes. One broken blind closed in a perpetual wink. The yard was trim and perfect.

We drew up in the wagon, a thin smile on my mothers face for the first time in months. My father touched her arm gently to tell her she was home.

Pops had been vigiling on the wicker sofa, chewing the end of the long, straight pipe he never lit. He slapped both knees, bellowing an abundant laugh as he raced down the porch steps before the car was even at a full stop. He reached in the window to unlock the door, opened it as the engine cut off, and pulled Mom out of the front seat into a bracing hug. Its good to have you back home, Annie.

She nodded blankly and hugged back.