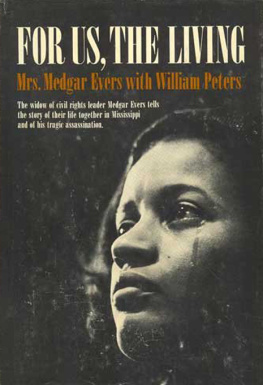

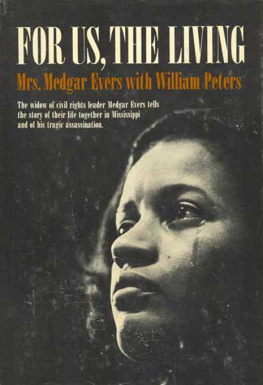

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 67-22454

Copyright 1967 by Myrlie B. Evers and William Peters

All Rights Reserved

Printed in the United States of America

For Darrell, Rena, and Van

Medgar Evers believed in his country; it now remains to be seen whether his country believes in him.

Roy Wilkins

June 19, 1963

Arlington, Virginia

... It is for us, the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before usthat from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion; that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain; that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom; and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Abraham Lincoln

November 19, 1863

Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

I

Somewhere in Mississippi lives the man who murdered my husband. Sometimes at night when my new house in Claremont, California, is quiet and the children are in bed I think about him and wonder how he feels. I have never seriously admitted the possibility that he has forgotten what I can never forget, though I suppose that hours and even days may go by without his thinking of it. Still, it must be there, the memory of it, like a giant stain in one part of his mind, ready to spring to life whenever he sees a Negro, whenever his hate rises like a bitterness in the throat. He cannot escape it completely.

And when that memory returns to him, I wonder if he is proud of what he did. Or if, sometimes, he feels at least a part of the enormous guilt he bears. For it is not just that he murdered a man. He murdered a very special manspecial to him, special to many others, not just special to me as any man is to his wife. And he killed him in a special way. He is not just a murderer. He is an assassin.

He lived in a different world from the one Medgar and I shared for eleven and a half years, though all three of us must have spent most of our lives within a few miles of each other. And those different worlds we inhabited had been there, side by side in Mississippi, all along. When they collided, finally, my husband lay dying outside the door of our home, his key clutched tightly in his hand, a trail of his blood bearing witness to his struggle to reach safety inside. And as his lifes blood poured out of him, his assassin dropped his weapon and slunk away through the underbrush of a vacant lot, hidden by the darkness of night. What were his feelings then? Joy? Fear? Triumph?

What are his feelings now?

I wonder if he has told others of his act that night, if, perhaps, he brags about it. And if he does, I wonder how those awful boasts are received. Do the other white men who hear his confession congratulate him? Do they laugh and slap him on the shoulder as though to share in his deed? Or do some, at least, stir uneasily at his tale? Do they, perhaps, even turn their backs on him, blotting him out, unwilling or unable to be a part of his murder even after it is done?

Much of the recent history of Mississippi could be told in the lives of these two men, my husband and his killer, the murdered and the murdererone dead but free, the other alive and at large but never really free: imprisoned by the hate and fear that imprison so many white Mississippians and make so many Negro Mississippians still their slaves. Medgar and his assassin shared not only a state but a time; they grew up and lived in the same years, subject to the same influences. They breathed the same air, may have even brushed shoulders on the street or in a store.

Surely they heard the same speeches about the question that was central to both of their lives and yet moved them in such profoundly different directions. And that, too, is a strange thought: that there were times when both men sat by radios or television sets hearing the same news, the same words spoken about the racial crisis in Mississippi. But, oh, what different thoughts they must have had!

Medgar used to astonish Northern reporters who asked why he stayed in Mississippi by answering simply that he loved Mississippi. He did. He loved it as a man loves his home, as a farmer loves the soil. It was part of him. He loved to hunt and fish, to roam the fields and woods. He loved the feeling that here there was space for him and his family to grow and breathe. He had visited many other places. He had served in the Army in England and France; he had worked summers in Chicago during his college years; but always he came back to Mississippi as a man coming home.

Chicago held no appeal for him; he called life there a rat race, and he was puzzled and a little resentful that all the Negroes from his part of Mississippi seemed to live in the same area of Chicagos South Sidethe same block, almost; often the same buildings. He would say with disgust that Negroes who left his home town of Decatur, Mississippi, for the North all ended in the same neighborhoods of either Chicago or Flint, Michigan. He didnt like the dependence that implied, and he didnt like the Negro ghettos either. Both offended his sense of freedom. Chicago to him was a place to work, a place where you could earn better wages. Mississippi, with all its faults, was a place to live.

Medgar, of all people, was not blind to Mississippis flaws, but he seemed convinced they could be corrected. He loved his state with hope and only rarely with despair. It was his hope that sustained him. It never left him. Despair came infrequently, and a day of hunting or fishing dispelled it. The love remained.

I suppose the man who killed Medgar loved Mississippi, too, in his twisted, tortured way. He must have loved the Mississippi that divides whites from Negroes, that by definition made him better than any Negro simply because he was white. In a way, I suppose, he was a jealous suitor, seeking by his murder to eliminate a rival, for he loved the Mississippi Medgar sought to change. What Medgar loved with hope, his assassin loved with fear. And he killed, I suspect, largely out of that fear.

But knowing this, thinking about it, wondering at it in the stillness of the night these many months after that act of horror cannot change the emptiness of life without my husband. There are times when I pause in a busy day and realize with surprise that I survive, that I am continuing, that my life goes on. For a long time after that shot rang out in the darkness and put an end to my life with Medgar, it seemed impossible to go on. And yet I do; the children eat and sleep and go to school, their lives almost complete; day follows night; and emptiness is, if not filled, at least ignored a little more each day than the day before.

But there are moments when it all comes back, when the warmth of those years with Medgar floods in on me, when I live again those shattering moments after the crack of the rifle. And then I wonder about the man who saw my husbands back in the sights of a high-powered rifle and coldly squeezed the trigger. What kind of man could that be? What kind of life brought him to that clump of bushes where he hid and waited? What can he be thinking now that the act is committed and he has escaped its legal consequences?

They are all questions I cannot answer in any sure or final sense. I can only speculate out of an intuitive knowledge of what hate can do to the human soul. For I, too, have been tempted to hate. It has been difficult, living in Mississippi, not to. Hate is one of the rare commodities whites and Negroes are permitted to share equally in that state. It is one of the few things in more than adequate supply for all.

Next page