Much appreciation to Lisa Drew, my editor and publisher at Scribner, and to my agents, Maureen and Eric Lasher, for their extraordinarily patient tutelage and guidance throughout my inaugural sojourn into the labyrinth of the publishing landscape.

Many thanks to Anne Stascavage, who also provided editing assistance. She proved exceptionally helpful, particularly on initial questions of tone.

Although their names are mentioned in the book, I wish to here express my gratitude to court reporter Kaye Kerr and Hinds County circuit clerk Barbara Dunn for going beyond the call of duty. Kaye not only provided court transcripts, but transcribed all witness interviews and grand jury testimony for me during the investigation. Barbara has always been of invaluable assistance in furnishing access to court documents and evidence.

Last, but not least, I thank my family for their continued love, support, and forbearance.

AUTHORS NOTEAND INTRODUCTION

This is the true and complete story of the most important and fascinating case I have tried during my twenty-plus years in the courtroom. I realized its special nature early in the investigation and began keeping a journal. Soon after the conclusion of the case, I decided to write a memoir drawing upon my journal, letters, newspaper articles, reports of the Jackson Police Department and FBI, court transcripts, taped interviews gathered during the investigation and trial, and my memory.

I initially intended to write a private memoir for my children so, after attaining the necessary maturity, they would know and fully understand everything that happened as well as my feelings and motivations along the way.

Through the friendship and encouragement of writer Willie Morris, I became convinced that I should share my story on a much larger scale. Although the thought of writing a book for publication was rather intimidating to me, Willie was relentless. You not only can do it, he urged, you must do it. Indeed, as noted by Edmund Bergler, the real writer is haunted by a plot which he must write out of inner necessity.

After three years of writing, I finished the final chapter during the last week of July 1999 and spoke to Willie by phone that evening. He shared my excitement, volunteered to write the introduction, and invited my wife, Peggy, and me to come over one night the following week to join him and his wife, JoAnne, to eat pizza and watch Judgment at Nuremberg on video. We would talk more about the introduction then, he said. It never happened. On Monday, August 2, 1999, Willies kind and generous heart stopped beating.

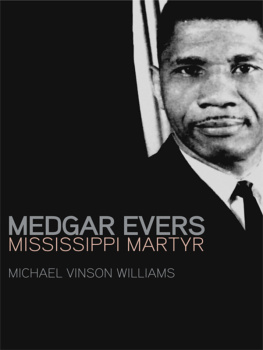

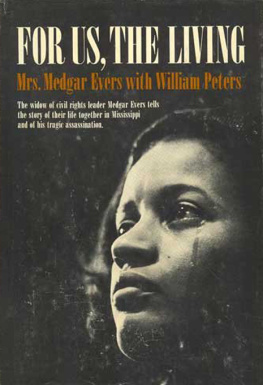

I would never presume to write that which Willie, another Faulkner, was to pen, nor could I bring myself to ask a substitute to fill the void. I know firsthand Willies feelings about this story. We discussed it many an evening over an equal number of bottles of Willies favorite merlot. An understanding was reached. Willie would write of the making of Ghosts ofMississippi, the Rob Reiner movie about the reinvestigation and reprosecution of white supremacist Byron De La Beckwith for the 1963 assassination of civil rights leader Medgar Evers, and indeed Willie did so in TheGhosts of Medgar Evers (Random House, 1998). I, on the other hand, would write the definitive and detailed account of the case itself.

Good friend and consummate writer that he was, Willie couldnt resist revealing his feelings about the case and me in his book. While unusual, it is only fitting that his words serve as a prelude to the journey to justice chronicled in the pages that follow:

In 1994 I was drawn to an extraordinary story. That year in Jackson, Mississippi, I covered for a national magazine the third and final trial of the radical white supremacist Byron De La Beckwith for the June 12, 1963, assassination of the thirty-seven-year-old Mississippi civil rights leader Medgar Evers, shot in the back in the driveway of his house.

The case against Byron De La Beckwith, one journalist wrote, was brought back not because of any one event, but by a confluence of many events in a slow tide of change. A younger generation of whites accepted integration, in part out of repulsion toward everything the Beckwiths had once stood for.

One of these younger whites was an assistant district attorney named Bobby DeLaughter, who would handle the new investigation against staggering odds and eventually at great personal and professional cost.

He is an introverted, complicated man and, as with Myrlie Evers, only reveals himself to people he really trusts. He is modestly self-confident and brave. He is deeply religious but does not advertise it. He is the long-distance runner. Yet beneath the often stoic facade there are intensely strong emotions, and also a strain of irrepressible humor, buttressed by a gift for telling stories.

Without Bobby DeLaughter, Beckwith would never have been convicted and in the years to come the country will need all the heroes and heroines it can get, no matter what their color.

The 1994 trial and the investigative work that led to it culminated one of the most unusual episodes of criminal prosecution in American history. It tells a story that stays with youa story about conscience. Bobby DeLaughter and Myrlie Evers: two who grew in conscience, courage, and trust. As a book lives or dies on its inherent life-giving truth and passion, this story, I believe, will endure.

If My people who are called by My name humble themselves, pray, seek My face, and turn from their wicked ways, then I will hear from Heaven, and will forgive their sin,... heal their land, [and] let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream, [for] the Lord of Hosts is exalted by justice.

2 Chronicles 7:14, Amos 5:24, and Isaiah 5:16 (NRSV)

PROLOGUE

T he murderer will be free? Could I have heard correctly? His conviction vacated, the jurys unanimous guilty verdict held for naught? Nationwide celebrations for justice will turn to cries of outrage. Salutes to a state that had long suffered a poor reputation for affording basic civil rights and humanity will evolve into I told you so; nothing has really changed in Mississippi in thirty years. I recall my Faulkner: The past is not dead; its not even past. My antagonists will relish running me out of town, and my dream of one day becoming a judge will probably remain just that: a dream.

Its Monday, December 22, 1997. I have just received word from a source that enough judges of the Mississippi Supreme Court have voted to overturn the conviction of Byron De La Beckwith. The decision will be made public in a matter of hours.